Different Ways to Understand the Loneliness Epidemic

Good Wednesday morning! The loneliness epidemic is both unbelievably complicated and incredibly simple – and it’s also worsening our class divide. Broad dispensing of naloxone by pharmacies without a prescription reduced overdose deaths. A father’s search for a son who didn’t want to be found.

Plus: Most psychiatric clinicians listed in directories as accepting new patients were not (or had out-of-service numbers). And more.

Bonus: The psychedelic brew ayahuasca seemed to be helping Israeli-Palestinian peace activists heal from intergenerational trauma in this episode of the Altered States podcast. Then the region erupted into chaos and violence.

Why is the loneliness epidemic so hard to cure? Or is it?

Most experts still use a definition of loneliness that was coined in the early 1980s: “a discrepancy between one’s desired and achieved levels of social relations.”

I vividly remember when that discrepancy became a defining feature of my life. In 2018, I had just left a large newsroom full of people I’d worked with for 30 years and started a new job in a newsroom full of people I’d never know because the job was remote. We didn’t even have Zoom meetings – the three gigs I’m working now don’t either. My world is dramatically smaller.

Remote work is one culprit in the growing loneliness epidemic, according to a New York Times Magazine story headlined “Why Is Loneliness So Hard to Cure?” But the solutions often proposed – join a club, spend quality time with friends, go back to a time when we were all more connected – reflect a misunderstanding of how we live now and will live in the future, journalist Matthew Shaer writes: “When we talk about loneliness, what we’re actually talking about are all the issues that swirl perilously underneath it: alienation and isolation, distrust and disconnection and above all, a sense that many of the institutions and traditions that once held us together are less available to us or no longer of interest.”

Shaer’s story is a guide to the history, science and thinking about loneliness. We learn that, compared with problems like anxiety and depression, which are believed to have afflicted humans through recorded time, people were not always lonely in the ways that contemporary experts understand the emotion today. It was hardly discussed in the West until the 1820s, according to a database of words in English-language works, when war, mechanization, and the rise of cities upended how people lived. It is also cyclical: Anxiety about loneliness went up in the early 1900s, when everyone started listening to the radio, and again over worries that cars would lead drivers away from their families. Of course, the COVID-19 disruptions were more real, if – in theory – temporary. Shaerer predicts that today’s loneliness crisis will turn out to be “a mass period of acclimatization,” during which “we make our peace with certain tradeoffs and realities.” Like Facebook friends, and romances that are partly online and partly off.

I don’t agree. I found Times opinion writer David French’s column, “The Loneliness Epidemic Has a Cure,” more persuasive. It focuses on the surprisingly sizable role that loneliness plays in our national divides and stagnant social and economic mobility – and suggests one way to improve them: “Make a new friend.” (Scaling up will be a challenge.) Surgeon General Vivek Murthy cites some disturbing data in his 2023 advisory warning of an American “epidemic of loneliness and isolation,” but the statistics cited by French are clearer and more worrisome. Here’s one: Between 1990 and 2024, the percentage of college graduates who reported having zero close friends rose a lot – from 2% to 10% – while among high school graduates, the percentage increased 3% to 24%, a rise that French calls “heartbreaking.”

“Tens of millions of working-class Americans experience a social reality different from that of their more educated peers,” he writes. There is a “class divide,” he adds, in the number of Americans who can rely on someone to lend them a small amount of money or give them a ride to the doctor. As a result, lower-income Americans report a far lower sense of belonging than those who are wealthier. His prescription, however, doesn’t go much beyond making friends and engaging with your neighbors.

Still, I’m indebted to French for helping explain to me as a college-educated person some of the Trump phenomenon and the benefit it provides to his biggest fans: a powerful sense of connection and belonging (even if much of that spirit is built on stoking resentments and denigrating others). They come for Trump and stay for the relationships developed at rallies with raucous party vibes, nurtured as many of them travel the country together, staying at one another’s homes, sharing hotel rooms and car-pooling. I know that feeling. More than 50 years ago, I was repeatedly immersed in huge crowds of strangers who were soon to be friends, drawn together for a cause we passionately believed in: ending the Vietnam War. It was the least lonely I’ve ever felt, and I miss it.

Pharmacy ‘standing orders’ for naloxone made a difference

Overdose prevention is a tricky business. A lot of strategies have been tried, but clear evidence of success is often elusive. Even the effectiveness of naloxone, the overdose reversal medication that has saved so many lives, is impossible to accurately measure. No one knows how many of those who’ve been revived would have gone on to die without it.

A gold-standard clinical trial would require giving naloxone to some people who are overdosing and withholding it from others, which is obviously unethical. But enough time has passed that the impact of public policies involving naloxone can be measured too, and in real life rather than a controlled trial.

The FDA approved over-the-counter naloxone in 2023, but when the epidemic of overdose deaths first reached the public’s radar screen 15 or 20 years earlier, using a medication to reverse overdoses was a radical idea – “let them die” may have been a more common sentiment. Its availability was limited to emergency departments and first responders, plus harm-reduction programs that often operated underground. As the overdose death rate grew rapidly, so did interest in making naloxone more accessible. Many states started issuing “standing orders” – a sort of blank prescription that third parties could use (you can’t give yourself naloxone while in the throes of an overdose), making the medication easier to obtain. Massachusetts was one of the first states to issue them.

For a study published in JAMA Network Open, a team of researchers analyzed naloxone dispensing data over 24 quarters (spanning before and after the first standing orders took effect) from pharmacies in all 351 Massachusetts municipalities. They adopted standing orders at different rates, and the study compared them over time with opioid overdose fatality rates in each jurisdiction.

The results showed a significant downward slope of opioid fatality rates over time in the 241 cities and towns that dispensed standing-order naloxone by the end of the study period in 2018, compared with those that did not. Community dispensing of naloxone was associated with a “relative, gradual, and significant decrease in opioid fatality rates,” the authors concluded.

Could a father’s love be enough to end his son’s homelessness?

Father and son had once been close. In Seattle, from the time his son was small, Bob Garrison said, they would camp under the stars, talking about time and space and the cosmos. Robert – eventually grown to 6 feet, 6 inches and “a teddy bear,” his mother said − was always shy and socially awkward, but he graduated high school, had a career and supported a family. Then, in 2013, came blinding headaches. Doctors found an aneurysm; the surgery seemed successful. But Robert had changed, his father said. He had never shown signs of serious mental illness before, but now he was withdrawn and sometimes paranoid, like “a switch would get thrown,” Bob told the New York Times. About three years ago, “he had an episode where he thought he had died and a blinding light came down and entered his body,” his father said. Robert became obsessed with religion and stopped going to work.

But he always stayed in touch with his family, who loved him deeply, sometimes asking his parents to send small amounts of money digitally for food and emergency shelter. Then, in March, Robert suddenly stopped answering his father’s texts, and his calls went straight to voice mail. Worried, and then panicked, Bob Garrison began calling hospitals and the coroner’s office and everyplace he could think of. He discovered that Robert had taken a train to Los Angeles. After a couple of possible sightings at a beach and an illegal campsite near San Clemente, he flew down. And he spotted him: a tall, ragged figure with a long beard sitting on a bench on a pier, with an open Bible, gazing out at the ocean.

Bob, 70, sat down next to his son, 45. “Put my arm around him. Pulled him tight. And I said, ‘We’ve been looking for you.’” They went out for Mexican food. Robert agreed to come back to his parents’ home 100 miles southeast of Seattle. It didn’t go well. Instead of agreeing to see a doctor, he asked his father to drive him into the city.

Robert spoke with a Times reporter four days after his father dropped him off. He told a similar life story, up until the moment in 2021 when “the light touched me and healed me and changed me” during what he believes was a cardiac arrest. “My father thinks I need treatment but there’s nothing wrong with my mental health − he just doesn’t believe me,” he said. “He thinks this is all cults and charismatics.”

When his father found him on the pier, Robert told the reporter, his heart sank: His assignment was “compromised” because his location was now known. He had not been afraid or alone, he said, citing Scripture, “for every hair on your head is accounted for by the Lord.” He went back south to San Clemente a few days later. When Bob committed himself only months before to finding his son, he’d wondered whether homelessness could be solved simply with enough love. Now that seemed naïve, he told a reporter, and he had no answers about what, if anything, to do next. “I gave it my best,” Bob wrote in an email. “Sometimes your best just isn’t good enough.”

In other news…

About 22% of people who died of a drug overdose also had mental illness, according to an analysis of records for half the 108,000 U.S. overdose fatalities in 2022 published in CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Undiagnosed conditions would almost certainly raise that percentage. The most common disorders were depression (13%) and anxiety (9%). The authors noted that for about 25% of overdose victims with diagnosed mental illness (compared to 15% without), there had been, in the month before their death, at least one potential opportunity – in emergency departments, urgent care facilities, prisons, jails, and treatment programs – to intervene and provide overdose prevention services. They recommended exploring the availability and expansion of substance use screening, treatment, referrals or linkage, and harm reduction services within those settings.

How many psychiatrists in Medicaid managed care listings truly have openings? Not many, according to a study in JAMA. Researchers conducted a “secret shopper” study. Posing as Medicaid enrollees asking for the next available appointment, they randomly called clinicians in four large cities who were listed in the directories of Medicaid managed care organizations as accepting new patients. The results: just 27% had appointments available, and it varied by city. In New York, they were able to get an appointment with a clinician 36% of the time (median wait time: 28 days). Other cities were even worse, with appointments booked 30% of the time in Phoenix, 28% of the time in Chicago, and just 15% in Los Angeles, where the median wait was a whopping 64 days. Among the 263 clinicians with whom appointments could not be made, 15% had a listed number that was incorrect or out of service and 35% didn’t answer the phone on two attempts. Also worth reading: a ProPublica report on how insurers make it hard to find a therapist who accepts insurance, summarized in last Tuesday’s MindSite News Daily.

Transgender adolescents are more likely to find helpful adults in school than their cisgender classmates, according to a finding from a Wisconsin survey published in JAMA Pediatrics. Other results were more typical, and disturbing: Trans students were two to three times as likely as their cisgender classmates to be bullied, skip school because they felt unsafe, and feel like they didn’t belong at school. They also reported 50% more anxiety and two to three times the risk of depression, self-harming behavior, and suicide thoughts or attempts. On the other hand, they were considerably more likely to be able to identify at least one adult in school they could talk to compared with cisgender peers. This and other results of the analysis led the authors to write that “adults in schools play a differentially greater role, and parents play a smaller role, when depressed or anxious transgender vs cisgender youth seek help.”

If you or someone you know is in crisis or experiencing suicidal thoughts, call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline and connect in English or Spanish. If you’re a veteran press 1. If you’re deaf or hard of hearing dial 711, then 988. Services are free and available 24/7.

Recent MindSite News Stories

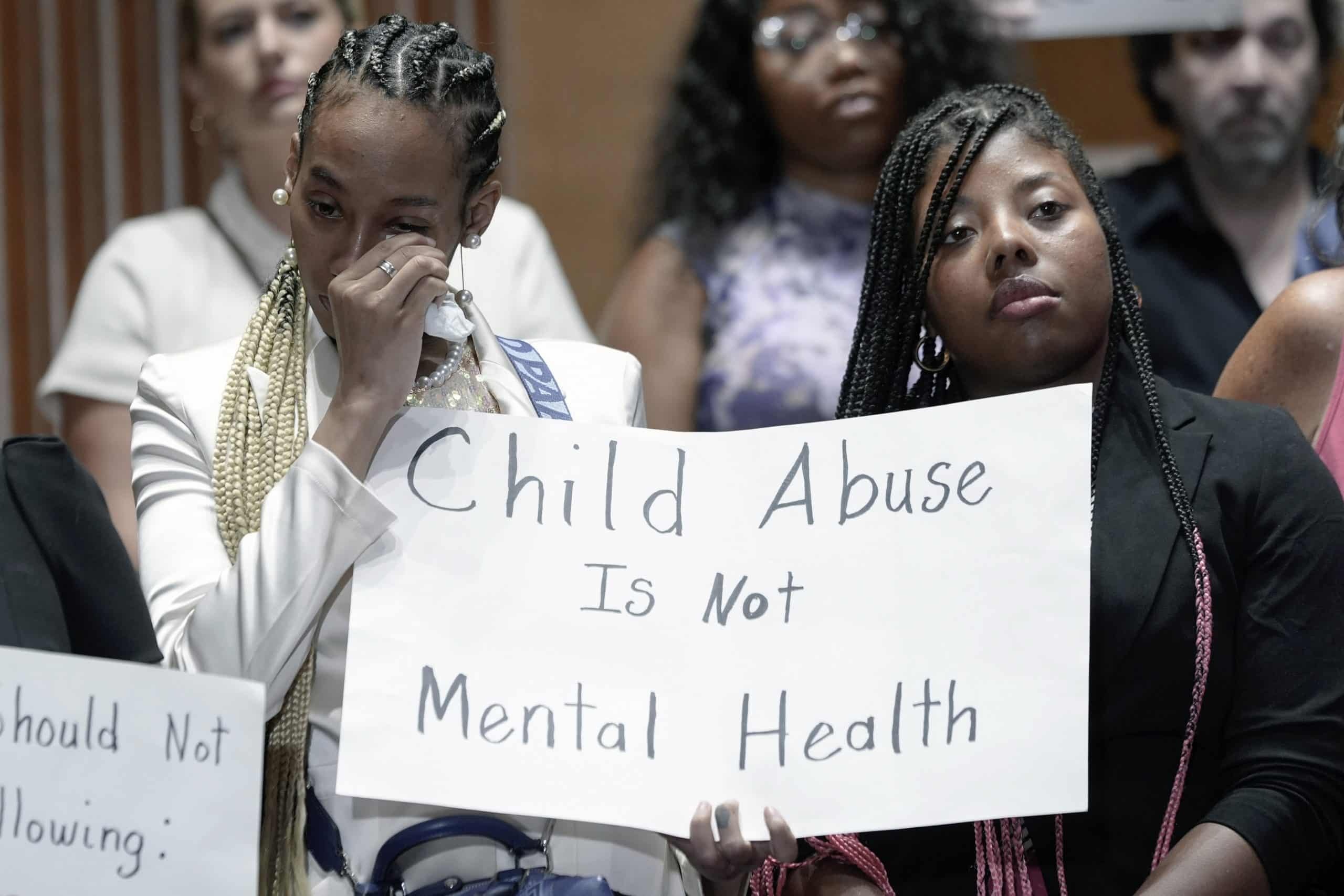

How Paris Hilton and Other Survivors of the Troubled Teen Industry Unleashed a Movement

Meet Five True-Life Avengers Who Are Holding the Troubled Teen Industry Accountable.

Troubled Teen Industry Is ‘Taxpayer-Funded Child Abuse,’ Senate Report and Paris Hilton Say. Where Are the Government Regulators?

Physical abuse, rape, and emotional trauma is endemic to psychiatric residential treatment centers for kids and youth nationwide.

That Crisis of Mentally Ill People Languishing in Jail? It’s Even Worse Than We Thought

The number of mentally ill people held in jails for weeks or months awaiting competency hearings is rising. Experts call it a crisis.

If you’re not subscribed to MindSite News Daily, click here to sign up.

Support our mission to report on the workings and failings of the

mental health system in America and create a sense of national urgency to transform it.

For more frequent updates, follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram:

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.

Copyright © 2021 MindSite News, All rights reserved.

You are receiving this email because you signed up at our website. Thank you for reading MindSite News.

mindsitenews.org

Mental health can't wait.

America is in a mental health crisis — but too often, the media overlooks this urgent issue. MindSite News is different. We’re the only national newsroom dedicated exclusively to mental health journalism, exposing systemic failures and spotlighting lifesaving solutions. And as a nonprofit, we depend on reader support to stay independent and focused on the truth.

It takes less than one minute to make a difference. No amount is too small.

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.