Troubled Teen Industry Is ‘Taxpayer-Funded Child Abuse,’ Senate Report and Paris Hilton Say. Where Are the Government Regulators?

Physical abuse, rape, and emotional trauma is endemic to psychiatric residential treatment centers for kids and youth nationwide.

Neglect and physical abuse of at-risk youth is ‘routine’ in residential treatment centers, which rake in billions thanks to Medicaid, charges Sen. Ron Wyden

Cornelius Frederick was known as a jokester by other kids at Lakeside Academy, a Michigan facility for troubled youth owned by Sequel, a residential treatment chain. When the 16-year-old foster child threw bits of bread from a sandwich at other kids in the cafeteria in April 2020, he’d already been physically restrained by staff members 10 times in the six months he’d spent there, according to a state investigation and legal depositions.

But this time, several staffers piled on him, and held him face-down for 12 minutes, as he slowly suffocated to death, a scene that was caught on camera.

A medical examiner ruled the death a homicide, and two staff members pleaded no contest to charges of involuntary manslaughter, while an on-duty nurse was charged with felony-level child abuse for failing to provide medical care or call 911 for 12 minutes after finding Frederick unresponsive. A judge decided the death resulted from poor training and oversight, and the three employees received probation.

No executive of the facility, which closed a few months after Frederick’s death, or Sequel Youth and Family Services, the chain of treatment centers that owned it, has been held to account. Many of Sequel’s treatment centers were sold or shuttered after being hit with abuse allegations, and some now operate as part of a mysterious new chain called Vivant Behavioral Health that has no website or listed phone number. Both Sequel and Vivant were founded by a former Jiffy Lube executive, Jay Ripley.

Investigators who put together a report on the troubled teen industry for the U.S. Senate Finance Committee say Ripley used Vivant to buy troubled Sequel facilities that are in legal jeopardy as a way of changing owners and dodging accountability.

For more than three decades, investigative journalists and advocates have been exposing the abusive behavior, violence and degrading treatment of children taking place in many of these teen treatment centers. Yet the facilities have continued to operate, with little apparent change in the types and frequency of abuse.

But today two things have changed: The revenue streams that support these companies increasingly come not just from self-paying parents or private insurers but from tax dollars provided by the federal Medicaid program and state child welfare systems. These funds continue to flow despite the fact that the companies are mired in lawsuits charging them with abuse, according to the Senate report.

Now, only about a quarter of youth are placed in these programs by parents, according to estimates by the American Bar Association. Instead, most come from subsidized foster care, specialized disability education programs, juvenile justice referrals and frantic middle-class parents who can’t afford pricey care and relinquish custody of their children to the state to get help. All this keeps the programs stocked with a fresh supply of at-risk kids – whose families often have few resources and little power.

The second big change is that the children once treated in these facilities – and in some cases, their parents – have become increasingly effective advocates working to expose and end the horrors they were subjected to, including sexual abuse, which the Senate report concluded was “endemic to the industry.” Outraged by the lack of meaningful oversight by state and federal authorities, activists have built a movement to fight against the “troubled teen industry,” launching organizations like Unsilenced. The group has compiled a database of 399 youth and young adult deaths allegedly linked to teen treatment facilities and created a website to share survivors’ stories. (See sidebar for more on the survivors’ movement).

Many also worked closely with the staff members who produced the Finance Committee report, “Warehouses of Neglect,” that documented widespread trauma in the treatment centers. The report details physical and emotional abuse, sexual assault, restraints, seclusion, deaths from suicides and caretaker abuse. In many programs, the report finds, children were exposed to bedbugs and lived in buildings in states of “gross disrepair,” supervised by poorly trained or abusive staff. One lawsuit links sexual abuse to the “rampant spread of HIV” among the children at one facility.

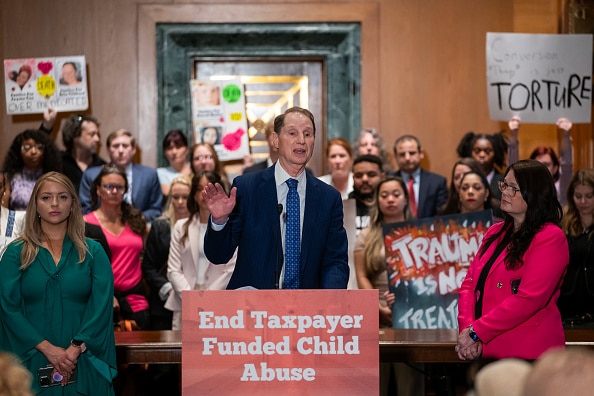

“The system is failing, except the providers running these facilities, who have figured out exactly how to turn a profit off taxpayer-funded child abuse,” said Senator Ron Wyden (D-Oregon), the committee’s chair, at a hearing on the report.

Four major players were named in the report:

•Acadia Healthcare, a Tennessee-based, publicly traded company that runs 253 behavioral treatment centers, is valued at $6.5 billion and gets 53.9 percent of its revenue from Medicaid, according to the report. Media accounts have reported widespread sexual assaults and beatings of out-of-state foster care children at Acadia centers. Acadia has plans to expand its residential treatment centers, according to the Senate report.

•Devereux Advanced Behavioral Health, a nonprofit chain that gets 95 percent of its residential treatment center revenue from Medicaid, according to the Senate report. It faces a class action lawsuit alleging widespread sexual and physical abuse at facilities in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Arizona and Texas, including allegations that staffers raped developmentally disabled youth for years in facilities near Philadelphia. A separate May 2024 lawsuit was also filed against the Devereux Foundation by 18 former patients charging sexual abuse.

•Vivant Behavioral Health, a secretive, privately held chain with no public website and a president who won’t reveal his last name on his LinkedIn account, told the committee that half of its facilities get more than 75% of their revenue from public dollars. Vivant, co-founded by Sequel owner Jay Ripley in 2021, purchased 13 facilities from Sequel Youth and Family Services after the chain was plagued by allegations of abuse. Since July 2022, when the committee began its report, Vivant has divested from nine facilities and retains four.

•Universal Health Services (UHS) is one of the largest U.S. providers of behavioral healthcare, with more than 330 residential facilities and a market value exceeding $15 billion. In 2023, its behavioral health division generated $6.2 billion in revenue, 39% of it from Medicaid, according to the committee. Many of its facilities have histories of abusing foster child patients, according to a recent investigation by Mother Jones. Its Cedar Ridge Behavioral Hospital in Oklahoma was singled out in the committee report for failing to provide minimum care and for failing to protect a child from repeated sexual abuse by a staff member, even after learning of the abuse.

Although deaths in wilderness therapy camps and other teen ‘treatment’ facilities go back decades, reports of mistreatment and deadly restraint continue to surface. This February, a 12-year-old boy died overnight after being transported against his will to the Trails Carolina wilderness program in North Carolina. Only after the boy’s death did the state remove 18 residents from the facility, which was the subject of more than 100 complaints and lawsuits, as compiled by Unsilenced.

The boy, said to be “loud and irate” on arrival by a counselor, was zipped into a sleeping bag with an alarm on the zipper and apparently had a panic attack after midnight. A spokesperson for Trails Carolina said the death was an accident and that newly arrived children are treated with “compassion and patience.” But an autopsy this summer determined the boy died by suffocation in the sleeping bag and his death was ruled a homicide.

One teenage girl who asked to be identified only by her first initial V, spent time at the program a few years ago and described her experience to MindSite News. She said she was sent to Trails Carolina in 2020 at the age of 12 for being “disrespectful” and soon found herself in shock. “It was really a terrifying experience,” V said. She was strip-searched in a shed upon arrival and soon found that she and other children were barred from speaking to each other without staff permission. She also describes the hikes they took as painful and demoralizing.

“I had to hike for six hours a day, with, like, 50-to-75-pound backpacks,” she said, adding that the process left her with a back injury that lasted for months. She recalls that one exhausted girl, refusing to hike, was dragged by her arms by staffers through the woods. V spent about 20 minutes a week in superficial talk therapy, she said, and the program cost her parents about $36,000 a month.

‘Abuse and neglect is the norm’: Senate report

Weak government oversight and workplace cultures that ignore the needs and dignity of children remain common in “troubled teen” facilities, according Wyden, who oversaw the Finance Committee report on the industry.

Children are subjected to a near-constant barrage of

Wyden Senate Report, quoting From “Desperation Without Dignity”

verbal abuse from staff. Staff curse, yell, make demeaning and derogatory comments, insult and

make fun of the children. At a Sequel facility in Alabama, girls reported being

called ‘f-ng fat,’ ‘f-ng ugly,’ ‘bitch,’ ‘stupid,’ and ‘ignorant.’

“More often than not, abuse and neglect is the norm at these facilities,” Wyden said at the opening of hearings. “It’s clear that the operating model for these facilities is to warehouse as many kids as possible while keeping costs low in order to maximize profits.”

That was the case at Michigan’s Lakeside Academy, where Cornelius Frederick died, according to Meghan Kennedy, the program’s former director of case management. She told MindSite News that dangerous restraints and conditions were a regular feature at Lakeside and that administrators and a state licensing inspector encouraged staff members to keep quiet about problems.

“Right before Cornelius, there was a kid who had a dislocated shoulder and had bruises everywhere,” she said. Despite the push for silence by staff members, in the 18 months prior to Cornelius Frederick’s death, emergency services were summoned to the facility 237 times, including calls regarding sexual assault and child abuse allegations, according to law enforcement and 911 records compiled by NBC News. Kennedy was also pressured to avoid calling Children’s Protective Services (CPS) after seeing youths who were badly injured by staff.

“They didn’t want us calling, they didn’t want things going outside” the center, she said. “The couple of times that I called CPS, the students had bruises, they were injured, and this kid isn’t making this up.”

‘Trauma is not treatment’

“End Taxpayer-Funded Child Abuse.” That was the sign displayed on the podium in a Senate hearing room where Theresa Payne and other advocates spoke at a press conference. Some hoisted signs saying, “Trauma Is Not Treatment.”

Payne, a solemn 56-year-old retired social work consultant, told the crowd that neglect and physical attacks by staff killed her 14-year-old daughter Monique at a UHS facility in Massachusetts called Westwood Lodge where she was sent after private therapy didn’t rein in her wild ways. She said staff knew Monique had a benign brain tumor and had to be treated carefully. “Never in my life did I think that five months later she would be leaving in a casket,” Payne said.

The facility was closed in 2017, but MindSite News has learned that a police investigation into Monique’s death has been opened and a new witness has come forward.

Wyden and other critics say the lack of real accountability and oversight has made such tragedies inevitable, allowing a scandal-scarred industry to continue operating for decades, while failing to protect youths like Monique, Cornelius and hundreds of others who have needlessly died in residential treatment for troubled teens.

After a two-year investigation and a review of 25,000 documents, Wyden’s committee report concluded that the troubled teen industry was making billions of dollars from federal and state health, education, juvenile justice, and child welfare programs – what Wyden called a “firehose of federal funding.”

The troubled teen industry houses an estimated 120,000 to 200,000 young people a year, according to the American Bar Association, but there’s no precise government data, a shortcoming that a recently-introduced bill backed by reform groups, Paris Hilton and more than 100 members of Congress aims to remedy.

The system is failing, except the providers running these facilities, who have figured out exactly how to turn a profit off taxpayer-funded child abuse

Sen. Ron Wyden

Ownership of the youth treatment industry includes many private equity firms such as Altamont Capital, which invested in Sequel. A 2022 report by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project lists more than 60 youth behavioral treatment programs owned by these firms. Additionally, an unknown number of youth treatment facilities run by fundamentalist Christians have largely avoided regulatory enforcement – even after some leaders were arrested on abuse and rape charges.

Executive of the four companies singled out in the committee’s report have avoided that kind of personal accountability, and several have rejected survivors’ accusations – and the committee’s findings – as biased and blind to their accomplishments.

The committee report “is incomplete and misleading and provides an inaccurate depiction of the care and treatment provided” at its facilities, UHS representatives said in a statement sent to MindSite News. “The report wholly fails to recognize the thousands of adolescents that have been successfully treated over the years whose lives have been dramatically enhanced and quite possibly saved as a result of the care provided.”

The UHS statement went on to “acknowledge that there have been incidents over our many years of dedicated service at some of our facilities where the treatment of residents have not met our expectations and (residents) have suffered harm. Such incidents belie our commitment to provide a safe and therapeutic environment.”

Vivant, Acadia and Devereux and other companies named in the Senate report did not respond to requests for comment from MindSite News.

Mark Miller, the CEO of UHS who earns $15 million a year, declined to appear before the committee, and a symbolic empty chair was set aside for him at the hearing table. “You’re just left wondering,” Wyden said, “was he just too scared to face survivors of his own facilities in person?”

Paris Hilton gives ‘voice to the children whose voices can’t be heard’

The push for reform has also been assisted by high-profile revelations from celebrity model and businesswoman Paris Hilton. She went public with a YouTube documentary This is Paris in 2020, which now has 80 million views. In it, she disclosed her alleged sexual and physical abuse as a teen at the notorious Provo Canyon School in Utah, a residential treatment center that was later acquired by UHS.

“I’m here to be the voice for the children whose voices can’t be heard,” she told a congressional committee in June.

Hilton’s testimony garnered media attention for a normally obscure House Ways and Means Committee hearing on reforming the child welfare system, which she and other advocates say is a key feeder into abusive institutional facilities. They are calling for increased funding for a federal program that aims to keep children out of traditional foster care.

“I was force-fed medications and sexually abused by the staff. I was violently restrained and dragged down hallways, stripped naked and thrown into solitary confinement.”

Paris Hilton on her stay at Provo Canyon School

Hilton has used her celebrity status and the story of her own experience to lobby for measures including the Stop Institutional Child Abuse Act (SICAA), a bill designed to increase monitoring and data collection on practices and outcomes at residential treatment programs for youth. She also has successfully pushed for oversight legislation in Utah, California and seven other states.

Hilton’s June appearance came on the same day that the HHS Inspector General released a report showing that states generally don’t track sexual and other forms of abuse against the roughly 50,000 foster care children currently in residential treatment.

“These programs promised healing, growth and support but instead did not allow me to speak, move freely or even look out a window for two years,” Hilton said. “I was force-fed medications and sexually abused by the staff. I was violently restrained and dragged down hallways, stripped naked and thrown into solitary confinement.”

Hilton’s advocacy has had a transformative impact by spotlighting eloquent, dogged survivors of facility abuse and creating an opening for them to drive policy – not be victims of it.

It also has helped attract attention from television producers. The stories of teen survivors have been amplified by the Netflix documentary series The Program and the Max documentary series Teen Torture, Inc.

“Getting help shouldn’t be a death sentence”

One voice for survivors is Sixto Cancel, a victim of the foster care system and a founder of the reform group Think of Us, who summed up what’s at stake: “Getting help shouldn’t be a death sentence.” His group is leading the fight against placing foster children in dangerous congregate care, and is instead promoting policies to place those who need new homes with family members or trusted nearby adults in what’s known as “kinship care.”

The federal Administration for Children and Families (ACF) has recently adopted more flexible standards to allow grandparents and other relatives to take in at-risk kids and receive subsidies for kinship care. Advocates say this approach not only reduces the risk of abuse but yields more positive outcomes than institutional placements.

The Wyden report calls for tougher oversight, new federal legislation to raise standards for congregate care and increased investment in community-based care – echoing earlier reform efforts that went nowhere. A series of GAO reports starting in 2007 on deaths and abuse in the industry didn’t lead to any substantive improvements, and a wide-ranging reform bill passed the House but never reached the floor in the Senate.

This time could be different. The committee report’s emphasis on reining in federal Medicaid and child welfare spending that goes to risky facilities has bipartisan appeal, even in this polarized era. Just as important, it gives Congress and federal agencies powerful new leverage – if they choose to exercise it.

Reformers and even government studies have contended for at least two decades that most troubled children would be better served by community-based care – not residential treatment. There are tools to close facilities that are not meeting standards, but Senate investigators found a culture of apparent indifference to children’s safety among state and federal regulatory agencies – something they sharply criticized.

“If you’re getting these federal dollars, nobody cares. It’s completely a Wild West.”

children’s rights attorney Amanda simmons

Current enforcement efforts are also hobbled in part by what the committee and other critics characterized as weak accrediting groups and “rubber-stamping” by agencies like The Joint Commission, a nonprofit organization that accredits and certifies U.S. health care facilities, including more than 3,000 behavioral health care organizations. Accreditation allows the facilities to become eligible for Medicaid and federal foster care funding – both lucrative revenue sources – but brings little oversight or enforcement. For instance, UHS-owned Provo Canyon, the subject of decades of complaints and lawsuits, was accredited as a psychiatric residential treatment facility.

“If you’re getting these federal dollars, nobody cares,” Oregon-based children’s rights attorney Amanda Simmons told MindSite News. “It’s completely a Wild West.”

The committee pointed to Piney Ridge Treatment Center in Arkansas where 110 incidents of physical and chemical restraint and seclusion took place in a 30-day period. Senate investigators said it was a violation of federal regulations. Not to Piney Ridge administrators, who claimed that all “restraint events” were compliant with regulations and licensing requirements. Confronted by regulators, the facility had staff members take a 10-question multiple choice test on restraint and seclusion.

The facility remains open for business, facing little more than a reprimand in 2021 following months of broken bones and restraint-related injuries, a suicide attempt and freewheeling sex between teen patients.

‘Like drinking from a firehose’

In Alabama, attorney Tommy James has filed a series of lawsuits against Vivant’s Brighter Path Tuskegee, previously known as Sequel Tuskegee, for alleged physical and sexual abuse and neglect of teenage boys. One was filed on behalf of the family of Connor Bennett, who died by suicide in 2022 after enduring “relentless sexual and physical abuse at the facility,” according to James. Another case targets the abuse and neglect of a 15-year-old boy who lived in filth and fear for his safety. And just this August, a new lawsuit against Brighter Path Tuskegee alleged that a 17-year-old boy suffered physical abuse, neglect and emotional trauma in the facility, which the attorneys dubbed a “House of Horrors.”

In court filings, attorneys for Sequel/Vivant have denied wrongdoing. The attorneys – and Vivant officials – haven’t responded to request for comment by MindSite News and outlets like American Public Media although they did tell APM in a statement that “Jay Ripley and his family formed Vivant with the goal to help youth and adult consumers of behavioral health services.”

Under Ripley’s ownership, Sequel once operated facilities in more than a dozen states. The company received hundreds of millions in Medicaid funds and tens of millions more in private equity investment, according to an NBC News investigation. Sequel has been the subject of many lawsuits and investigations by reporters and patients-rights advocates charging the chain with abuse.

At Sequel’s facility in Courtland, Alabama, teens were body-slammed against walls and floors and one boy had a nail jammed into his head after being crushed against a wall, according to a report by the federally-funded Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program.

“It’s really like drinking from a firehose. You can make money in this business if you control staffing.”

jay ripley, Co-founder of sequel and vivant

These problems did little to interrupt the flow of federal dollars to Sequel or Vivant. In a 2015 talk called “Entrepreneurship Is Fun!” first reported by The Imprint, Ripley told University of Baltimore business school student that Sequel collected $200 million in annual revenue – “mainly from the public pay side” – and had profits of more than $30 to $32 million.

“It’s really like drinking from a firehose,” Ripley said. “You can make money in this business if you control staffing.”

That’s essentially a euphemism for under-paying a small and poorly trained staff, the Senate report suggested. “By keeping staffing margins low and placements high, Ripley’s RTF business – in all its iterations – is able to profit,” the report said.

When previous reform efforts failed in the mid-2000s, the primary source of revenue for these programs were desperate private-pay parents who paid thousands of dollars each month. Now these programs don’t have as much need for affluent, frantic parents. Oregon attorney Amanda Simmons, who researched the industry for the American Bar Association, says revenue from government funding has increased significantly since the GAO first studied abuses in these programs 16 years ago.

Today, high-quality, community-based care is often impossible to find – perhaps because so much money is pouring into institutional care. That’s why a report from the National Disability Rights Network documenting the atrocious conditions in residential treatment centers called for a shutdown of programs with documented histories of abuse and for the money to go instead to community-based programs.

The failure to fund community programs has been accompanied by another flaw: the failure to target funding to the few programs proven to work. Wyden thinks funded programs should meet a reasonable, common-sense test: “It’s pretty simple: a facility should not be getting a cent of taxpayer money if it can’t prove it’s providing high-quality care.”

Failing to keep kids safe and alive

Yet even after decades of exposés and investigations, many residential treatment programs fail to meet even the most minimum standard: keeping kids safe and alive. And efforts to more effectively regulate deficient programs have frequently been ignored, often with help from indifferent or pro-industry government officials.

Those dynamics were already at work at Lakeside Academy when Cornelius Frederick showed up as a ward of the state in the fall of 2019.

Meghan Kennedy, the Lakeside case manager, said program executives cultivated a friendly relationship with the state licensing inspector – and it paid dividends for Lakeside. In one case, he undercut her effort to file an incident report about a youth with a black eye and rug burn on his face. “He would sit us down and tell us these kids lie,” Kennedy recalled. She said the inspector contended that the boy “was trying harm himself and cut himself, so they had to tackle him to get the weapon out of his hand. I didn’t believe that for a second.”

Before Frederick’s death, violence committed by poorly trained and outnumbered staff wasn’t a barrier to ambitious expansion plans. “They were taking in so much money they were breaking ground on a new dorm,” Kennedy said. Many of the kids were out-of-state referrals from Oregon and California. Both states have halted referrals in the wake of Frederick’s death – and lobbying by Paris Hilton and her allies.

While state regulations, including bans on out-of-state placements, have sometimes protected children, lax enforcement and gaping loopholes have enabled facilities to continue abusing – and sometimes killing – children.

Teenagers have been dying in wilderness therapy camps stretching back to the 1990s. When Utah passed major reforms in 2021, with the help of testimony from Paris Hilton, it limited – but didn’t end – the use of physical and chemical restraints, added funds for more regulators and required reports on use of seclusion or restraints.

But laws on their own don’t save lives. In the year following the law’s passage, two teenage girls died after alleged medical neglect at two programs, Maple Lake Academy and Diamond Ranch Academy, which had long histories of complaints and violations that didn’t lead to substantive changes. Both programs are increasingly serving children with autism, with funding from their Individualized Education Programs (IEPs).

Sofia Soto, who was on the autism spectrum, died in January 2022 at Maple Lake Academy after days of vomiting and moaning in pain. The staff ignored for days her out-of-state parents’ pleas to take her to a doctor and run tests, according to a lawsuit by her parents. A day after staff finally took her to a local urgent care facility where the doctor ran no tests, she died. The nurse who was supposed to check on her every 15 minutes fell asleep and then fabricated records about monitoring her regularly.

State officials initially promised to close the program. Then they backed off and, until moving to close it down earlier this month, kept it open – despite a social media campaign from survivors. Michael Granger, who left the program in 2016, asked the Salt Lake Tribune: “Does this mean another child has to die?” Maple Lake Academy executives haven’t responded to a request for comment, although the program denied any negligence in a reply to the family’s lawsuit.

But in late August, the news broke that the state’s famously lax Department of Licensing didn’t renew Maple Lake’s license to operate its girls’ program. The licensing department cited such incidents as a teen’s “significant injury” in a July suicide attempt and the facility’s failure to seek immediate medical help in April 2022 when a girl lost consciousness and vomited multiple times after hitting her head in a fall. The state ruled that Maple Lake must discharge its female residents by Sept. 15, but the program’s leaders announced they are appealing the decision.

Bailey, an 18-year-old girl who left the Maple Lake program in 2021, told MindSite News that she experienced cruelties there she’ll never forget. “They put a lot of people in restraints,” Bailey said. “They pushed me up against a door and pinned me so I couldn’t breathe. That can be dangerous.” Today, Bailey added, “I’m broken and afraid…I now have diagnosed PTSD as well as the depression and anxiety they sent me there to cure.”

One evidence-free approach used by Maple Lake Academy was “recreation therapy” that forced everyone – including autistic children who tried to run away – to walk around a horse barn in 100-degree heat, blindfolded. They also had to pick up heavy objects and fellow classmates, even if they hated to be touched, as detailed by V, another former resident who spoke anonymously to MindSite News.

This activity itself may have violated federal law: IEPs are funded in part by the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and are supposed to be “evidence-based.” Blindfolding autistic children in horse barns hasn’t yet been supported by research in peer-reviewed journals.

Utah’s oversight legislation also failed to prevent the death of 17-year-old Taylor Goodridge at Diamond Ranch Academy in December 2022. She died of what a pending lawsuit described as an ”easily treated” sepsis infection – but staffers ignored her pleas for help while she vomited for days before dying. State regulators initially reacted by only temporarily suspending the program. Then public outrage – and the discovery that two other youths died in earlier years – led to revocation of the program’s license in August 2023.

Now, some of the leaders who ran Diamond Ranch Academy are back. Earlier this year, they applied to open a new program for troubled teenage boys called RAFA Academy. Dean Goodridge, Taylor’s father, is alarmed. “They’re just going to do the exact same thing this time, just to boys instead of co-ed,” he told reporters in Seattle. “Just because you change the name, it’s still that facility.”

In Utah’s lax regulatory climate, such a request isn’t rejected out of hand and it was under consideration by the Utah Department of Health and Human Services, but RAFA Academy withdrew its request this May.

Utah State Senator Mike McKell, the architect of the 2021 oversight law, told MindSite News that the deaths underscored the need for tougher rules. “It’s clear that the law didn’t go far enough,” he said.

Torture, child trafficking and slave labor

But even when agencies have the right tools it doesn’t mean they’ll use them. That’s been especially clear in Alabama, where perhaps the toughest oversight law in the country was passed in 2017. It mandated licensing and inspecting of previously exempt religious programs following scandals and abuses that shocked the conscience of even hardline Christian legislators. Three leaders of Restoration Youth Academy (RYA) were sent to prison for 20 years each for felony child abuse at their program, as chronicled by this reporter in Newsweek.

Lobbying for the law was spearheaded by now-retired Prichard, Alabama police captain Charles Kennedy, who had previously investigated the academy and found horrific abuse but was unable to get his local district attorney or the state’s attorney general to prosecute. Among his findings: Restoration Academy staff hung teens upside down from the ceiling in shackles, whipped them with belts and forced a depressed teen to sit naked for days in an isolation cell. Kennedy said that program’s manager, William Knott, at one point urged the 14-year-old boy to kill himself with a gun Knott handed him. The boy pointed the gun to his own temple, and then, he later told Kennedy, “I pulled it, and it went click.”

Today, even after passage of the law, programs like Vivant Tuskegee continue to be accused of abuse and wrongful death – and Charles Kennedy remains outraged at state agencies for their failure to protect vulnerable children. “It’s not going to be enforced,” he told MindSite News, because Alabama’s Department of Human Resources “is as worthless as tits on a bull.”

Perhaps this could be written off as an unwelcome feature of an anti-regulation Republican state. But federal agencies in the Biden administration are also failing on enforcement. At the Senate hearing in June, a GAO official pointed out that Health and Human Services hasn’t even followed a modest recommendation from the watchdog’s 2022 report: Share best practices with the states to prevent and address youth maltreatment in residential treatment programs for children and youth.

The report calls for a number of crucial steps to immediately improve residential treatment centers and the closing of facilities that endanger children. But it apparently has not worried troubled teen industry executives. “We haven’t seen any real impact from the Senate hearing,” Acadia CEO Christopher Hunter said in an Aug. 1 earnings call. Regulators “understand our facilities are providing high-quality care to this population.”

The Senate investigators clearly don’t think so. The report notes that sending distressed children to live in remote treatment centers leaves their needs unaddressed and causes enormous suffering.

“Their lives are ending before they even begin – systematically, by design,” the report says. “The warehousing of these children in RTFs only remedies society’s disinterest in addressing their needs…It is imperative to imagine, and help create, a real world with a place for these children, with the support they need, alongside their communities.”

At its core, the Senate report is a call for regulators to use their authority to protect a vulnerable group – children – from powerful companies and institutions. One tool they could employ is described in a buried footnote in the June GAO report. “HHS’s oversight role includes the authority to cancel state approval of (psychiatric residential treatment facilities) that do not meet federal health or safety requirements,” says footnote #28.

“We don’t even need a Presidential executive order,” said one Senate Finance Committee staffer. “The agencies just need to be enforcing the current laws.” And to the shame of the nation, they are not.

This story was reported and published with support from the Commonwealth Fund.

Journalist Art Levine is an investigative reporter and the author of Mental Health Inc: How Corruption, Lax Oversight and Failed Reforms Endanger Our Most Vulnerable.

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.