Trieste’s World-Famous Community Mental Health Program Under Attack

A program that was a living symbol of the movement for dignity of mental patients was giving power to an official who was criticized for his treatment methods.

When Pierfranco Trincas took up his job as the director of the Barcola mental health center in Trieste, Italy, he took center stage in a battle over the future of a mental health system praised by the World Health Organization and admired around the globe.

The appointment of Trincas on August 1 set alarm bells ringing among supporters of Trieste’s unique system of community mental health, developed in the 1970s by psychiatrist Franco Basaglia, who led a revolution from within against the city’s brutal mental asylum and created a new model to replace it.

Suddenly, it seemed, a program that was a living symbol of the movement for dignity of mental patients and against their routine abuse was giving power to an official who just two years ago was running a psychiatric hospital criticized in official reports for its use of physical restraints and forced treatments.

To many who have been involved in Trieste’s community-based system, it suggested a direct attack on the legacy of Basaglia, whose reforms led to national legislation mandating community care and limiting the size of psychiatric hospitals and drew international attention to Trieste.

“A system that works is being dismantled because of an ideological prejudice,” said Roberto Mezzina, a psychiatrist and former director of mental health in Trieste. “This is a space that was always independent and dedicated honestly to the service of the population.”

Last week, Mezzina said, the Friuli Venezia-Giulia region approved new guidelines for management of the health system, eliminating one of Trieste’s four mental health centers and reducing the hours for which the others remain open to the public.

“Mental health is being merged with substance abuse in a single department and the health districts are being reduced in number and complexity,” said Mezzina. “What we feared is happening now.”

Mezzina fears the program has been targeted for political reasons by the hard-right regional government in the northeastern Friuli-Venezia Giulia region, run since 2018 by a right-wing coalition dominated by the anti-immigrant League party.

A 2019 inspection of two mental health centers attached to Cagliari’s Santissima Trinità Hospital, both of which were run by Trincas, raised concerns over the use of physical restraints and the environment in which patients were held.

Mauro Palma, Italy’s national ombudsman for the rights of people deprived of their liberty, found the two Cagliari centers had no educators or social workers on their staff, and one of them had failed to keep an accurate record of patients subject to obligatory mental health treatment. One of Trincas’ centers had no outside area available for use by its patients and the second had a neglected outdoor space, “with no protection from the sun and rain and infested with mosquitoes.”

Palma’s office is responsible for inspecting prisons, police cells and migrant detention centers as well as mental health facilities. The inspections in Sardinia were carried out by five members of his staff and two consultants.

HIs report found that a second doctor’s opinion, required by law to validate obligatory treatment, was often provided by a member of the center’s staff and was therefore not independent. Among the cases not properly recorded in the hospital’s register was that of A.P., a patient who died at the end of 2018 “after seven days of restraint and alleged mistreatment.”

In an interview with La Repubblica before taking up his new post, Trincas said he had assumed control of one of the centers just a few months before the inspection and in the other had made minimal use of physical restraint. “No one wants to reopen the lunatic asylums or limit the freedom of the individual,” he told the paper. “I have been treated as a torturer worthy of (the Nazi prison camp doctor Josef) Mengele.”

Riccardo Riccardi, the regional health minister and a member of Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party, did not reply to a request for comment. He has denied having any intention of undermining Trieste.

Gisella Trincas, president of Unasam, a national network of mental health associations and no relation of the Sardinian psychiatrist chosen to run the Barcola center, said her organization, and families of mental health patients in Trieste, were worried when Trincas’ candidacy emerged.

“Trincas is a charming man, who comes from Cagliari, where I live, and where the approach to mental health is one of locked doors and physical restraint,” the Unasam president said. “He has rejected the community approach to mental health that we support, which involves small, local mental health centres accessible 24/7.”

Gisealla Trincas said she feared her namesake was part of a political project to rein in the Trieste model. “If the Trieste model collapses we can forget about extending the Basaglia reforms to the rest of our national territory,” she said.

Trincas said she was concerned about the selection process that led to the Sardinian psychiatrist’s appointment. “There was something murky about it. His score based on his curriculum was low, but it shot up after the oral part of the process, which was conducted behind closed doors.”

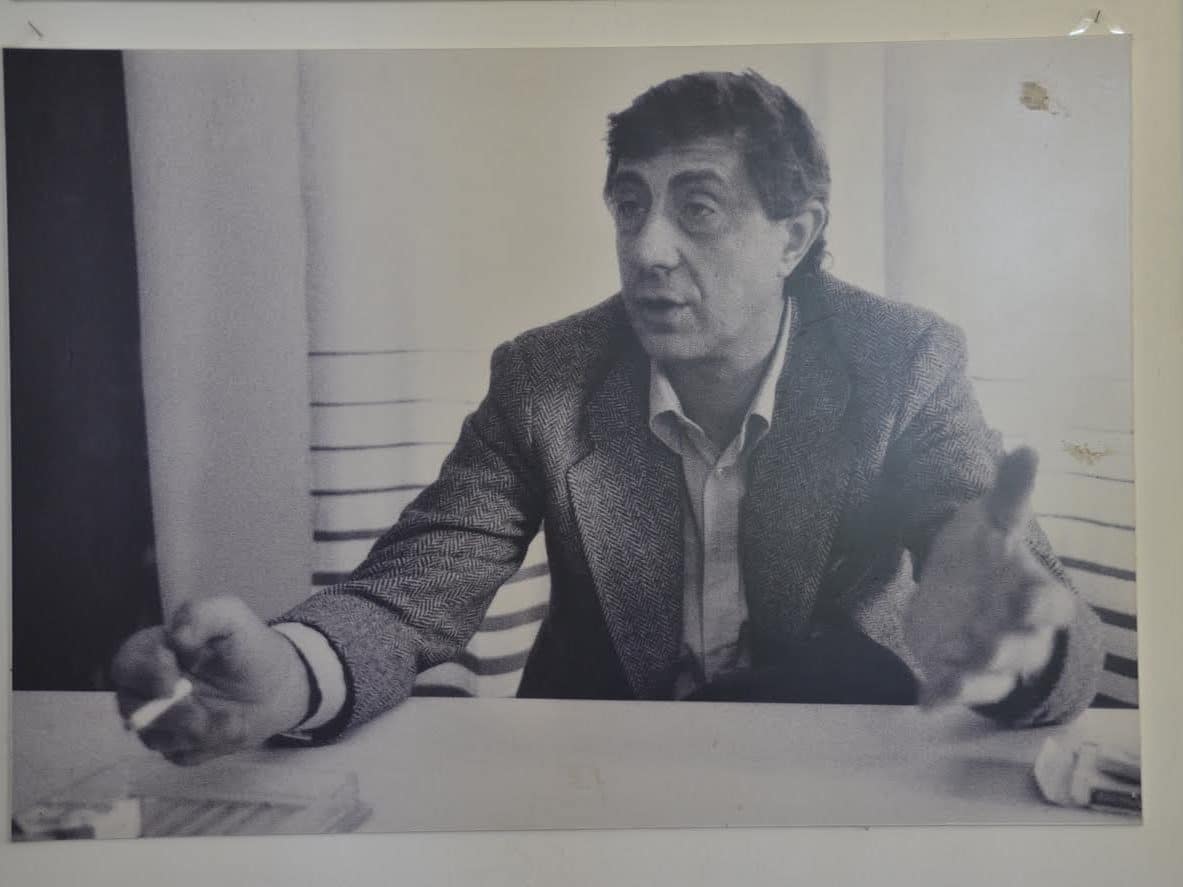

Peppe Dell’Acqua, a former director of the Barcola center and a partner of Basaglia in the Trieste area mental health reforms, said he was “sincerely worried and intimately pained by what is happening,” he said. “There is a ferocity and unreasonableness about it that is really inexplicable.”

Basaglia’s battle to restore basic rights to people suffering from mental illness challenged the psychiatric establishment of the day and helped shift relationships between powerful doctors and passive patients.

Dell’Acqua said a positive approach to mental health stressed the relationships and desires of patients and avoided defining anyone as permanently mad. “The mentally ill person is a citizen like everyone else,” he said. “That was Basaglia’s great victory.”

Dell’Acqua remains optimistic however. “Italian democracy is living through a negative period,” he said. “The roots of the Trieste system are strong. I think they will survive.”

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.