What actually happens in WA when someone’s not competent to stand trial

Many people are caught in a vicious cycle: They are deemed ‘restored’ to competency, sent back to jail, and destabilize again.

This article was originally reported and published by seattletimes.com. Republished with persmission.

A new ward called F-9 opened at Western State Hospital in Lakewood, Pierce County, this May. Eldorado Brown, a 40-year-old man coming from the King County Jail, can tell because it smells like fresh paint.

Brown, who is facing felony charges and has a history of mental illness, was among the first patients transferred here as 29 beds opened for people awaiting mental health services from jails.

Facing a surge in demand from local courts, Western State is expanding the amount of space it has for patients like Brown — people sent to state facilities for restoration treatment or attainment, a kind of basic mental health service that aims to make defendants competent to stand trial.

Between 2013 and 2021, competency referrals more than doubled across most counties, according to data from the Department of Social and Health Services. To keep up, the hospital is investing $612 million in the construction of a 350-bed hospital, set to open as early as 2028.

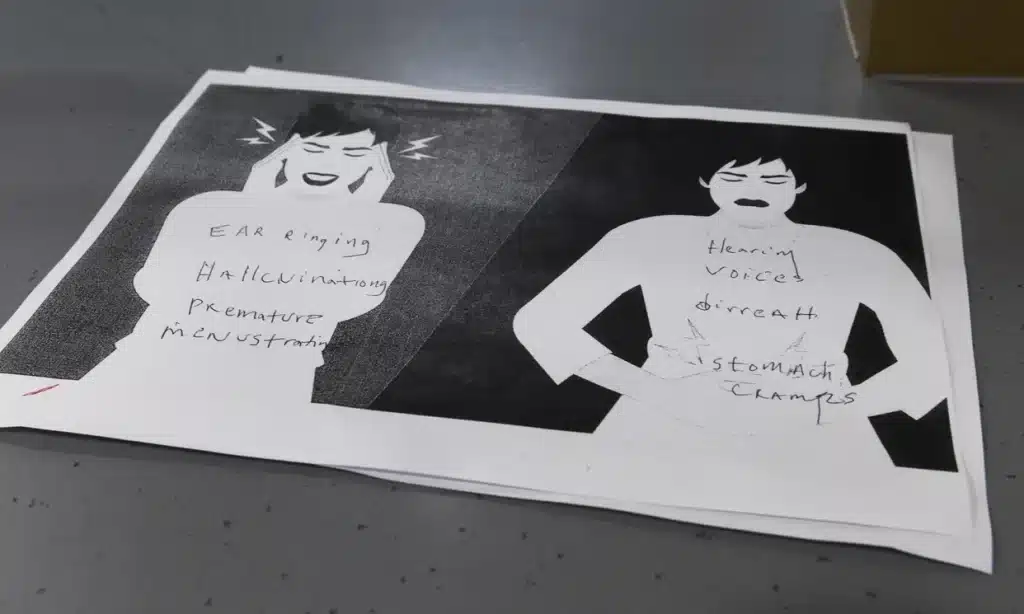

But as the state’s largest psychiatric hospital receives more and more of these patients, what does the restoration process actually look like? The treatment is extremely limited, often only providing medication and a basic education about the criminal legal system.

A new ward called F-9 opened at Western State Hospital in Lakewood, Pierce County, this May. Eldorado Brown, a 40-year-old man coming from the King County Jail, can tell because it smells like fresh paint.

Brown, who is facing felony charges and has a history of mental illness, was among the first patients transferred here as 29 beds opened for people awaiting mental health services from jails.

Facing a surge in demand from local courts, Western State is expanding the amount of space it has for patients like Brown — people sent to state facilities for restoration treatment or attainment, a kind of basic mental health service that aims to make defendants competent to stand trial.

Between 2013 and 2021, competency referrals more than doubled across most counties, according to data from the Department of Social and Health Services. To keep up, the hospital is investing $612 million in the construction of a 350-bed hospital, set to open as early as 2028.

But as the state’s largest psychiatric hospital receives more and more of these patients, what does the restoration process actually look like? The treatment is extremely limited, often only providing medication and a basic education about the criminal legal system.

Medication can help people with severe mental illnesses, Khandelwal said. But she points to the thorny issue of what happens afterward: People are deemed restored, get sent back to jail, and destabilize again. Or their charges are dismissed and they are discharged, potentially into homelessness, and sometimes cycle right back into jail. In the best case scenario, defendants might be diverted into an alternative program that links them to treatment or housing — but those are rare and limited spots.

For prosecutors, restoration is a step toward treatment, albeit an imperfect one. In many cases, it’s one of the few ways they can keep people out of jail and off the street, especially if the defendant is arrested repeatedly.

“We’re not looking for restoration just for the sake of holding someone accountable,” said Seattle City Attorney Ann Davison. “It really is to try to stem off that longer exposure … [of] decompensating.”

Davison points to times that a defendant was deemed competent but then spent years cycling through homelessness and untreated drug use or mental illness. Ultimately, they deteriorated and were no longer competent.

The process

Part of the criminal legal system hinges on the foundational idea that a person accused of a crime has an understanding of their actions — a defendant has to have mens rea, Latin for a “guilty mind,” to be charged. This comes from medieval British law where people with mental illness or an intellectual or developmental disability were charged less severely than a person who was competent and conscious of their actions.

In modern times, if a defendant is not able to cooperate with their attorney (say answer questions coherently) or doesn’t understand the criminal process (what a trial is, who the judge is), a defense lawyer can flag the case for a competency evaluation. That is called the Dusky standard and it’s what most states use to evaluate people with competency issues. Ultimately, this system is a balancing act, pivoting between the rights of victims and the constitutional rights of defendants to due process.

Once ordered by a judge, Washington law requires a competency evaluation to be done within two weeks by a mental health professional with doctorate level training, known as a forensic evaluator. That’s done through an in-person or video interview. Evaluators gather the defendant’s medical and personal history, take note of their symptoms, and file a report to court with their findings.

If an evaluator finds that person to not be competent, the defendant goes on a waitlist to get into one of the state’s psychiatric treatment facilities. There, they undergo restoration treatment: In most cases, this can take about a month for a misdemeanor charge or 90 days for a felony charge, with the possibility of extensions.

Mental health can't wait.

America is in a mental health crisis — but too often, the media overlooks this urgent issue. MindSite News is different. We’re the only national newsroom dedicated exclusively to mental health journalism, exposing systemic failures and spotlighting lifesaving solutions. And as a nonprofit, we depend on reader support to stay independent and focused on the truth.

It takes less than one minute to make a difference. No amount is too small.

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.