The Night Parade: A genre-bending memoir that helps reshape the cultural narrative on bipolar illness and grief

Jami Nakamura Lin has written a rich, exquisitely illustrated memoir that expands the cultural narrative on mental illness and grief.

Debut author Jami Nakamura Lin has always struggled with what she calls “the tidy arc of the typical mental illness memoir, the kind whose trajectory leads towards being ‘better,’ though the writers usually don’t pretend they are fully healed.”

Small wonder that Lin’s own memoir The Night Parade – about her bipolar disorder, her family, and her father’s death – is anything but typical. Stories about bipolar illness, Lin observes, often focus on the worst moments, “crisis’s hot center.” And though she recounts her suicide attempt and hospitalization in a psychiatric ward when she was 17, Lin writes compellingly of the everyday hum of living with her mental illness.

Labeled as a speculative memoir, The Night Parade is an inventive and genre-bending book that excavates illness, grief, and lineage – and suggests a cultural sea change in how we view them. Written nonlinearly and bolstered by research, it employs different points of view. One chapter is a letter to Lin’s daughter. Another is an imagined conversation between Lin and her grandparents as they travel through time.

Lin weaves her own story with folktales from her Japanese, Taiwanese, and Okinawan heritage. Each chapter opens with an illustration of yōkai or similar supernatural creatures and spirits, painted by her sister Cori Nakamura Lin. Often ghostly and sometimes monstrous, the yōkai historically personified unaccountable phenomena in the tales of Japanese storytellers. Now, they are a way for Lin to make sense of her own personal history.

I recently spoke to Lin over Zoom. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Your memoir is unlike anything I’ve ever read in the genre, which expanded my mind around what memoir could be. How did the idea come to you of using folklore from your various cultural backgrounds to tell your story?

It was an accident, because originally, I had started doing this research for what was a novel at the time. Between 2013 and 2017, I was very obsessively writing this YA [young adult fiction] fantasy novel that was based on an alternate version of Japan. And I got this fellowship to go to Japan, so I went there for four months and was doing all this research for this novel. But I was having a really hard time. I felt like I was just circling around and around and I couldn’t finish it. And when I was in Japan in 2017, I found out my father was dying. And so after that, I stopped working on writing for a long time.

Then after my father died and my daughter was born and after things had settled down a little bit, I started wanting to write about that, and wanting to write about my bipolar disorder. And it was really hard for me to write about it until I started thinking about using the yōkai, this folklore I’d studied, as a way to enter these topics, because I had studied nonfiction in my MFA. But by the time I had finished in 2013, I was really sick about writing about myself. It felt like I was just tunneling inwards. And so it was funny that I used these two projects that kind of didn’t end up working out and fused them together to what became The Night Parade, and that each of them lent each other the backbone to what I needed to move forward on this.

You talked about how hard it is to write about yourself. What do you think it was about the yōkai that allowed you to unlock things that would have been otherwise difficult to unlock?

I think part of it was being able to see my story in relationship to other stories. And I think when I was exhausted about writing about myself, I could write about something else. Or sometimes I could have absences or gaps in my own story, but by filling it with a folktale that had the same themes, then the reader could see from the associations, thematically, what I was talking about without having to directly engage with some things that I didn’t always necessarily want to directly engage with. So it was using these loose associations and ties and creating a web, a circular web.

And also by having it be speculative, it made it a lot more entertaining for me to write about. It made it interesting for me to write about things that were difficult for me to write about. Other [times] I had told the story so many times that the story felt calcified. It felt dead. And by looking at it in a new way, by writing about it in third person, or in future tense, or by using a time travel portal, it allowed me to look at things askew. I think it allowed me to see it new and to see it in a real and different way.

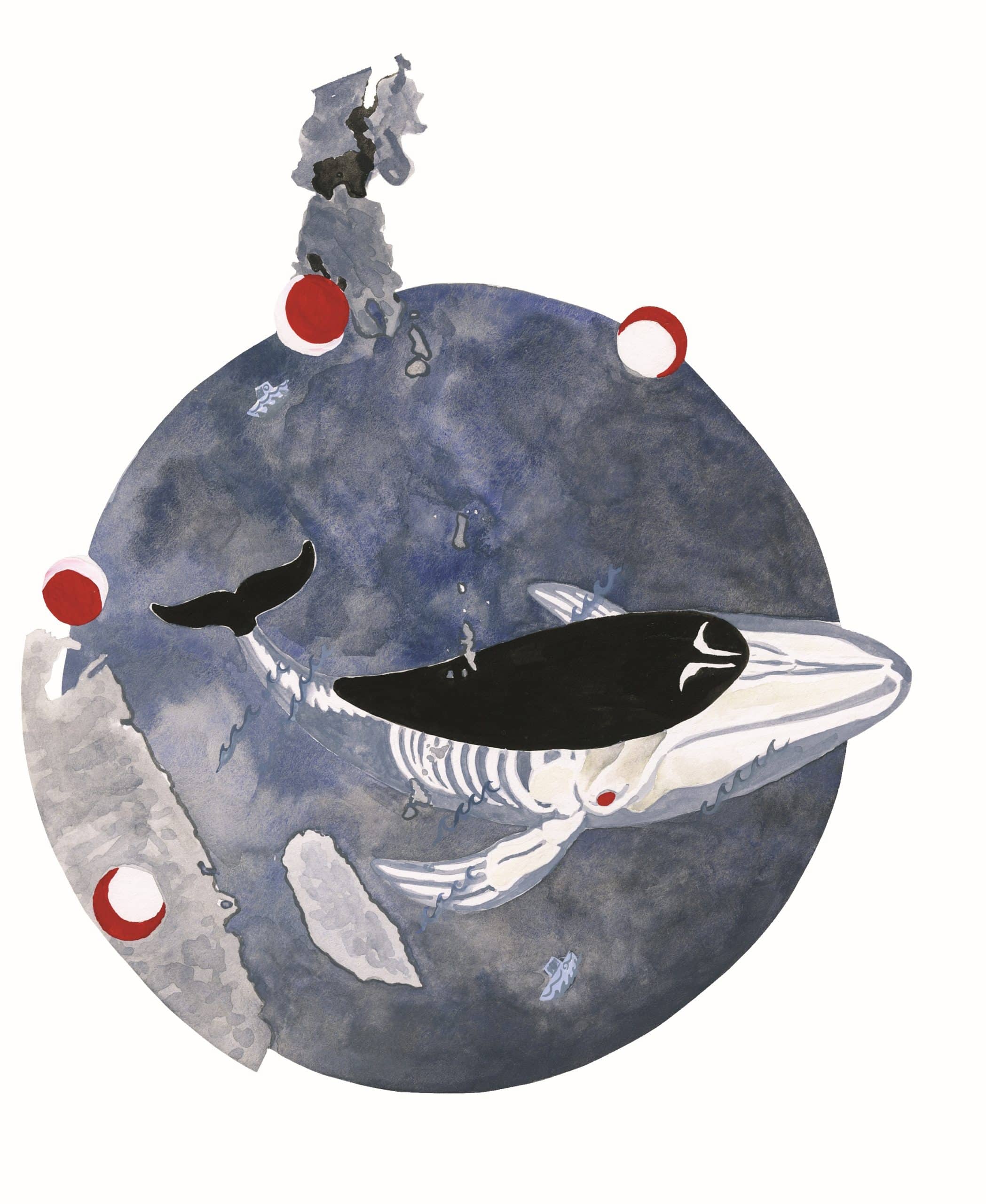

Can we talk about a specific example? In the chapter “The Offing” you write in the third person about your mental health struggles when you were a teenager before you were diagnosed as bipolar. You also write about the bakekujira, these ghost whales. At first they seem separate. But then there’s this line that brought it together for me, “An event in the past does not stay in the past.” The piece is about different types of hauntings. Can you talk about how you put those strands together?

I had thought that they were loosely associated at the beginning. But that was one of the chapters I had the most difficult times with. It went through four or five different drafts where my editor was like, “This just isn’t working.” And I knew it wasn’t working. That chapter felt like it was haunting the whole book because I just couldn’t get it. And I knew that I had to stick to the ghost whale, the bakekujira, because my sister had already painted it. I think if she hadn’t already painted it, I might have been like, “This isn’t working. Let’s do something else.” But because she had already painted it, I was, “I have to figure out how it’s connected.” And it ended up being deeply connected, but it just took me so long to see how it was.

I think on a meta level, it was haunting the text. There was this story by a Japanese manga creator who was also writing about the bakekujira. But he started getting really sick. And he was like, “Oh, this is the curse of the bakekujira.” And then when he put the project away, he started feeling better. And so I feel like it does haunt people who are trying to write about it in different ways – that it took me so long and it was so strenuous.

But when I started writing about it from the specific idea of thinking about time, and how time stops and starts again, and looking at it from that specific point of view, it really made it more interesting for me to write. It allowed me to have both distance but also closeness in it by being able to think about, “Oh, what does the bird outside my window think because time has stopped? She’s worried about her eggs not hatching.” And just thinking about time as this fluid space. I think letting myself lean into that kind of speculative weirdness really brought the strands together.

There’s so much in your book about memory and myth as a way of preserving memory – and that’s tied into the way we tell stories. There’s something here about how telling stories is so important for mental health or just being human.

I feel like telling stories is so important for us as part of being human – and I think also specifically for mental health. I studied psychology in undergrad, not English. And my senior project was about autopathography, which is writing the narratives of your own illness, and how that helps people. I think being able to tell your own story is like trying to have agency over what happened to you. Because with a lot of different chronic illness, mental illness, and things like that, it can often feel like we don’t have agency, especially with the systems that we have in America. It feels like we’re stuck by not having choices – sometimes which doctors we go to, or which medications we take, or what jobs we can have that fits with what our needs are.

I feel like having these rituals that a lot of other cultures have about grief is so powerful as a way to keep [our loved ones who’ve died] alive with us…I will carry my sadness about my father my entire life, and it’ll transform. But it’s not something that I want to put away. It’s deeply a part of me in a way that I do appreciate.

Nakamura Lin on her father’s death and the power of ritual

By telling that story it can be an extension of how sometimes having a diagnosis can feel like we have agency because it ties us back to community, right? Having a name for what’s happening to you can also help you find other people with that name. And a diagnosis is not an end all be all. I feel like it can be what you make of it. I do feel like once I had the word bipolar attached – and then later I was diagnosed with ADHD when I was writing this book – I felt like, “Oh, now I have tethers to the community. I can understand how other people support each other, how they support themselves.” And I can see it become legible in a way. When I was just thinking, “I have all these tiny little things that are idiosyncratic and only happening to me, and I don’t know why it’s happening” – it felt very confusing. But when it aligned into a story then it can cohere into a way that can help you make sense of things.

One thing I was thinking about while I was reading this book was how Asian American girls have some of the highest rates of depression among their peers. Your book speaks to that, to the depression and also rage that girls experience. You write, “To be bipolar is to be hungry, by which I mean to be bipolar is to deny your hunger. But the same could be said about being a woman, about being a girl.” I was wondering if there’s something specific about being an Asian American girl or woman that is especially hungry-making?

Yes, I think specifically the way that we are expected to present in the world and also externally by American society, but also, I think culturally how we’ve been raised by our own communities. In the Japanese American community I grew up in, I never saw anger. I never saw anyone be angry with each other. It was always you just swallowed it and you held it inside. And maybe you just thought about it for 20 years, but you never talked about it, right? So I never saw positive ways of anger being expressed.

It’s interesting because I feel like my parents weren’t angry people, like they almost never disagreed. Whenever they did have disagreements, I think they did it themselves, not in front of us. I think my father intentionally did that because he had seen his parents fight and that was really hard for him. So he didn’t want to have to have us see that. So it’s interesting to see how this goes down through the generations or how each generation tries to do things or change things for the next. But I definitely feel like in many Asian American cultures, especially for girls, it’s very shameful to have this anger to not be controlled. Like we’re supposed to be very controlled in many ways, like on top of things. And anger feels like this looseness, this loss of control that you’re not supposed to have or do.

I appreciate how you write about embodiment and the way mental illness feels in your body. And some of these yōkai are grotesque beings, like the rokurokubi, whose heads come off. They go around at night sucking blood from people, and they may or may not even be aware of what they’re doing. Therapists are always asking how you feel in your body, but in the general public, I don’t think people really talk about the ways in which mental health affects your body.

Exactly. I think before I was diagnosed with bipolar, I just didn’t really understand how it was connected – the way that this agitation I felt in my body was so connected to what was happening in my mind. I went to get a massage and then afterwards my mind and my body were totally depleted. And my sister was telling me, “Body work is so exhausting because all this stuff is moving through your body.” One of the main medications I take, my mood stabilizer, is an anticonvulsant because it’s also used for people who have epilepsy. That’s the only way that my mind can be calm too, is if my body can be calm because it’s just so related. I do think, like you said, therapists know. And I think we’re getting a more emerging sense of how it’s connected. But we think of it as so separate.

Your memoir is also about grief. There’s grief towards your younger self, over your miscarriage, and of course, when your father died from cancer. You write about how in this society, we struggle with what to do with the grief, with displaying grief. Writing was one way of processing that.

I do feel like the writing helped me both process the grief, but also keep it alive in a really powerful way for me, especially for my father, because while I was writing the book, I was in this grief-liminal world where I dreamed about my father so often. He was just with me all the time because I was so deep in writing about it. And when I stopped writing the book, I stopped dreaming about him for a long time because I just wasn’t thinking about it so deeply every day. So then I lost that part that had kept him with me through the night. And recently I’ve been dreaming about him more again. He died on December 28th, so we’re in the grief season. On January 10th, it’s his birthday, and we’re going to celebrate that with my extended family because it’s been five years.

I feel like having these rituals that a lot of other cultures have about grief is so powerful as a way to keep them alive with us, and a way for us to do it together where it’s not just grief we’re holding separately in our hearts, but a communal type of grief. There’s such huge power in ritual. And I think a lot of Western cultures don’t have that type of ritual around grief. And then it can be really hard because either you’re holding it alone, or people are telling you, or you’re thinking yourself, “Why am I still so sad about this?” I will carry my sadness about my father my entire life, and it’ll transform. But it’s not something that I want to put away. It’s deeply a part of me in a way that I do appreciate.

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.