A New Documentary Explores the Truth Behind the Infamous Stanford Prison Experiment

We interview the new film’s director and one of its participants. We also have a reported essay on what it’s like for people with Attention Deficit Disorder in real prisons.

Friday, November 22, 2024

By Josh McGhee

Happy Friday MindSiters,

We’re coming to you a week early to give you extra time to brine your turkey.

This month, we’re looking at a new National Geographic documentary questioning the findings of the Stanford Prison Experiment 50 years after the controversial study.

We’ll also take a look at what it’s like for people with Attention Deficit Disorder in prisons – what is and isn’t done to improve life inside for them. Finally, we’ll look at a new study about the treatment of Black children in a mental health crisis by police in California’s Alameda County.

Let’s get into it…

A fresh look at the Stanford Prison Experiment

The famed Stanford University psychologist Philip Zimbardo passed away last month more than fifty years after his controversial Stanford Prison Experiment.

While he would go on to write hundreds of articles, cover a range of topics for trade books, and develop a public television series about psychology, the 1971 study putting college students into a simulated prison system seems to be his enduring legacy.

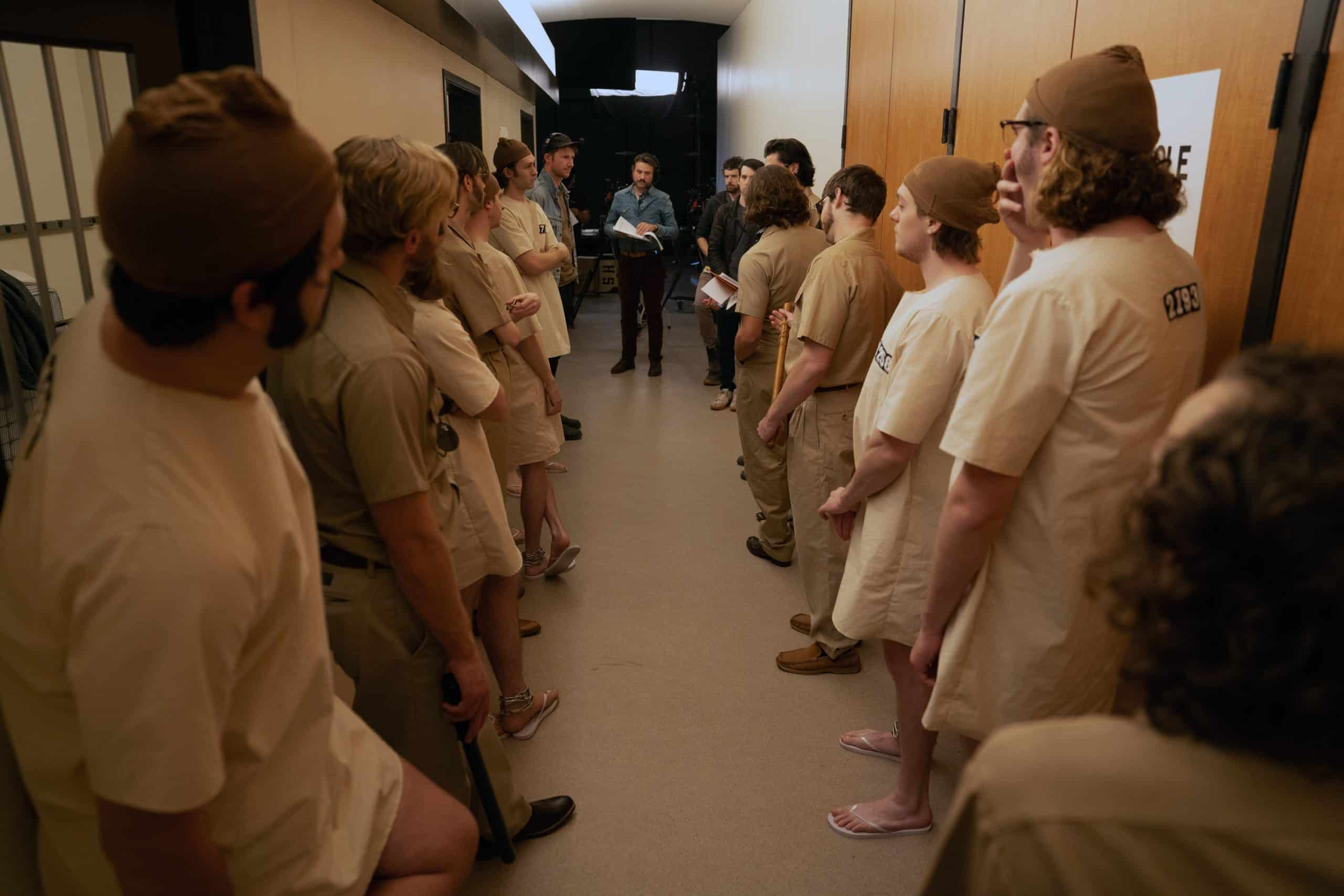

But, was the study a realistic simulation or a theatrical performance? A new three-part documentary series from National Geographic revisits the study, its participants and the story told by Zimbardo after it ended, laying out missing evidence and allowing viewers to come to their own conclusions about the study’s authenticity.

“It was always Dr. Zimbardo front and center, explaining the study and telling the story of what took place. I decided to find the subjects of the experiment because I was interested in hearing about the experience from their perspectives,” director Juliette Eisner told us in an interview-by-email. “Maybe the guards would want to apologize for or defend their behavior, maybe the prisoners would want to air grievances.”

Over the decades, experts have questioned the validity of the study, as well as raising ethical concerns about the treatment of the participants. But the critiques were largely confined to scholarly journals, with public perceptions more influenced by media portrayals like the 2015 indie film, the Stanford Prison Experiment. To his credit, Zimbardo didn’t shy away from the criticism and sat for an interview with Eisner’s team last year in what amounted to his swan song.

MindSite News spoke with Eisner and Clay Ramsay, who was enrolled as a prisoner in the experiment, about the series and the legacy of the Stanford Prison Experiment. Read our full story here.

ADHD in prison: A case for treatment

Kurt Myers was always a class clown. As early as elementary school, he was the performer mastering the art of distracting other students.

“My grades suffered for it,” Myers told Kevin Light-Roth, a journalist and organizer incarcerated in Washington state. “I was a bright kid, I just didn’t have the control or the attention span.”

Before his 10th birthday, Myers was diagnosed with ADHD and prescribed Ritalin, which he quit taking because of the side effects. His junior high school placed him in a special ADHD class. By high school, he was in and out of juvie, and at 16, he dropped out. Days after turning 17, he was charged with manslaughter after playing with a gun while drinking and accidentally shooting and killing his friend.

While ADHD alone didn’t send Myers to prison, his unchecked symptoms made it more difficult for him to course-correct. People with ADHD give up on school at a much higher rate and are more likely to fall into addiction and poverty. They end up in jail at nearly three times the rate of those without ADHD.

Robert Eme, a clinical psychologist who served on the Attention Deficit Disorder Association Work Group on ADHD and Correctional Health, told Light-Roth for his story: “There is no doubt that ADHD increases risk for criminal behavior, which explains why individuals with ADHD are overrepresented not only in American prisons, but in prisons in other countries.”

ADHD saturates the American prison system. While only 4.4% percent of the general public has ADHD, as many as half of adult prisoners and two-thirds of children in juvenile facilities have the condition. Yet no state in the country prioritizes ADHD treatment in its prisons.

Click here to read Light-Roth’s story about the challenges and needs faced by incarcerated people with ADHD, written for the Appeal and MindSite News.

Police more likely to handcuff Black children in mental health crisis

Police in California’s Alameda County are more likely to handcuff Black children — especially Black girls — than children of any other races when they’re experiencing mental health crises, according to a new study from Dr. Kenshata Watkins, a pediatric emergency physician at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in Oakland.

The study, published last week in the journal JAMA Network Open, looked at over 10,400 youth behavioral health emergencies handled by the county’s Emergency Medical Services Agency between 2012 and mid-2019. Police were 1.8 times more likely to handcuff Black children than their white counterparts — a disparity that climbed to being 2.6 times more likely for Black girls, according to the study.

Many of the interactions occurred after a parent called 911 because their child was experiencing severe emotional distress. Police often arrive before an ambulance and when “they get there, they do what police do,” Watkins said. “Police aren’t really trained to handle these types of emergencies, right?”

Nikki Jones, a sociologist-criminologist and professor of African American studies at UC Berkeley has spent a decade studying policing and violence in urban neighborhoods. “If anyone else were doing it, it would be a form of child abuse,” she told KQED. “But because the police are doing it and because they have this logic that’s based on their expertise, then we are supposed to read it as something other than extremely damaging to a child.”

For a study on race and law enforcement attitudes published last year, Jones rode along with police and observed that officers often view children of color as older and less vulnerable than they are. They also tend to focus on children’s obedience – which can be difficult for a child struggling with mental health challenges.

Read or listen to the full story here.

Until next month,

Josh McGhee

If you or someone you know is in crisis or experiencing suicidal thoughts, call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline and connect in English or Spanish. If you’re a veteran press 1. If you’re deaf or hard of hearing dial 711, then 988. Services are free and available 24/7.

Recent MindSite News Stories

Thousands of People in Prison Have ADHD. Why Aren’t They Receiving Treatment?

As many as half of all prisoners have ADHD, but they rarely get treatment, even though research suggests treatment can help reduce recidivism and ease reentry. Continue reading…

‘People Forget About the Fathers’

Losing a child is one of the most painful events a parent can endure, but services often focus on mothers – and fathers tend to grieve in isolation. These men formed a DIY grief group for dads. Continue reading…

Two in Five High School Students Feel Hopeless. In Areas with Fewer Supports, It’s Even Tougher

Many high school students are working passionately to support each other’s mental health. They may need to work extra hard if they live in a community that offers fewer services.

If you’re not subscribed to MindSite News Daily, click here to sign up.

Support our mission to report on the workings and failings of the

mental health system in America and create a sense of national urgency to transform it.

For more frequent updates, follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram:

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.

Copyright © 2021 MindSite News, All rights reserved.

You are receiving this email because you signed up at our website. Thank you for reading MindSite News.

mindsitenews.org

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.