“How Not to Kill Yourself”: A Writer’s Advice

Author Clancy Martin writes about his own struggles with attempted suicide and includes his best reframing advice– live another day, and then another.

Warning: This review may be disturbing to some people. If you have had thoughts of suicide or harming yourself, call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline and connect in English or Spanish.

The first time I told someone I was feeling suicidal – an ex-partner – he was so sad and fearful that I swore I’d never tell him again, no matter how badly I was feeling. It wasn’t until years later that I would find my tribe in a dingy hospital meeting room: a group of people with bipolar disorder and depression, who could listen to others talking about feeling suicidal and nod along, supportive and understanding. Those discussions were absent of the shock and horror that well-meaning family and friends felt, feelings that ironically added an additional layer of isolation and loneliness to what is already a challenging, sometimes harrowing, set of feelings to navigate.

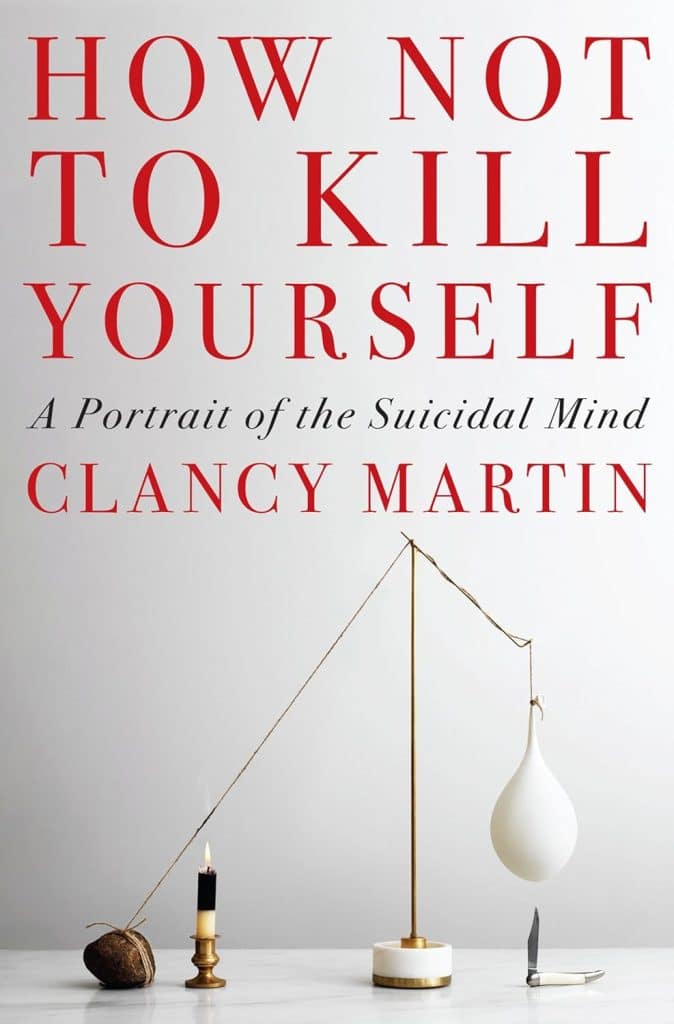

In How Not to Kill Yourself ( Pantheon, 2023), author Clancy Martin opens by talking about one of his suicide attempts. Afterward, he’s recovering and on the phone with his wife. She asks him what’s wrong and he tells her he’s just got just a bit of a sore throat. That one can have a wife, an intimate relationship, someone who’s vowed to see you through sickness and until death, but not be able to tell her about this kind of suffering is telling. And it is this additional bubble of loneliness, stigma, and secrecy that Martin is trying to burst, for anyone who has ever felt suicidal. He hopes that in dissecting his own suicidal feelings, and the feelings of our culture at large, that he might cast a little light on this oft-kept-secret realm.

For those of us who have had suicidal feelings or attempts, Martin’s book places us in the good company of others who understand. He tells us it is part of the long mission of destigmatizing thoughts of suicide and therefore removing their power; in the preface he normalizes those thoughts, framing them as a part of humans’ instinctual death drives, something psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud talked about being as intrinsic to humans as a sex drive.

Some experience this directly in suicidal fantasies, and some less directly by, say, a habit of binge drinking or even a meditation practice to separate us from the pain of living. If a death drive is normal, we can start to talk about it freely, and resist magnifying the original pain with added loneliness and shame.

How Not to Kill Yourself is a mix of memoir (with frank and sometimes graphic descriptions of Martin’s suicide attempts), philosophy, and analysis of literature from authors who killed themselves or attempted to. His aim is to prevent suicides; he believes that “for the vast majority of people, suicide is a bad choice.”

Martin also talks extensively of his struggles with alcohol addiction and how alcohol relates to suicidality. He points out that when talking of suicide, we must also talk about addiction; 25% of those with chronic alcohol and drug addiction kill themselves. He finds the AA model quite limited, however. While transformative for many, it leaves out the 50% of people in recovery who don’t or can’t follow an abstinence model. He also argues that AA culture has historically been resistant to medication assistance – both psychiatric medications and medication-assisted therapy for people who cannot control their drinking That’s a fundamental weakness, he argues, because alcohol is a “very effective and potentially addictive medication for a whole host of psychological and neurobiological problems.” The side effects and risks of alcohol are terrible, but so can cutting it out without offering the body an alternative.

Martin incorporates research on suicide throughout and includes an appendix of interviews with people looking hard at suicide in various ways, but the book is squarely planted in one (white, cis, heterosexual) man’s point of view. He talks about the suicidal mind, but really, he can only talk about his own suicidal mind. Everyone experiences suicidal thoughts differently. An ex-boyfriend told me that his thoughts of suicide always follow mistakes he’s made (“Why don’t you just kill yourself, then?” he asks himself) in a distressing loop.

Mine, on the other hand, tend to come with restriction, boredom, and the feeling that life stretches out infinitely in a series of difficult and impossible tasks (even when I’m not depressed). Martin gives detailed instructions on what has worked for him, which is limited, of course, by being what has worked for him.

At the core of the book is the notion that most people with suicidal thoughts actually have a chronic affliction. They may rid themselves of the acute feelings of a particular episode, but that means the thoughts are in remission, not gone. Some may find that defeatist. But following Buddhist practice, Clancy asks people to change their relationships to the thoughts. Don’t try to smash them as soon as they come but let them come and pass and try to ease the pain and discomfort – and delay, delay, delay any suicidal action.

Martin has some astoundingly practical advice for people feeling acutely suicidal and people close to someone who is. Put it off for one day. Change something small about your environment (get outside, change the music or lighting, advice you might give someone who is having a “bad” psychedelic trip). There’s no rush in a decision with so much finality, he says: “I can always just kill myself tomorrow.” And if you can delay a day or so, or convince a loved one to wait, that may mean the difference between life and death. That advice seems so much more palatable to someone in a dire state than trying to talk them (or yourself) out of suicide now and forever.

His advice in the book veers from very specific (give up your guns, now; get off social media; quit addictive substances) to spiritual arguments against suicide. He says, according to some belief systems, those who die by suicide may be doomed for eternity to repeat life; suicide may not be the escape that people hope it is. And that advice can be practical. When one of my friends was suicidal, she said ultimately, she couldn’t do it because there was a chance that it would mean instead of escaping this life, she would be doomed to repeat it forever.

Martin quotes stoic thought: Stoics posit everyone has the right to die. But he points out that humans are so interconnected that suicide is essentially burning down a house that many people live in. He quotes many who argue that offering a legal path to suicide (with requisite hoops to jump through) could actually reduce suicides. People may not be as likely to impulsively choose it and may actually be diverted by bureaucracy (a chance to have intense feelings pass, as they tend to do).

One of my favorite parts of the book is in the appendix, in an interview with John Draper, an expert on suicide prevention. Draper says to people who have survived an attempt, “Now you have a gift…You can help others in a way that other people can’t.” He says they’re the real experts on suicidality. This framing is so important in a time when one-third of teen girls report having considered suicide. There is such power in someone talking about being to the other side and back. Most people who survive an attempt are grateful that the attempt failed later on. Ken Baldwin survived jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge and said that immediately after leaping, “I realized that everything in my life that I’d thought was unfixable was totally fixable – except for having just jumped.”

I was recently reporting in a remote village in Alaska and there was a suicide while I was there. The cultural beliefs surrounding it meant families kept people, especially youth, inside that first night afterwards. They feared that the suicidal person, before disappearing from earth forever, would try to take more living with them. It struck me as an apt and sensible response to loss, and one that has likely saved lives, getting people at least to their next day. And that, I think, is what Martin is doing with this book – keeping us company in the lonely night, keeping us with our families or friends or animals or our own self for one more day. He’s convincing himself of the possibility of just choosing “no” for now, and he’s bringing us along for the ride.

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.