Librarians’ Mental Health Threatened By Book Bans, Abuse And Harassment

Some librarians used to make jokes about Fahrenheit 451 as they pushed back on threats of censorship. But now it hits too close to home.

Martha Hickson, a librarian at North Hunterdon High School in Annandale, New Jersey, has long enjoyed “kibbitzing” with the teens in her school and overseeing its bustling library. Even before classes start, students meet there, look for books that pique their interest, work on crafts, play board games “or just chill,” says Hickson, who has worked there for 17 years. She traded in a corporate job for this one because, she says, she wanted to make a difference. But last year, in late September, Hickson’s world was upended.

At a school board meeting on September 28, a parent got up and likened Hickson and the school board members to “sex offenders” for making available two award-winning books on her school’s shelves, one entitled Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe, a memoir about gender identity, and Lawn Boy by Jonathan Evison, a semi-autobiographical book that recounts the experiences of a Mexican American youth dabbling in romantic and sexual exploration with a fellow classmate.

“In my opinion, sex offenders and/or perpetrators have no place in or near our schools,” railed one parent. “Those responsible should be required to step down, be investigated and charged accordingly.” Watching the meeting, Hickson said she was “stunned” by the charges, but most disheartened by the lack of response by school board members, who “sat there and said and did nothing.”

Then things ramped up. “Administrators in the building were actively antagonistic and accusatory toward me, as if I had actually committed some sort of crime just by doing my job,” she said. Some school staff shunned her. Then came the hate mail and a barrage of social media attacks. “I was called disgusting, truly sick. There were accusations made that I was a pornographer, a pedophile, that I was grooming children” – charges that left her reeling with shock and disbelief.

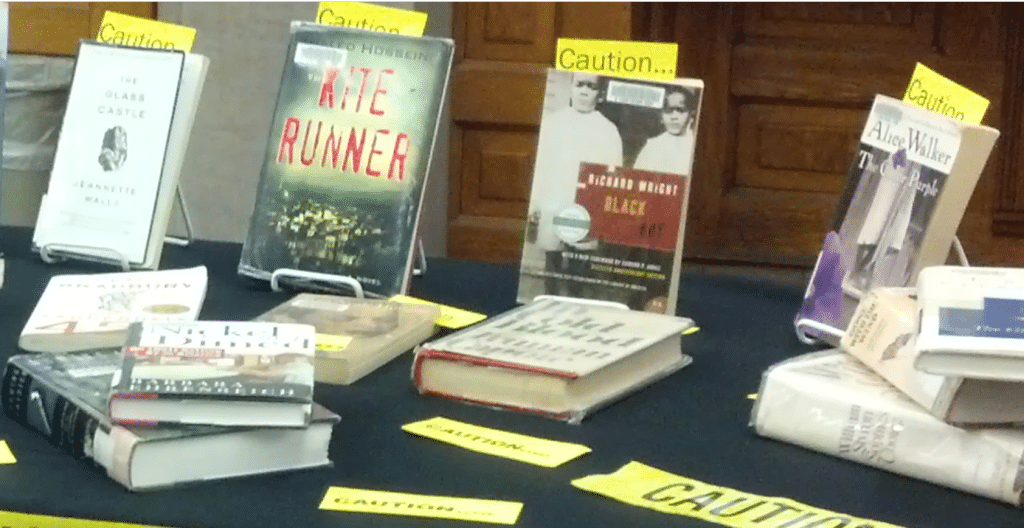

Similar attacks playing out in school districts across the country are causing deep distress, anguish and anxiety among librarians. Attempts to censor books – everything from biographies of Martin Luther King Jr. to LGBTQ-themed books to Maus, a graphic novel about the Holocaust – spiked from 156 in 2020 to an “unprecedented” 330 in just 3 months in 2021, according to Kristin Pekoll, assistant director of the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom. For trying to prevent such censorship, many librarians have been cyber-bullied, threatened and doxxed, slang for having their address or other private information displayed online. Every week Pekoll spends time listening to and soothing 15 to 20 librarians around the country who are on the brink.

For carrying books in their libraries about different gender identities and adolescence, “they’re getting accused of horrifying, horrible acts of grooming children, pedophilia, promoting pornography,” Pekoll said. “They’re having people call the cops on them and saying they’re not fit to deal with children. They’re losing their jobs, and they’re being demoted. And it’s just really hard for a lot of them right now. There’s very low morale. There’s a lot of fear.”

For Hickson, the emails and social media attacks cut deep, as did news reports of threats and harassment against librarians across the country. “I was afraid because (of) the level of anger in those messages,” she recalled. “I started to fear for my safety at work and at home.”

Things took a turn for the worse one day in late October. Hickson was juggling her usual job responsibilities while responding to new ones: the need to answer her own personal hate mail, field a public record request from a parent on the acquisition histories of challenged books, and give feedback to worried students in the Gay/Straight Alliance about their strategies for combating attacks. Suddenly she felt her heart racing.

“I started to fear for my safety at work and at home.”

Martha hickson, a school librarian in annandale, New Jersey, on social media threats

She went to the school nurse’s office, and her blood pressure was dangerously high. “I became very emotional,” she remembers. “I had trouble speaking. I had trouble containing my emotions. I was crying, and they called my husband to come and pick me up,” she said. Hickson’s doctor put her on medical leave.

‘A politically coordinated attack’

To Nora Pelizzari of the National Coalition Against Censorship, what’s happening in schools this past year is notably different than in previous years. “What we’re seeing is not just an elevated number of book challenges,” she said. “What we’re seeing is very clearly a politically coordinated attack on what ideas are allowed to be accessed in schools, what students are allowed to choose to read, and how teachers are allowed to address various topics and subjects.”

Dozens of pieces of legislation promoting censorship in schools have been introduced around the country, says Pelizzari, and they’re written in vague language “with the intention of chilling speech, of making teachers or librarians afraid of running afoul of these poorly defined statutes with the idea that they will avoid these topics entirely.”

In Texas, Governor Greg Abbott told education officials in a letter that having “pornographic” material such as the book Gender Queer in Texas schools, is against the law. One librarian in Texas – we’ll call her Marian – fears retaliation, and apparently with good reason. A local Facebook group supporting book challenges posted the address of a local librarian on its Facebook page. “At that point, several of us felt we needed to add security to our own homes, so I added external cameras to my house,” Marian said in an interview “And we added a security system.”

Then Marian herself was targeted. Last August, her photo was featured with the caption “Another heretical liberal librarian” on the group’s Facebook page.

Marian believes she was targeted because of her work sponsoring a student-led anti-racism coalition. Her mental health plummeted. She began having panic attacks and felt too threatened to go places in her own neighborhood. “It felt so violent, and the nature of their posts were so angry and hateful,” she said. “I avoided shopping in the community. I would go out of my way in another direction to go to a Target that was far away. My biggest fear was that I would be somewhere with my kids, and someone would recognize me and confront me in front of them.”

When the harassment first began, Marian and fellow librarians would try for levity and responded to book challenges by sharing quotes from the dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451, in which all books are outlawed and burned whenever they are found. (Fahrenheit 451 is the temperature at which books burn.) But recently a quote from an 18th century poet – “Where they will burn books, they will burn humans” – was circulated in response to a pastor in Tennessee who held a book-burning bonfire, and she could no longer joke about it. “It felt way too close to home,” she said. “It was terrifying.”

For carrying books in their libraries about different gender identities and adolescence, librarians “are having people call the cops on them and saying they’re not fit to deal with children. They’re losing their jobs, and they’re being demoted. And it’s just really hard for a lot of them right now. There’s very low morale. There’s a lot of fear.”

Kirstin Pekoll, American Library Association

Some librarians suffering from harassment and intimidation are seeking professional help for their depression, anxiety and feelings of panic. Marian has been trying to find a therapist, but so far no one is available to treat her during her off hours. Hickson also turned to therapy for the first time in her life, along with medication for anxiety and an app called AbleTo that offered mental health therapy and coaching.

Hickson found visualization techniques particularly helpful. When she’d feel herself sinking under the weight of all the ugliness she was dealing with, she’d imagine herself relaxing on the Jersey Shore. She also learned a technique to question negative thoughts that were spiraling out of control. She had the opportunity to test her acumen when she heard that book protestors had gone to the prosecutor’s office in an attempt to get charges filed.

“‘Oh, my God, they’re gonna have me arrested, I’m going to have to go to jail, and on and on and on,” she remembered thinking. But then she looked at the facts. “No, all you’re hearing is this talk about it. But has anyone come to you to say that you’re going to be arrested? No. And, you know, worst case scenario, if somebody did come and attempt to arrest you, I’m a member of a union that would help me and provide attorneys.” However, no charges materialized.

Hickson, who returned from her medical leave after Thanksgiving, also found support among her peers, as well as community members and current and former students who champion intellectual freedom.

When a book titled This Book is Gay was challenged at a virtual meeting of the North Hunterdon-Voorhees Regional High School District school board on January 25, Joseph Maimone stepped up to speak. The 2012 graduate of North Hunterdon High School introduced himself as a suicide researcher at Harvard University and explained why books reflecting LGBTQ themes were so important.

“When I was a student here, I did not benefit from an encouraging environment shaped by equity and inclusion,” he said “I faced bullying and shaming. I’d raise my hand, students would yell ‘faggot’ from the back of the classroom, and my teacher wouldn’t even acknowledge it happened.” The attacks got so bad, Maimone said, that he was hospitalized after he told his guidance counselor that the bullying made him want to die.

This Book Is Gay, Maimone said, provides “acceptance for the reader” and information on safe sex practices, which is often lacking in health classes. School libraries may be the only place where vulnerable students can access such books, he added. “I was kicked out of my home when I came out. The reality is that possession of this book at home is not without real danger. As a result, the safest place for our students to access this knowledge is at the school in the library.”

A Texas librarian who included anti-racism books in her work said the backlash “felt so violent, and the nature of the posts were so angry and hateful.” She began having panic attacks and felt too threatened to go places in her own neighborhood.

From an interview with “Marian,” a Librarian Who asked for Anonymity

When librarian Brooky Parks created an LGBTQAI+ program and an anti-racism workshop for youth of color at the High Plains Library District in Weld County, Colorado, to provide a safe space for teens to talk about subjects that might be taboo at home, she was ordered to cancel them. She said she was told they violated the district’s ban on running “polarizing” programs and also was directed to get rid of the word “woke” in a national reading program known as ReadWoke, because the word was polarizing. When she challenged these requests as discriminatory, she says, she was fired.

Asked how she was doing, Parks burst into tears. “It’s definitely been extremely stressful,” she said, mentioning worries over money and unemployment. Parks, who has two kids of her own, worries how her students in the clubs will fare without extra support. “I’m extremely passionate about working with teens, and I know their challenges and struggles…It’s very discouraging to feel like what I went to school for, and got my Master’s degree in, and am supposed to be expert in (has been taken from me). I can’t do my job.”

In Texas, a group of four librarians created a group called the FReadom Fighters to combat the anguish and isolation that many librarians now feel

Interview with co-founder carolyn Foote

High Plains Library District spokesperson James Melena said Parks’ firing was “an internal HR matter” and that the district offers a wide variety of diverse programming. “We have had and will continue to have LGBTQAI+ informational panels where the panelists talk about their experiences and insights – that is informational and doesn’t push a viewpoint or agenda,” he said. “But if in the program the panelists actively encouraged attendees to become advocates for their cause, we would consider this polarizing.”

Parks has filed a charge of discrimination against the district with the Colorado Civil Rights Division and Equal Opportunity Employment Commission.

Librarians join forces to defend profession

In Texas, a group of four librarians created a group called the FReadom Fighters to defend the freedom to read and combat the fear and isolation that many librarians now feel. Its first act last November was to flood the Texas State Legislature’s Twitter page with tweets about favorite challenged books. The impetus for their activism was an inquiry that Texas State Senator Matt Krause sent to schools about 850 books that might make students “feel discomfort, guilt or anguish.”

FReadom Fighters cofounder Carolyn Foote says the group has organized “FReadom Fridays,” when it asks librarians to tweet photos of themselves in powerful poses.

“You just stand with your hands on your hips, and it’s supposed to make you feel more powerful,” she said “We just wanted people to be proud to be a librarian, instead of this kind of shame feeling that’s being put out there about our work.”

Their work has made a difference for “Marian,” who has found comfort in the support of other librarians. “Being part of that network reminds me that being complicit is not an option right now,” she said. “When decisions are being made that are bad for kids, I’m not going to remain complicit in those decisions.

Since Martha Hickson wrote a blog about her experiences of being targeted in the School Library Journal, she has been showered with letters of support from current and former students and parents, community members and people as far away as New Zealand. She and others fighting the book challenges won a victory at the January school board meeting, when the board decided to retain the books that had been challenged last fall.

But she still sees the reverberations in the community. Hickson grew up just 30 minutes from where she works today and all of her family and extended family lives here.

“I think people just forget that there’s a human being on the other side of this,” she says. “It’s important for me to try to see this from the point of view of the parents challenging books. I recognize that they think what they’re doing is best for their children. And I honor they want to do what’s best for their children. But they have to stop at their own front door.”

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.