Happier Anniversary: What I Learned about Grief from the Suicides of My Parents

A doctor who lost both parents to suicide on how he has learned to cope with the anniversaries of their deaths.

A doctor who lost both parents to suicide on how he has learned to cope with the anniversaries of their deaths

For years, I had nightmares around the November anniversary of my father’s death. My wife would shake me awake and tell me I was screaming. These nightmares, and the accompanying shrieks, remained relatively unchanged until my mother died, about 6 years ago and almost 39 years to the day since my father died. I expected the dreams would get worse in subsequent Octobers and Novembers, but actually they became less frightening.

Many people struggle with grief on the anniversary of a loved one’s death. My memories are particularly complicated because both my parents died by suicide and, like me, they were both physicians. After the shock of discovering my Mom dead in her kitchen and seeing how that unexpectedly changed me, I’ve been medically, psychologically, and existentially fascinated by the prolonged grief disorder called “anniversary reactions” – although “anniversity” might be a better name. An “anniversity” is an anniversary of adversity, and the struggle to come to terms with it has long shadowed my life. But each year, the anniversary of my mother’s suicide seems more instrumental in my being able to confront the death of my father, and much else.

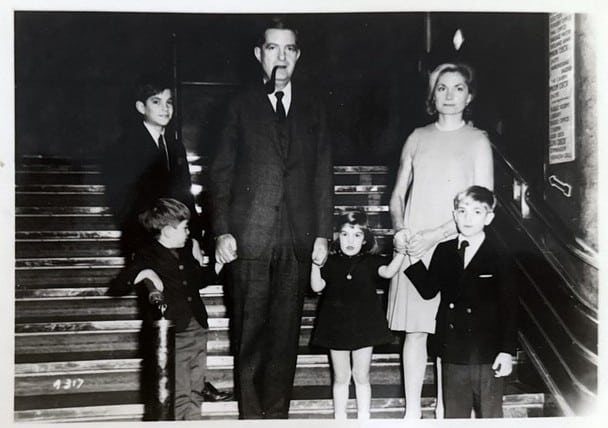

My father overdosed and killed himself when I was 20 and he was 57. Dad was about 6 feet tall, heavy, and very musical. He had brown eyes, salt and pepper hair, and a mischievous smile. He grew up in Dresden, Germany and left in 1938, just before the firebombing that became the setting of Kurt Vonnegut’s book “Slaughterhouse Five.” He eventually made it to the U.S., received his medical and psychoanalytic training, served in the army during World War II, and opened his practice as a psychiatrist/psychoanalyst in New York City. He married, had two sons (my half-brothers), divorced, and then married again (my Mom).

His death came without warning. I was a senior in college when Mom called saying she found him unconscious at his office desk. There was no mention of suicide. By the time I got home, he was already intubated in the hospital where he died the next day. At Mom’s request, none of the children went to see him. I was appropriately upset but stoic at his funeral. Feeling ungrounded, I took 3 weeks off to clean out his files and then returned to school without accepting his death. I experienced alternating periods of inertia and hyperarousal. I would disengage for a few days and then dive into things with inappropriate excess – whether it was working, acting out, drinking, or pretending that I was coping well. A college friend whose father had died “naturally” the year before tried to reach out to me. I pushed him away.

‘There’s something I want to tell you about’

A year later, while I was a first-year medical student in New York City, I met Mom for lunch. Sipping coffee, she shifted the conversation. “There is something I want to tell you about,” she said before describing Dad’s death. He was wearing a suit and tie and had carefully laid out files of papers, financial forms, doctors to refer his patients to, and other relevant documents. He had ample access to narcotics and used them to take his own life the way he wanted and when he wanted. I was angrier at my Mom for not telling me than I was at my Dad for killing himself.

My first clear anniversary reactions began almost exactly six years after Dad’s suicide. I dreamt of him standing in front of the house in New Hampshire where we vacationed each summer of my childhood. He was scruffy and unshaven and wearing blue jeans and an old blue shirt. He didn’t acknowledge me even though I was yelling at him repeatedly, “You can’t be here! You are dead!” I had similar dreams two or three times that week and almost every autumn for the next 33 years.

The script was always pretty much the same – though the scene varied between various familiar places such as our home. I would feel angry and disengaged for days to weeks afterward, and this process remained relatively static until my mother committed suicide in 2016. Her death helped me recognize that this was an anniversary reaction, which is a known grief disorder in the same psychiatric “family” as PTSD, was relatively common after the loss of a parent or child, and, most important, helped me deal with the deaths of both my parents.

My mother was a slender, gray-eyed, blond woman, 5 feet 4 inches at her peak but probably shrunken to 5 foot 2 over time. She grew up during the depression in a loving but misogynistic orthodox Jewish family in Flatbush, Brooklyn. After graduating from a local yeshiva and the High School of Music and Art, where she developed her talents as a painter, she went to Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania with no support from her parents and became a psychoanalyst. With even less parental support, she married my father. I never told my mother about the dreams I had every Fall or the associated anger and depression. If I had, she would probably have recognized them as a prolonged grief disorder – but I didn’t.

Director of grief

I learned about anniversary reactions after meeting M. Katherine Shear, a professor of psychiatry and founding director of the Center for Complicated Grief at Columbia. We met in a writing class about 10 years ago and I wondered what she did as the “Director of Grief.” I looked up some of her work, and I realized that I had been experiencing anniversary reactions for over three decades. My mood swings reflected the “disillusionment phase” after a disaster. It is supposed to be followed by a “recovery phase,” which was progressing very slowly for me, if at all, until my mother killed herself about two years after I met Shear.

Unlike Dad’s unexpected suicide, Mom had outlined her death to me, my two younger brothers, and a younger sister two years earlier at a restaurant on New York’s Upper West Side. She would dress nicely, take the pills she had sequestered somewhere in her apartment, and then get into bed where she would be elegantly found by one of her children within a few hours. I was the least supportive of her wishes. I told her that I did not believe anyone who was capable of thinking and imagining should take their own life except to save someone else. I tried numerous approaches – quoting Maimonides, asking her to paint more, exploring her memories. We all told her we loved her; reminded her of close friends who were still alive; and tried, unsuccessfully, to engage her with the internet. She was stubborn in her views, and at some point we all gave up or thought that she would never really do it. She used the next year or so to finish her last oil painting; a self-portrait with cameos of her four children and seven grandchildren, wilting flowers, a box of Cheerios, and the word “ephemera.” She said that the cereal box was her way of saying “cheerio” as a “goodbye.”

In mid-October of 2016, I found her lying on her tiled kitchen floor in a blue tee shirt and a pair of khaki shorts with a small pool of vomit next to her. The only sound was a maddening honking from a beige landline that dangled on its stretched, curly, cord. I mentally reached for the phone as “proof” that she really didn’t want to die and was trying to call for help. Instead of letting her go, I gave in to my doctor rescue fantasies and started CPR by the book.

I shook her, yelled at her “are you OK? are you OK?” (much as my wife my wife had yelled “Michael, Michael!” to wake me from my nightmares). As I rolled her onto her back and got down on my knees to start compressions, I looked hopelessly for any movements of her chest, put my ear next to her mouth, checked her pulse, and opened her eyes. There was no evidence of breathing, no pulse, and her pupils were dilated and staring at nothing. As I pushed, I noticed how delicate and fragile she was compared to the active sporty Mom I remembered.

I called 911 and continued a futile CPR as I shouted at the operator through a cell phone pinned between my chin and shoulder that my mother was dead. Less than 10 minutes later, two EMTs, a man and a woman, came through the door I had never locked with a gurney carrying a trash heap of equipment. They took over quickly and efficiently and continued what we all knew was a futile medical ritual. She was lying on the kitchen floor, being compressed by strangers, and then invaded by a tube shoved into her throat and a brutal electric shock.

As a son, I realized that I had been trying to save a life she didn’t want and had denied the death that she planned. Before calling 911, I should have tucked her in bed and cleaned up the kitchen. Now, all I could do was unsuccessfully ask them to stop their efforts and hasten their official acceptance of her death. Throughout this, my heart apologized profusely to her for the unnecessary indignities that I had facilitated. The apartment that once contained children, grandchildren, parents, and two doctor’s offices, was suddenly empty.

I tried to make amends by asking the EMTs if they would move her to her bedroom so my siblings wouldn’t see her in this undignified position. They were kind enough to do so, and I felt better even though I had not given her quite the grace she wanted. I washed the little bit of dried vomit off her face as she rested on pillows in her bed under a big yellow comforter and then called my wife and my brother David to tell them that Mom had died and would they please let the others know. I believed the EMTs would report that Mom had a heart attack in the kitchen and would never know she killed herself. Everyone else would believe that she had died quietly in her bed as she had planned. Then I undermined it all.

‘I love you all’

I saw a piece of her stationery lying upside down, almost invisible, against the white kitchen tabletop. It was a simple note in her very legible script that said, “Dear children, I love you all. I am sorry. Love Mom.” Without thinking, and ignoring admonitions from somewhere in my heart or brain, I showed it to one of the EMTs as if they were a medical colleague. Now instead of me calling the funeral home to pick up her body, the EMTs had to call the medical examiner and Mom would have to be invaded further during the autopsy “required” to confirm her cause of death.

Subsequently, my siblings arrived, and each sat with Mom where she lay pretty much as she had wanted. When the medical examiner arrived, she was initially annoyed that the body had been moved until I told her it was at my request and publicly thanked the EMTs for their kindness. She completed her exam in private and then took Mom away in a body bag hidden in a gurney so no one could see her – something she would have appreciated.

The medical examiner’s office was helpful and completed the autopsy quickly so we could bury quickly, according to Jewish practice. The report described her last meal (red wine and a beef dish with noodles), the narcotic found in her blood and intestines, and listed the cause of death as “suicide.” Though she had gone on dates, and even been involved in longer-term relationships, over the years, she had not, to my knowledge, removed her wedding ring and she had made it clear to my sister that she wanted to wear it even in death. She was buried with it on the ring finger of her left hand.

I dreaded the next autumn, expecting that the dreams and depression would get even worse. I was wrong, and my prolonged grief disorder actually began to move towards resolution after Mom died. The dreamscape in which I saw my father evolved. He was no longer out of place. Typically, the scene became him moving through a crowd at some major event or conference. He was always dressed in a nice suit, not too far from me, and negotiating passage through the dense gathering with a purpose, as if he belonged there and played an essential role. I would try to stop him and hug him – but he was always out of reach and would either keep moving or wave me off. I was disappointed, but no longer angry and I was more ready for the autumn blues.

I did not dream of Mom until about three years after she died. By then, I was waiting for her as a sign that she had moved on and was with Dad in death as she had wished in life. I welcomed her phantasmic arrival instead of running from it.

A door to our recollections

Later, I reached out to Shear to better understand anniversary reactions. She explained to me that most of us feel some recurrence of bereavement feelings when there is a reminiscent cue, whether a date or a photograph, and that “what we experience is the interaction of the environment inside (our memories) and the environment outside (our cues).” She suggested a metaphor of a “door” that impedes our access to an internalized room containing our recollections of a loved one. Some of those wistful, joyful, or infuriating echoes slip under the door or around the edges in response to small reminders causing momentary sadness, yearning, delight, remorse, or anger. During a major anniversary reaction, however, the door bursts open releasing an intense flood of thoughts and emotions. Sometimes a person can bear the flood, sometimes they will feel strong guilt, rage, anxiety, or despair as their grief is activated again, and sometimes this can be overwhelming.

I could put my father’s death in a compartment like a child’s old toy and ignore it because I never really experienced it. My mother’s death was right there, and I was an adult, and I had to deal with it in the present. The anniversaries of my parents’ death have fused into a single event, and I have flashbacks to that afternoon in the kitchen. I have come to realize that her suicide, and my reactions to it, are both intimately related to my father’s suicide 39 years earlier. It was his unexpected and solitary exit that provoked my mother to outline her own demise so openly, as if she were creating a work of art that would be fully unveiled at the time of her choosing.

Shear says that there is general agreement that we don’t actually complete grief. We continue to learn from our relationships with loved ones even after they die. For me, it took the shock of Mom’s suicide for me to recognize and accelerate the mourning process for both parents. Their deaths spared me the pain of watching them diminish with age but also denied me the feeling of remuneration for taking care of them as they once cared for me.

Shear suggested a number of approaches. The first was to “take time off each year to take care of yourself and honor the person who died.” Each year, I apologize to my Mom for interrupting her death and to my father for not supporting him more in life. Another was to “lean into it by normalizing it” which is what I have done for years and what I think prevented me from understanding what was happening. A third was “to deepen other relationships by sharing.” That is what I am doing now.

The apartment in which we all lived, and our parents died, is now occupied by another family. I have no desire to see their home. I still speak to my parents, sometimes verbally but more often internally, in an effort to complete the dialogue I wish we had had years ago. Every autumn, I feel closer to completing this task as I also create a more realistic, “less than perfect,” view of them. I accept my father’s substance abuse and anger and my mother’s stubbornness and refusal to progress into the 21st century as parts of their humanity.

Dad killed himself at a time when acknowledging substance abuse would have been considered a failure that was unacceptable to someone who had escaped the Holocaust and managed to thrive in a new country. In retrospect, Mom’s greatest fear was becoming a burden to her family and her few close friends who were still alive. She killed herself as our father did, only she shared her plans in advance because she didn’t want to burden us with any uncertainty or guilt that there was something we could have done to stop her.

I love them more for it. I am almost proud to say that in my autumn dreams of 2024 my father and I actually moved a pile of leaves off a beach together. This was the first time we really acknowledged each other in over 45 years. Maybe we’ll speak next fall and maybe, one year, Mom will be there too.

Michael Rosenbaum, MD, is a physician-scientist and professor emeritus of pediatrics and medicine at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City. He is also a practicing pediatrician and a member of the Columbia Narrative Medicine Journalism Workshop. His translational research focuses on understanding the regulation of body weight from the lowly adipocyte to the highest cortical centers of the brain and his op-ed and narrative medicine work has appeared in The NY Times, The Hill, Fortune, USA Today and elsewhere.

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.