Did the Stanford Prison Experiment, One of Psychology’s Most Famous Studies, Really Turn People Into Monsters?

A riveting new docuseries talks with the former youths from a famous Stanford experiment that quickly devolved into violence and chaos.

A new documentary series on the study challenges us to reimagine what we’ve learned

The summer before his freshmen year of college, in 1971, Clay Ramsay lived with a few buddies just a few steps from Stanford University. They’d move between anti-Vietnam War demonstrations and a nearby coffee house, where they’d gather and play chess.

In those days, cafe bulletin boards often contained flyers recruiting students to take part in research studies and clinical trials. But the one that caught his eye he spotted in a local newspaper. He replied and ended up taking part in what would become one of the most famous psychology studies in history: the Stanford Prison Experiment. Its putative aim: to see what happens when you put good people in a bad situation.

The experiment proceeded in “a Gonzo fashion,” Ramsay told MindSite News. “There were not a lot of guardrails. This was the San Francisco Bay Area in 1971. It wasn’t the only weird thing that happened that year.”

The study offered recruits $15 a day, plus lodging, to participate. It was led by Phillip Zimbardo, a hip, goateed psychology professor who’d been hired at Stanford three years earlier. Students dubbed him the “disco psychologist,” giving the experiment an extra layer of appeal.

Most of the young men participated for the money, figuring they could use the “prison” time to read and study. About 100 candidates who responded were given personality tests and asked a set of questions, including whether they’d ever been in jail. They also signed contracts saying they couldn’t leave without good cause.

Zimbardo’s team would narrow the pool down to two dozen participants, which they divided via coin flip into two groups – prisoners and guards – to see how people would behave when placed into these roles with limited instructions like: no physical abuse, maintain law and order, and if the prisoners escape, the experiment is over.

“I didn’t give a shit. All I cared about was a summer job,” said study participant Doug Korpi in the documentary. “I thought ‘Oh my god this is a great thing. It’s a prison. It’s an experiment. I’ll have all this time in a cell. I’ll bring my books. I’ll study.’ I thought it was the perfect job.”

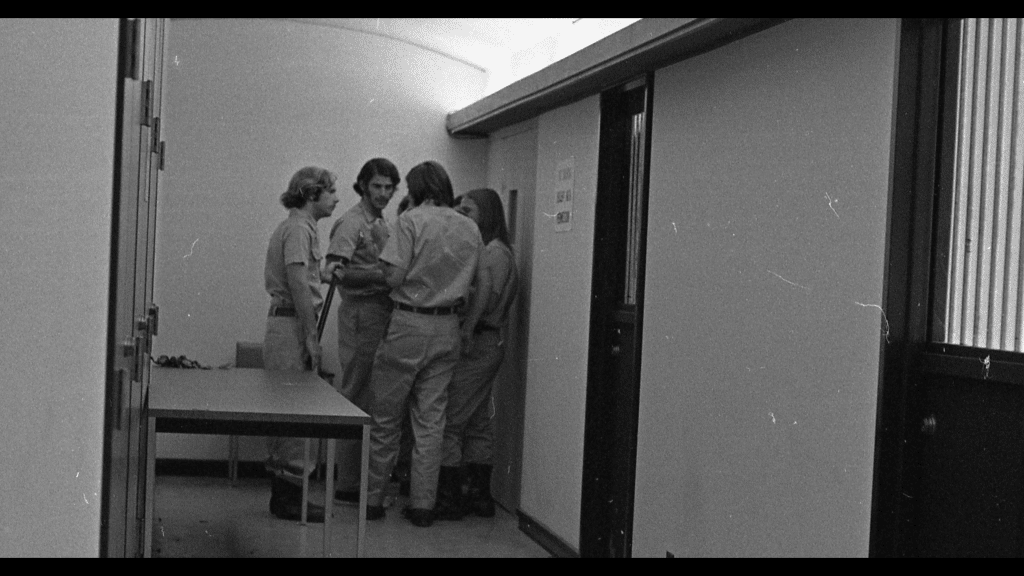

As part of the experiment, Zimbardo arranged for the “prisoners” to be arrested and brought by police to the makeshift prison on Stanford’s campus. From there, the experiment quickly devolved into chaos as the “guards” treated the “prisoners” with increasing violence and brutality, leading Zimbardo to terminate the two-week study after just six days.

The self-professed ringleader of the guards was Dave Eshleman, a theater student who’d spent his freshmen year being hazed at a fraternity and would use some of those tactics to embarrass and break down prisoners. His cruelty would earn him the nickname “John Wayne” after the film star who was loathed by students at the time for his support of the Vietnam War.

“I blame Zimbardo for doing that experiment on me. It was a horrible job and Zimbardo was the perpetrator. I was a victim.

Doug Korpi, a “prisoner” in the experiment

By day two, Korpi, who was selected to be a prisoner, realized no one would be bringing him his study materials and that he would be forced to engage with the guard’s cruelty, which included serving the prisoners food without utensils. From there, he would stage a “rebellion” with the other prisoners.

When the guards eventually took their clothing and beds as punishment, Korpi wanted out. He faked a stomachache, but was rebuffed by Zimbardo, who told him history was being made and he was the leader of the rebellion. Fearing he would not be able to leave the experiment, Korpi refused to participate and was thrown into “the hole,” a janitor’s closet meant to simulate solitary confinement. There, he would throw a tantrum until he was released from the study for having a nervous breakdown.

“I blame Zimbardo for doing that experiment on me,” Korpi says in the documentary. “It was a horrible job and Zimbardo was the perpetrator. I was a victim.” He also claimed his tantrum in the closet was an act. “The problem is he doesn’t care who he hurts along the way.”

The Replacement

On Day 3, Ramsay, a merchant marine, came to the campus basement where the “prison” had been set up to replace Korpi, and his arrival ignited the swift downward spiral of the experiment. He refused to go along with the guards’ antics and began a hunger strike that led to him also being placed in the hole.

Christina Maslach, a psychology professor who was in a romantic relationship with Zimbardo at the time and later married him, stumbled across the “prison.” She saw students dressed as guards and the student-prisoners clothed in shapeless sacks, chained together with paper bags over their heads.

“I was sick to my stomach,” she later told a group of psychologists in Canada. After she and Zimbardo left the site, she remembers screaming at him. “It is terrible what you are doing to those boys,” she yelled, recalling that “we had a fight like you wouldn’t believe.” That night Zimbardo decided to terminate the experiment.

Despite its shortened length, the experiment quickly became famous, turning Zimbardo into a scientific rock-star and media celebrity for decades to follow. It would be years before the ethics of the study were called into question.

“I was sick to my stomach. I told him,“It is terrible what you are doing to those boys. We had a fight like you wouldn’t believe.”

Psychologist Christina Maslach

The study took place just weeks before the riots at Attica Prison – where incarcerated men revolted at the barbaric treatment directed against them, proclaiming: “We are men! We are not beasts and we do not intend to be beaten or driven as such.” They seized guards as hostages and took control of the prison for four days – until Gov. Nelson Rockefeller ordered an assault by State Police, which killed 43 people – 33 prisoners and 10 guards.

Suddenly, reporters became interested in what had happened at Stanford – and the fact that Zimbardo had collected six hours of film footage added to the allure. Stories appeared on San Francisco television news, in the New York Times and in numerous other outlets. The footage – and the narrative offered by Zimbardo – suggested that anyone placed into a prison context can become cruel and abusive. Zimbardo’s writeups of his study would appear in scores of textbooks.

He went on to create a public television psychology course and defended Staff Sergeant Ivan “Chip” Frederick, a prison guard at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq accused of abuse and torture of prisoners. He drew on these experiences to write The Lucifer Effect: How Good People Turn Evil, a New York Times bestseller that explained “how situational forces and group dynamics can work in concert to make monsters out of decent men and women.”

But that version of reality came under attack in 2019, with the publication in the journal of the American Psychological Association of a paper by a French scholar, Thibault Le Texier. Titled “Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment,” it drew on interviews with 15 of the 24 subjects in the original experiment. Its findings formed much of the basis of a new documentary released last week by National Geographic.

The three-part series, The Stanford Prison Experiment: Unlocking the Truth, highlights issues with the original study, interrogates the science behind it, and explores the man made famous by it. It uses archival research and new interviews with participants including Eshleman, the theater student who admits to basing his sadistic guard roleplay on movies; a guard who refused to take part in the cruelty; Korpi, who admits to faking his nervous breakdown; and Zimbardo himself, in one of his last interviews before his death last month at the age of 91.

MindSite News spoke with Ramsey and the documentary’s director, Juliette Eisner, about the study and how the docuseries came together. This conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Josh McGhee: Why did you get started with this project?

Juliette Eisner: When I first started researching the Stanford Prison Experiment I quickly realized that few of the participants had ever really spoken about their experience in detail. It was always Dr. Zimbardo front and center, explaining the study and telling the story of what took place. I was interested in hearing about the experience from their perspective. Maybe the guards would want to apologize for or defend their behavior. Maybe the prisoners would want to air grievances. Little did I know at the time, but their stories would end up being quite different from Zimbardo’s narrative.

What did you think of the character that Dave Eshelman portrayed in the experiment?

Clay Ramsay: Well, you said it really well. He’s a character that Dave portrayed. And that’s the way I know Dave perceives it. All of the guards, I learned much later, had an orientation meeting in which they were told how to act and what to do. This was not an experiment in the sense of seeing how they would adjust. They were trained to proceed with a certain kind of style. And Dave had had acting training so he took it literally. He worked with what he had, which was Paul Newman movies, and he just went to town.

Considering the deluge of misinformation and disinformation in the media at the moment, how important is it for this documentary to come out and correct the record?

Ramsay: Well, it’s very important to me. I think Juliette Eisner did a superb job with really difficult material. Everyone who participated at her request winds up getting their say, and that includes Dr. Zimbardo. This is his swan song and he gives yet another account. When I watched it, I went ‘Oh, I had never heard him say this stuff before.’ And in fact, each decade, he varied the story a little bit, depending on what would sell under the new circumstances.

From the standpoint of avoiding bad science and understanding what parts are missing that make it bad science, this is just enormously valuable.

This series started as a movie — why was the format changed to a three-part series?

Eisner: There were so many twists and turns in this story and it became clear that a series would pack a bigger punch than a feature. We could play with our reveals and cliffhangers, and leave the audience wanting more. The structure of the series – which editors Mohamed El Manasterly and Steph Kelly had a huge role in shaping – was incredibly effective, in my opinion. We present the audience with a story they think they know in the first episode, we unravel that story in the second, and then we allow for Zimbardo’s defense, and a present-day reckoning in the third.

You were able to speak with Zimbardo before his death. What do you believe his motivations were? Do you think they changed over time?

Eisner: I feel very lucky to have had the opportunity to sit down with Dr. Z. We talked over the course of two days – I think we filmed six hours with him – and he was compelling, thoughtful, and patient. I can’t speak to what his motivations were, but I personally think Zimbardo believed he was advancing the understanding of human nature through the Stanford Prison Experiment, for the greater good. He was not shy about promoting his work and said that he wanted to spread psychology to the world. It gets tricky when you realize that certain details are left out of his telling of the experiment.

In the past, he has been far more narrow in his explanations of the study, and yet in our interview he was willing to muse on the importance of perspective. In the last episode he says that “reality and illusion are jumbled,” and that the study was like a play, where it was “up to the audience to pull it apart.”

Why did you feel it was necessary to bring everyone together? What was it like watching them reconnect?

Eisner: I had no idea how the reunion would unfold but my hope was that it would allow the participants to revisit their memories and experiences in the physical world (it’s not every day you get to recreate the Stanford Prison Experiment hallway!), reconcile with the other characters, better understand each others’ perspectives, and even find closure. I remember looking around the set during a heated conversation between the participants, and the entire crew and cast were laser-focused on what was taking place, eating up every last word.

There is this moment during the reunion, where people reminisce about you being put in ‘the hole.’ Why was that moment so emotional?

Ramsay: At the time, I was on a hunger strike, and so the guards didn’t have a lot of options. But they did have solitary confinement, which was a janitor’s closet that had been emptied out, so I went into the closet. There was a lot of sleep deprivation in the experiment, which is now officially defined as a torture technique. So when they shut the door, I went ‘Oh I can fall asleep here.’ This was a sense of relaxation. This was in no way like being put in actual solitary confinement in actual prison. There’s no comparison. But the others didn’t know whether this was negative for me or not. The guards were doing all kinds of things, like making the other prisoners come up one by one and bang on the door. It had no effect on me. I knew this was theater.

I could hear part of what was going on on the other side of the wall, where the experimenters were, and I couldn’t hear what they were saying, but I could distinguish the emotional tone. There were arguments breaking out. There was anxiety and stress. That worked for me. I was very happy to hear that.

In December of last year, I met some of these people again on the set. There was one person in particular who had said he had felt terrible for decades about having gone up and banged on the door instead of refusing to do it. He thought he was doing me some harm. And I was really surprised because it had not been my experience. I’m really happy that I was able to get across to him that he didn’t hurt me by doing that.

What do you hope people take away from this series?

Eisner: A good storyteller wields a great amount of power no matter how much he or she leaves out of their story. It is of utmost importance to allow all characters involved in a given event or narrative to speak up. I hope to inspire the audience to decide for themselves what is true, what isn’t, and to use whatever lessons remain to advance the original idea for good.

The Stanford Prison Experiment: Unlocking the Truth premiered November 13th. You can watch the series on the National Geographic channel or stream it via Disney+ or Hulu.

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.