TikTok Posts on the Rare Illness Known as Dissociative Identity Disorder Has Exploded Among Teens. What’s Behind the Fixation?

Some researchers suggest healthcare providers should create more engaging content on #DID TikTok channels to counter misinformation.

The first time Fennic remembers leaving their body, they were 11 years old. Lying on their bed, they were feeling suicidal, sobbing, and contemplating self-harm when suddenly they heard a female voice whisper inside their head: “Hey, it’s okay. I’m gonna take over now.”

Fennic, who is now 20, felt as if they were stepping back from their body while somebody else was coming forward. When they regained consciousness, objects had been moved around the room. They checked their phone. Hours had passed.

In a panic, they contacted some online friends they had made on the group-chatting platform Discord, who had been posting about their experience with dissociative identity disorder (DID), known in decades past as multiple personality disorder. At first, Fennic worried of having been influenced by all the DID content on Discord. But the online friends they spoke to were adamant: Fennic’s symptoms, they said, “sound a lot like DID.”

Fennic still has not been officially diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder – but when we spoke, they were convinced that they probably had it. “I’m in the process (of finding out),” they said. “I’ve been working with my therapist.”

In the meantime, Fennic is one of many young people who believe they have DID and have taken to TikTok to share their experience in posts that reap billions of views. They have introduced viewers to their seven “alters” – the different identities that exist within the same person – which include Neo, Sky, Lux, Liam, and, of course, Fennic.

Fennic’s postings reflects TikTok’s canons: Snappy transitions and evocative captions accompanied by trendy tunes. They share having been “mentally and emotionally abused” by their parents, encourage their community to find solace in themselves and express their frustration at TikTok’s algorithm: “tiktok i need your help. I have almost 300k followers and no one is even seeing my videos anymore please i’m begging you all to just push buttons.”

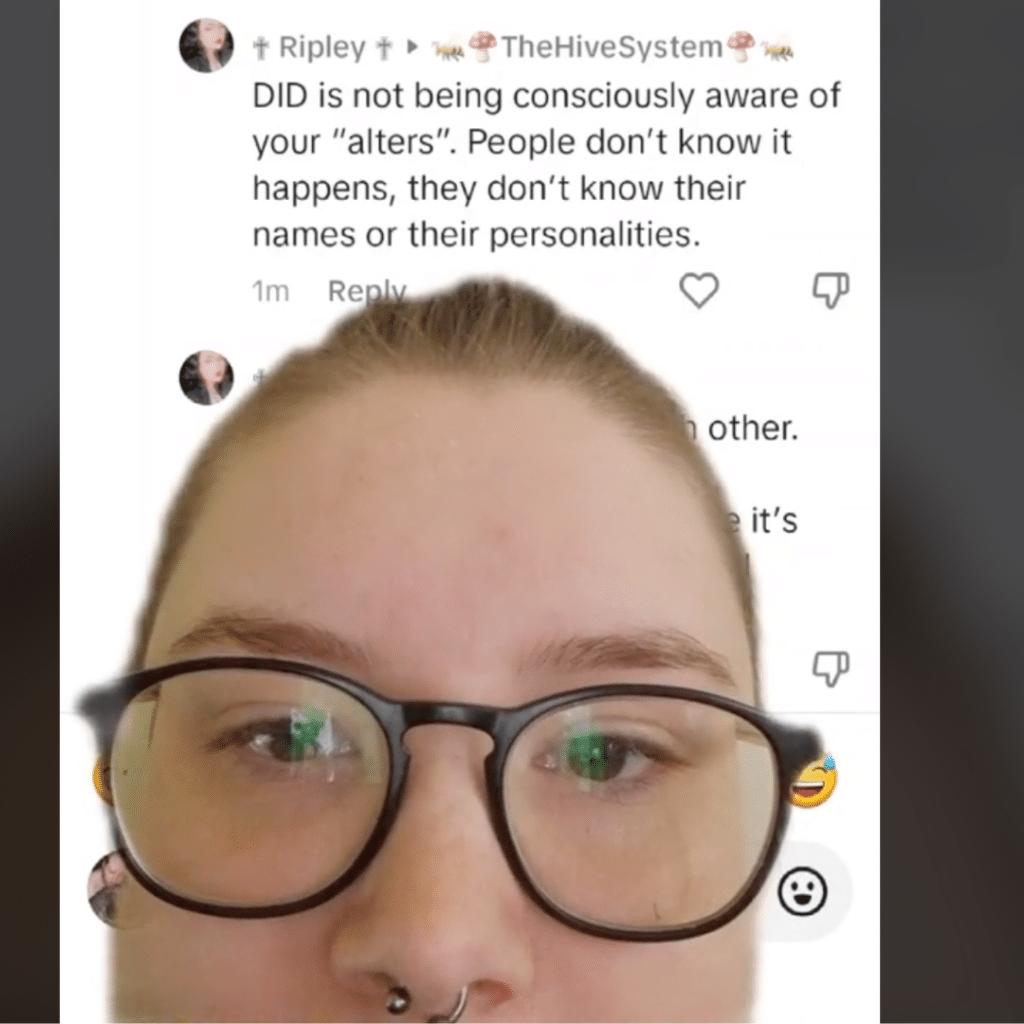

Although Fennic was content to simply seek counsel and support from their online counterparts, some people in the TikTok DID community have warred with scientists when challenged.

Richard Baer, a Chicago psychiatrist who has treated patients with DID and is the author of Switching Time: A Doctor’s Harrowing Story of Treating a Woman with 17 Personalities, is skeptical of the DID wave on TikTok. For people who actually have the disorder, “their dissociative states are normal life,” Baer said. “It’s really unusual for a DID patient to present themselves saying, ‘I think I have DID.’” Instead, they usually knock on the therapist’s door because of crippling anxiety, bone-chilling depression or unsettling memory gaps.

But given the rareness of the condition – a 2011 literature review cited prevalence estimates among the world population ranging from 0.4% to 3.1% – why is DID so prevalent on TikTok?

DID’s explosion on social media during the pandemic

Like other diagnoses of mental illness, including narcissistic personality disorder, DID exploded on TikTok during the pandemic. Videos and posts featuring the hashtag #DID number in the millions and have chalked up billions of views. Related hashtags such as #didsystem gather billions more.

As explained in the newest version of psychiatry’s diagnostic bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-5-TR, a patient with DID finds their identity split into two or more personality states, which alternatively take control of their behaviors, thoughts and feelings. The disorder functions as a mechanism of self-protection designed to help people cope with severe trauma, according to the manual, and “may be described in some cultures as an experience of possession.”

While DID is considered a rare disease, at the higher end of its estimated prevalence it is more common than schizophrenia. Some experts believe the actual number to be higher because the condition often goes undiagnosed. But the billions of views that DID is getting on TikTok – and the inordinate number of youths who self-identify with the disorder – has attracted skepticism both online and off.

Experts such as Baer question whether the illness’ portrayal on the platform is an atypical clinical presentation, a case of mass contagion or simply an act. Others wonder whether the TikTok portrayals are ones featuring a small number of posters who actually have DID, accompanied by a larger group of users who are convinced they have DID and a few who are exploiting the niche to foster a fertile (and occasionally somewhat lucrative) terrain for views, likes and follows.

“Tiktok i need your help”

Fennic started posting about their experience with DID on TikTok in 2021. They refer to themselves as “we” since their multiple alternative personalities, or “alters,” appear to interact in an orderly and organized “system,” a pattern that some TikTokers also describe as “plural” – a term that “encompasses all experiences of being, or having, more than a single individual within a single body.”

When we corresponded in 2023 and again in 2024, Fennic was part of a large community of DID patients who share their experience on TikTok. These users often identify by the name of their “system,” composed of multiple alters. (Fennic was excited to be part of an article on TikTok DID channels but recently removed their content and have not responded to recent emails.)

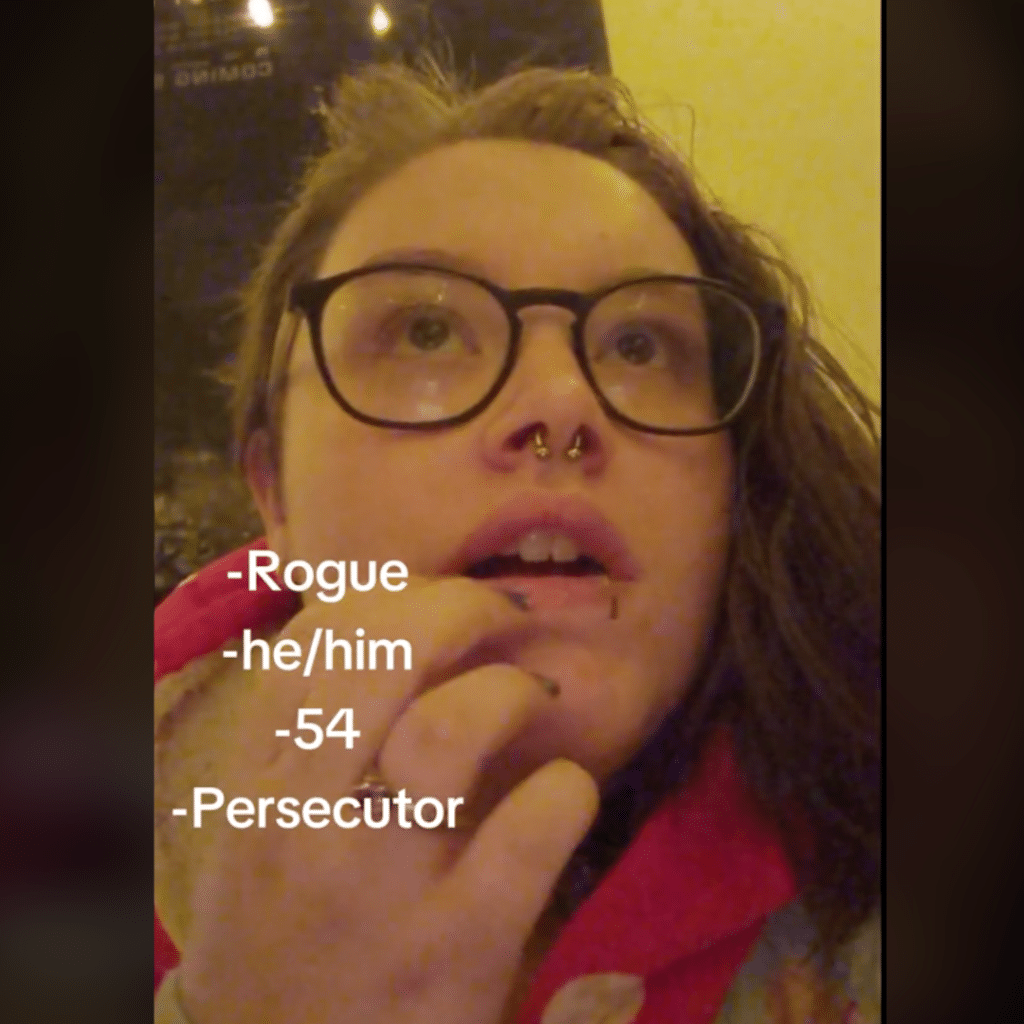

On Tiktok, users in the #DID community users often identify by the name of their “system,” composed of multiple alters, or alternative identities.

One TikTok persona who posts as the Hive System claims 27 alters, one of them named Bee. In an interview with me, they compared having different identities to monitoring a control panel inside their brain. All of them have a different role and response to triggers.

“If I was out in a dangerous situation, I would freeze, I wouldn’t know what to do. Whereas Chaos (one of their alters) knows exactly what to do, he would go straight to defense. And if it was Ben (another alter), he would think logically about the situation and try to defuse the situation,” Bee told MindSite News.

Although DID belongs to a large family of dissociative disorders listed in the DSM-5, including depersonalization disorder and dissociative amnesia, it attracts on TikTok an unsettling, and at times voyeuristic, focus.

“A disorder of hiddenness”

Dr. Andrea Giedinghagen, a pediatric psychiatrist at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, is not convinced most DID sufferers on TikTok actually have the disorder. “DID is a disorder of hiddenness,” she said. She wonders why patients who live with it would advertise it on social media.

Baer agrees. “It’d be unusual for a DID patient to exhibit themselves on social media because DID is a defense against trauma. So I think most DID patients would be protective of themselves and not exhibitionistic about it,” he said.

Indeed, patients with DID report higher levels of abuse and neglect, according to several epidemiological studies. The main function of dissociation is to cope with stressful situations. In fact, most people will experience a dissociative episode in their life. Survivors of car crashes, for instance, may report feeling like time had stopped as the car was spinning out of control. Patients who had near-death experiences can remember floating above their bodies, looking at the scene. But people with DID tend to have regular episodes of dissociation.

“If I was out in a dangerous situation, I would freeze, I wouldn’t know what to do. Whereas Chaos knows exactly what to do, he would go straight to defense.

Bee of the hive system, discussing their alters

Some TikTok accounts, however, suggest their posters are unfamiliar with true DID, especially those featuring alters that rapidly switch in front of the camera. “I can feel it coming up,” says Iris, whose Tik Tok bio says they were diagnosed with DID. A name tag that spells ‘Iris’ adheres to their shirt. They close their eyes and drop their head forward until it rests on the table. The caption “*No one in the body*” appears on the screen. Eight seconds later, they awake and raise their head, displaying a different tic-like demeanor. With a smirk, they tear off the name tag: “Guess the player,” they say. Iris is gone. Now appearing, says a note on the screen, is Jonas, one of their 110 alters. Since the influencer – whose account is called The Sprite Company – stopped posting in September 2022, comments have multiplied under their videos accusing them of faking DID.

Some users have questioned whether people posting about DID actually have schizophrenia or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). But DID is different from the other two disorders, said Paul Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry, medicine and law at Columbia University.

“People with schizophrenia experience things coming at them from outside, voices telling them they’re bad people or what they should do, or delusional concerns that other people are trying to harm them,” he told MindSite News. “But their sense of self, that they are a unique individual, typically remains intact.”

And while some people with PTSD do experience dissociation, PTSD does not alter the patient’s sense of self. Even if a person with PTSD finds themselves back on the battlefield when they hear fireworks, they would still recognize themselves in the mirror.

“You retain a sense of continuity of yourself, who you are. I’m a physician, I’m a psychiatrist, I have a family, I have a history, where I went to school, where I lived, who my friends are,” said Appelbaum.

But although amnesia may not be part of a PTSD diagnosis, it is a criterion for dissociative identity disorder – and some TikTok users on DID channels may indeed have symptoms of the disorder. Alex, who has been on a TikTok DID channel since February 2021, says they are part of a system of 97 alters. Blackouts plagued their childhood. Memories their friends share from primary school are forgotten. The way they spent their day? They’re usually unable to recall. “I always told myself it wasn’t a big deal. I thought I was tired,” Alex told me.

Another TikTok user, Havapsy, echoed Alex’s experience. As they recounted to me, they remembered running into a friend who asked why they did not come to their party the previous Saturday. They had no recollection of ever having been told about a party. But several friends confirmed Havapsy had been attending weekly get-togethers at their place for months. They would also call them by another name, declaring they had told them to do so. “My first thought was: This can’t be. They must be dreaming,” said Havapsy.

But for all the people on TikTok who have DID – or sincerely believe they do – there are some who are joining in for other reasons. Beginning in 2021, a rash of anonymous confessions have been posted on TikTok and other mediums from people who said they were ‘faking’ DID for fun, attention or to escape responsibility for certain actions. One “27-ish” user called himself a “recovered DID faker” who said he had been pretending to have DID for more than a decade.

Loneliness among teens and youth, which has been called an epidemic by the U.S. Surgeon General and soared during the pandemic, may also underlie the rise of DID content online — especially among groups that tend to suffer from bullying and prejudice.

“So why did I fake DID?” asked a post from another pretender who began faking DID on Tumblr. “Simple – I wanted attention and deniability. Anyone who disagreed with me was an ableist or was bullying me because I was a queer minor. I was free to be erratic and hostile and I pinned it on an alter. I loved the attention, both good and bad… I painted myself as the victim because it got me attention and community.”

_____________________________

In a 2011 memoir about her experience with dissociative identity disorder called The Sum of My Parts, Olga Trujillo writes about years of rape and abuse at the hands of her stepfather starting at age 3. This trauma led her to create alternate identities for herself where she could confine her terrible memories behind different doors and lock them. (For more on Trujillo, see my sidebar on the cultural history of DID, which also examines the bestseller Sybil that told the dramatic – and false – story of a woman with what was then called multiple personality disorder).

Trujillo exemplifies the trauma model of DID, as opposed to the fantasy model. The trauma model is accepted by most mental health professionals and scientists; the latter, embraced by a minority, postulates some people with DID are highly suggestible and confabulate false trauma memories, or fantasies. “DID is predominantly due to suggestion and enactment and is facilitated by high levels of fantasy proneness and suggestibility,” according to an article published in 2021 by The British Journal of Psychiatry. It proposes that memories of trauma in DID patients are created, suggested to, or exaggerated by patients.

While this theory has been debunked, most recently by a 2012 review that examined the evidence base for the two models, some researchers warn that fantasy and unconscious motivation are playing a role in the boom of self-diagnosed DID cases on social media.

Among them is Dr. Matthew A. Robinson, program director of the Trauma Continuum of Care at McLean Hospital, specializes in treating trauma and dissociative disorders. In February 2023, he gave a lecture about social media’s self- diagnosed DID frenzy. “Social media and online platforms, including TikTok, YouTube, Instagram, and so on, have ballooned with DID-related content,” he said. “Most of the time, there are gross myths or misrepresentations of DID, and inaccurate self-pathologization and inaccurate self-diagnosis.”

So why did I fake DID [on TikTok]? Simple: I wanted attention…I loved the attention, both good and bad. I painted myself as the victim because it got me attention and community.

Post from an anonymous ‘recovered DID faker’

Drawing on other researchers’ work on “imitated DID,” he explained that patients can simulate, sometimes involuntarily or unconsciously, the illness for psychological and social gains. “It can help with labeling of feelings, or emotional states that might seem extreme or out of control,” said Robinson. “It can create meaning out of suffering from a sense of emptiness, and it can help avoid feelings of guilt or shame. Therefore social media platforms are ideal places for imitated DID to thrive.”

Even some DID influencers point to red flags. The TikToker who dubs themself Havapsy, for example, is wary of tweens whose alters are well-defined. “A person’s identity is constructed during their adolescence. So it doesn’t make sense to have fully formed alters that young,” they said. “But you never know, so I would never call them out in the comment section.”

Whether DID can be faked in “real life” is also a contentious topic. Richard Baer has treated three patients with DID over three decades of practice and believes that faking the disorder for years would be “hard to keep up even for the very talented.” He recalls one patient being treated by a colleague who pretended to have more than 100 personalities. Following a six-month hospitalization, she admitted to having lied to please him.

Appelbaum disagrees that it is hard to keep up a front of DID. “Any psychiatric syndrome and some non-psychiatric medical syndromes can be simulated,” he said. “Could a good actor persuasively fake DID? Sure, just like a good actor can fake their personal history.”

As part of a webinar, Robinson played clips found on TikTok to illustrate DID presentations that were not consistent with his clinical experience. Videos of quick switches from one alter to the other piqued his interest. “Switches we see in genuine DID – when we see them – are subtle, often unnoticed by outside observers,” Robinson said. Most experts also agree that switches cannot be controlled because they are triggered.

Whether unconscious or not, simulated DID “can help with labeling of feelings or emotional states that might seem extreme or out of control. It can create meaning out of suffering from a sense of emptiness… Therefore social media platforms are ideal places for imitated DID to thrive.”

Dr. Matthew Robinson, McClean hospital

The recording of Robinson’s lecture was uploaded to McLean Hospital’s YouTube channel. It went viral, and it fueled outrage among the TikTok DID community. Some TikTok users went so far as to encourage people to “review-bomb” McLean Hospital. They did.

“Shame on you for your disgusting behavior towards DID Systems,” commented Sophie B. “Dr. Robinson should issue a public apology to each of the individuals featured in the video,” said Katherine Mogg. “Dr. Robinson accused multiple professionally diagnosed people with DID of faking their illness, took their videos without any prior contact or consent, and basically humiliated them for his own gain,” wrote Phoenix O.

“Absolutely disgusting that a hospital staffed by ‘medical professionals’ would endorse the humiliation of a formally diagnosed DID system to try to spread malicious, ignorant misinformation about how the disorder presents and manifests,” added Invikta. “Dr. Robinson will get videos without your permission and parade you around as if you’re a hypochondriac,” concluded another user.

One TikTok user, @thecabbagepack2.0, acknowledged that Robinson had some “valid concerns,” but said the way he “went about addressing them was not appropriate at all.” Robinson “addressed a concern of people harassing creators, and the proceeded to just use videos of creators with their usernames and people who are very popular within the DID community,” @thecabbagepack2.0 wrote on TikTok. “Like, that’s a doctor, and he can’t address his concerns without throwing people under the bus.”

Following the uproar, Robinson’s video was taken off the McLean YouTube channel, but it was reuploaded to the platform by other users. Robinson and the hospital declined to comment.

Dr. Kirk Honda hosts Psychology in Seattle, a YouTube channel and podcast. He explained on the platform that just because a video is “cringe” does not mean it’s fake. “On the other hand, some of the videos do seem fake to me, I can’t tell for sure,” he said. “Some of the people “faking” on TikTok might actually legitimately believe that they have it.”

Could people develop DID symptoms simply by being exposed to content on the platform? This is a serious concern that affects other mental or physical illnesses as well. Referrals for tic-like behaviors, for example, rose dramatically during the pandemic. TikTok videos with the hashtag #tourettesyndrome have gathered billions of views.

Dr. Alonso Zea Vera is a child neurologist at the Children’s National Hospital, based in Washington, D.C. He co-authored a 2022 study on “The Phenomenology of Tics and Tic-Like Behavior in TikTok.” It concluded that “current TikTok videos are poorly representative of [Tourette Syndrome] and could be misleading to the general public.” Other studies confirmed this.

Researchers found, for instance, that the vocal tic of the word “beans” spread like wildfire, including among non-English speakers. The only thing these patients had in common was being on TikTok.

“The portrayal of a lot of the neurologic symptoms that I’ve seen in TikTok seem either exaggerated or not consistent with the disease that they’re trying to portray,” said Zea Vera. He found that most patients referred for Tourette Syndrome do have “functional” neurologic disorders caused not by structural changes in the brain but changes in the workings of brain networks.

“It’s a real neurologic disorder. It’s caused by an alteration in the function of certain parts of the brain,” said Zea Vera. “But it’s not related to a structural lesion in the brain.”

Functional neurologic disorders mimic the symptoms of standard neurological disorders. Zea Vera notes that if a patient has a relative with epilepsy, they are more likely to present with seizure-like episodes. They are not faking the seizure; rather, their brain is tricking them into seizing. Zea Vera cautioned that functional disorders tend to worsen when people pay more attention to the symptom, which is why he urges some of his patients to stay off TikTok.

Social media-associated illnesses

Until 2021, pediatric psychiatrist Andrea Giedinghagen had not treated a single patient with dissociative identity disorder. At St. Louis Children’s Hospital, where she works, referrals started coming in around January 2021. “In September 2021 alone we saw as many as in the previous 6 months,” Giedinghagen wrote in a paper published in 2023 by Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. She attributes the surge to TikTok.

Giedinghagen suggested a new term to describe the TikTok presentation of DID: Social Media Associated Abnormal Illness Behavior (SMAAIB). It is a derivative of Mass Social-Media Induced Illness (MSMI) – when a patient involuntarily develops symptoms they have been exposed to on social media. MSMI spreads rapidly in cohesive groups, and even though social media users do not meet in real life, they share a strong sense of belonging and intimacy.

SMAAIB is an umbrella term that includes both the patient who unconsciously and involuntarily developed DID-like symptoms, and “the TikToker finally getting the attention he craves,” wrote Giedinghagen.

While some users may also be craving financial gain, TikTok is not a lucrative business for most influencers unless they have an enormous number of followers. Havapsy has 27,100 followers and allegedly made 1,350 euros since the creation of their channel. The Hive system has 19,900 thousand followers and disclosed an income of about £150 in the last year.

The public’s fascination with DID didn’t begin with TikTok, Giedinghagen notes, but it did amplify what she calls a sociocognitive model of illness – a set of behaviors perpetuated by societal expectations, exposure to media, or interaction with peers and therapists.

“Health emerges when adolescents are supported for who they are as whole human beings, not diagnoses. It’s not my job to sort of sit on a throne and bestow diagnoses from on high; it should be a collaborative process.”

Pediatric psychiatrist Andrea Giedinghagen

The path to healing from media-driven illness, she said, “comes first by disconnection, then connecting anew.” She recommends taking time off social media to disconnect from the feeling of belonging attached to a diagnosis.

“Health emerges when adolescents are supported for who they are as whole human beings, not diagnoses,” she said. “It’s also not my job to sort of sit on a throne and bestow diagnoses from on high; it should be a collaborative process.” ”

Some patients who self-diagnose with DID actually have borderline personality disorder or PTSD, Giedinghagen said, while for others, dissociating a bit is nothing to worry much about. “Sometimes I diagnose people with being human.”

People who go on TikTok to self-diagnose with DID, whether they have it or not, are by definition not doing well, Giedinghagen said, and most they often report a history of trauma, abuse and neglect. She encourages them to seek professional help. “Although TikTok can be a good source of community, it is not a great source of reliable mental health information,” she said.

Dissociative identity disorder is one of the most difficult mental illnesses to diagnose, and it can take years for a trained psychiatrist to do so. The average length of a TikTok video is 35 to 55 seconds. “There’s a lot of misleading information. There’s a lot of good information,” said Zea Vera. “But the fact that it’s so unregulated makes it hard to differentiate for someone without training whether this is true versus this is maybe misleading.”

Instead of “vilifying TikTok, we emphasize its potential as a platform to combat misinformation… particularly among younger generations.”

Journal of affective disorders

In January, the Journal of Affective Disorders Reports reported on the high prevalence of dissociative identity disorder content on YouTube and TikTok, but noted a stark difference between the two: Half the videos about DID on YouTube were useful, but only 5% of the TikTok posts on the condition were to be trusted.

“There has been a growing trend of adolescents presenting en masse with illnesses, such as DID, which can be attributed from viewing illness-related content by social media influencers,” the authors wrote. “The growing popularity of DID in media and social networks could be explained by individuals who try to make meaning of their emotional conflicts, attachment problems, and difficulties in establishing satisfactory relationships, as they may find the DID concept attractive… Individuals could find a sense of community online of people with a shared experience.”

The scientists recommended that healthcare professionals publish more educational content on social media and “learn to create more engaging content” for TikTok.

Instead of “vilifying TikTok,” they wrote, “we emphasize its potential as a platform to combat misinformation… particularly among younger generations.”

See Astrid Landon’s related story on the cultural history of DID:

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.