Dissociative Identity Disorder Through The Ages

From the Renaissance to the controversial book Sybil and beyond, the existence of multiple personalities has been explored for centuries.

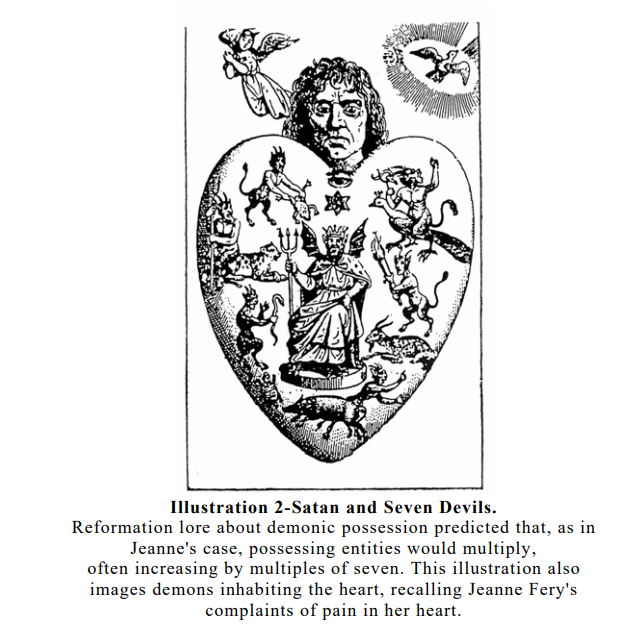

The first documented case of what is now called dissociative identity disorder dates to 1584. In France , a 25-year-old Dominican nun, Jeanne Fery, displayed erratic behaviors, including violence, head-banging, attempting to cut and eat her own flesh and trying to strangle herself. This led her religious community to believe she was possessed. Fery had both protective and destructive alter identities, which she said included a number of demons as well as Mary Magdalene as a protector. (The nomenclature of “alter identities” is still used today.)

Jeanne Fery and her exorcists at the convent and elsewhere wrote in great detail about her illness and largely “successful” exorcisms. Her treatment plan also included journaling. From her accounts, contemporary historians have deduced that, like most people with DID or multiple personality disorder, she had suffered severe childhood trauma: She was cursed by her father at age two, beaten mercilessly as a little girl, and was reportedly sexually abused by him.

But Fery was largely forgotten about until 1886 when neurologist Dr. Désiré Bourneville diagnosed her post-mortem with dissociative identity disorder and re-published her memoirs, which included details of the severe beatings and other traumatic events she suffered during her childhood.

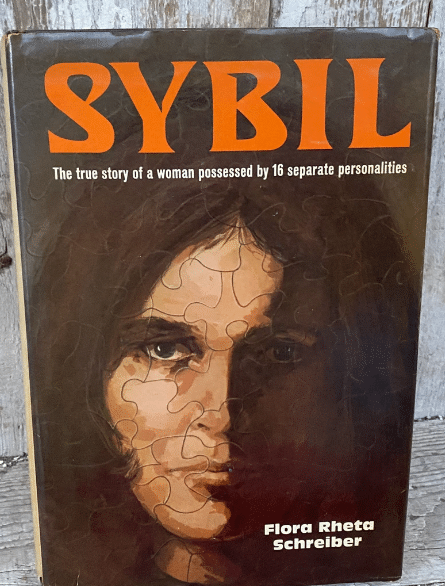

Today the medical history of dissociative identity disorder is interwoven with its media representation. A landmark of multiple personality disorder and DID’s popularization was the 1973 publication of the book Sybil: The true story of a woman possessed by 16 separate personalities, written by Flora Rheta Schreiber.

Sybil Dorsett, whose real name was Shirley Ardell Mason, studied at Columbia University at the time she first sought help from Freudian psychoanalyst Cornelia B. Wilbur. Wilbur went on to treat her for 11 years, a total of 2,354 office sessions.

Wilbur’s methods would be considered unethical today but were mainstream in the 1950s. She prescribed Sybil a laundry list of psychoactive medications: Daprisal, Equanil, Demerol, Dexamyl, Seconal, Ritalin, and Thorazine – an antipsychotic that can cause side effects including confusion, restlessness, and, in serious cases, worsening psychosis.

Wilbur also reportedly used unmodified electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), passing electricity through Sybil’s brain to induce grand mal seizures and treat some of her symptoms. (The therapy is still used today, but patients are administered muscle relaxants and put under anesthesia.) In the case of Sybil, the most serious side effect was thought to be short-term memory loss.

Most of Sybil’s therapy revolved around hypnosis, facilitated by injections of Pentothal. The drug was nicknamed “truth serum,” and used by anesthesiologists and psychiatrists to treat acute anxiety during psychoanalysis. During the second half of the twentieth century, Pentothal acquired a controversial reputation as it was used to induce coma for euthanasia and was associated with Cold War espionage. Psychiatrists administered it to facilitate the retrieval of traumatic repressed memories. The drug was also thought to make patients highly suggestible.

Psychoanalyst Wilbur said she aimed to retrieve all of Sybil’s repressed memories to integrate her 16 personalities and make her whole again. Schreiber’s book about the case sold over six million copies in the U.S., and its subsequent 1976 television adaptation was broadcast to a fifth of the American population. (The rare diagnosis was then called multiple personality disorder.) When the book was published, fewer than two hundred cases worldwide were reported in the medical literature.

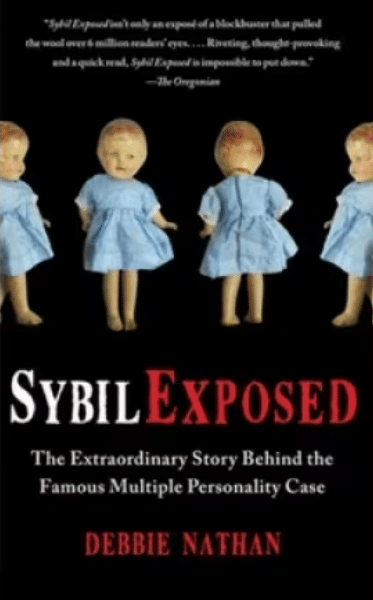

In 1980, multiple personality disorder was recognized as an official psychiatric illness. Soon thereafter, “mental health practitioners in America were diagnosing thousands of cases a year,” wrote journalist Debbie Nathan in Sybil Exposed: The Extraordinary Story Behind the Famous Multiple Personality Case.

Nathan’s book, published in 2011, shed a different light on Sybil’s case. She revealed – and the real Sybil confirmed – that Shirley had created her first alternate identity to get more attention from Wilbur. Nathan also said that some of Sybil’s alters were suggested by Wilbur, her psychoanalyst, who diagnosed her patient with multiple personality disorder and developed a plan to publish a book about her. At that point, Shirley began churning out more and more alternate identities, although she finally wrote to Wilbur that she had been making them up. By that time, Wilbur was too invested in the case to let go.

Wilbur “fed Sybil, gave her money, and paid her rent,” Nathan wrote. “After years of this behavior, the archives revealed, the two women developed a slavish mutual dependency upon each other. Toward the end of their lives they ended up living together.”

Nathan also found that Shirley (Sybil’s real name), Wilbur, and Schreiber, the author of Sybil, all profited from the case. They created an enterprise, Sybil Incorporated, and split all profits from Sybil movies, board games, tee shirts, dolls and a musical.

Cases like this “actually end up affecting the law, affecting mental health, affecting political decisions,” Nathan said in a New York Times documentary. “The stuff that sounds the most dramatic and the most credible at the same time is probably the most dangerous.”

While Sybil’s story turned out to be a hoax, dissociative identity disorder is a real condition. In 1994, the “multiple personality disorder” was replaced as a diagnosis by “dissociative identity disorder” to highlight that patients suffer from episodes of dissociation, usually triggered by severe childhood trauma.

Real cases of dissociation are typically short, rare and unlikely to affect someone’s ability to function socially or on the job, wrote Dr. Marlene Steinberg in her book The Stranger in the Mirror: Dissociation – The Hidden Epidemic. But dissociation becomes problematic if the episodes are “persistent, recurrent and disruptive,” she wrote.

That was the case for Olga Trujillo, a 61-year-old woman who was diagnosed with DID at age 31. She recounted the repetitive sexual abuses perpetrated by her father in her memoir The Sum of My Parts.

“Being able to watch the attack as if it were happening to someone else helped me feel calmer and safer,” she wrote, about the first time she was raped, at 3 years old.

To survive, she created a house in her mind and stored this traumatic memory in one of the rooms. “I closed that door, and I painted it black, and I locked it,” she said. Every time Trujillo’s father sexually abused her, she created a new room to contain the memory. There were happy rooms as well, painted yellow. Those remained open so she could draw from them feelings of happiness and safety. By the time she reached adolescence, her identity was shattered into fragments.

What Trujillo refers to as “rooms” or “fragments” are also called personality states, multiples, identities, or alters. People with DID do not have several persons living inside their head affliction is subtle, not movie-like: They do not develop a cohesive sense of self.

Trujillo’s fragments are very much different aspects of herself as an individual. “It’s not different people,” she said. “This is all parts of me.”

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.