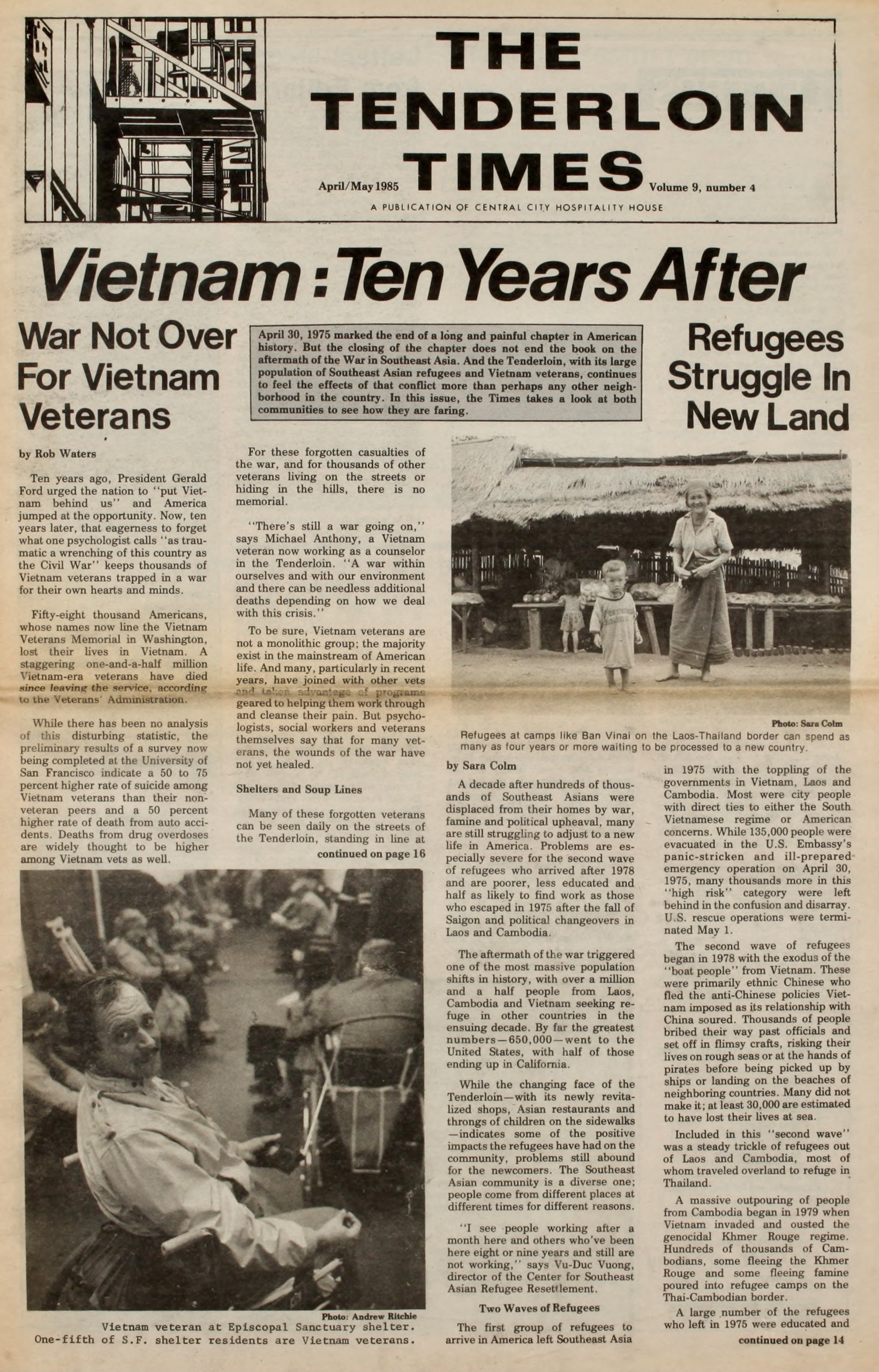

Refugees Struggle in New Land: A View from 40 Years Ago

In 1985, The Tenderloin Times explored the lives of Southeast Asian refugees and U.S. veterans 10 years after the end of the Vietnam War. This story offered a look at the efforts by three very different Southeast Asian refugee communities to rebuild and adjust to their new lives in a new country.

Editor’s note: Forty years ago, The Tenderloin Times, a community newspaper that served the inner-city Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco, published a package of stories linked to the 10th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. The Tenderloin then, as now, was home to thousands of refugees from Southeast Asia who had fled the war and political persecution, along with many American military veterans who had fought in that war, many of whom were shattered by the experience and had become homeless.

The stories were originally published in the April/May 1985 issue under the headline “Vietnam: Ten Years After.” Times co-editor Sara Colm wrote about the experiences of Southeast Asian refugees living in the Tenderloin and their journey to the U.S. Today we present those stories — as they were written 40 years ago. You can view an online archive of the Tenderloin Times here.

A decade after hundreds of thousands of Southeast Asians were displaced from their homes by war, famine and political upheaval, many are still struggling to adjust to a new life in America. Problems are especially severe for the second wave of refugees who arrived after 1978 and are poorer, less educated and half as likely to find work as those who escaped in 1975 after the fall of Saigon and political changeovers in Laos and Cambodia.

The aftermath of the war triggered one of the most massive population shifts in history, with over a million and a half people from Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam seeking refuge in other countries in the ensuing decade. By far the greatest numbers — 650,000 — went to the United States, with half of those ending up in California.

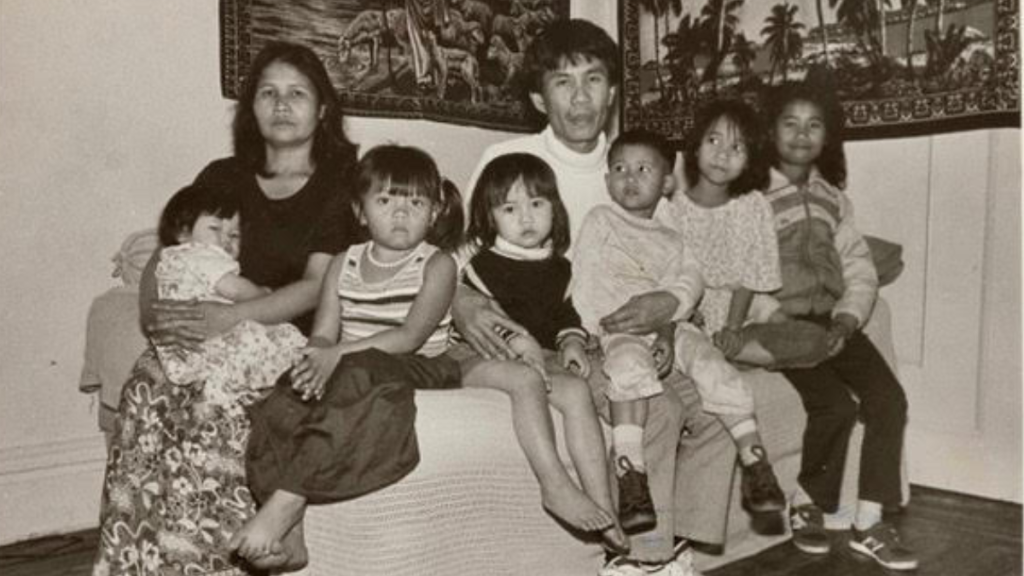

While the changing face of the Tenderloin — with its newly revitalized shops, Asian restaurants and throngs of children on the sidewalks — indicates some of the positive impacts the refugees have had on the community, problems still abound for the newcomers. The Southeast Asian community is a diverse one; people come from different places at different times for different reasons.

“I see people working after a month here and others who’ve been here eight or nine years and still are not working,” says Vu-Duc Vuong, director of the Center for Southeast Asian Refugee Resettlement.

Two Waves of Refugees

The first group of refugees to arrive in America left Southeast Asia in 1975 with the toppling of the governments in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Most were city people with direct ties to either the South Vietnamese regime or American concerns. While 135,000 people were evacuated in the U.S. Embassy’s panic-stricken and ill-prepared emergency operation on April 30, 1975, many thousands more in this “high risk” category were left behind in the confusion and disarray. U.S. rescue operations were terminated May 1.

The second wave of refugees began in 1978 with the exodus of the “boat people” from Vietnam. These were primarily ethnic Chinese who fled the anti-Chinese policies Vietnam imposed as its relationship with China soured. Thousands of people bribed their way past officials and set off in flimsy crafts, risking their lives on rough seas or at the hands of pirates before being picked up by ships or landing on the beaches of neighboring countries. Many did not make it; at least 30,000 are estimated to have lost their lives at sea.

Included in this “second wave” was a steady trickle of refugees out of Laos and Cambodia, most of whom traveled overland to refuge in Thailand.

A massive outpouring of people from Cambodia began in 1979 when Vietnam invaded and ousted the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime. Hundreds of thousands of Cambodians, some fleeing the Khmer Rouge and some fleeing famine poured into refugee camps on the Thai-Cambodian border.

A large number of the refugees who left in 1975 were educated and highly skilled, and have been able to find jobs. For some, it wasn’t an easy process — they arrived before the federal government provided any cash assistance to refugees — and they started first as dishwashers or busboys.

Today, single refugees are eligible to receive approximately $272 a month plus food stamps (roughly equivalent to General Assistance) during their first 18 months here. Families are eligible for AFDC.

“Many of the Vietnamese are doing fine now, although that doesn’t mean we don’t have problems still,” says Michael Huynh of the Refugee Resource Center. He points to the numerous Vietnamese-owned businesses in the Tenderloin as well as several Vietnamese-owned electronic firms in Silicon Valley as examples of success. “We were more exposed to the Western civilization than the Lao and Khmer. Whether we like it or not we know the system — Western culture — better than the others.”

Myth of the wealthy ethnic-Chinese Vietnamese

But the myth of the “wealthy ethnic-Chinese Vietnamese” has been discounted by a recent U.C. Berkeley study. Arriving in the second wave of refugees, the ethnic Chinese were primarily shopkeepers back home. In general they had far less education, are poorer and less likely to be working than their compatriots who, associated with the U.S. government or the former South Vietnamese administration, arrived here earlier.

In addition to the ethnic-Chinese shopkeepers, other recent arrivals include peasants, farmers, fishermen or nomadic tribespeople from Laos and Cambodia. This group had little contact with western lifestyle and fewer years of formal education: a fair number of them are illiterate in their own language.

Most of the Lao refugees — the lowland Lao and the Hmong and Mien hilltribes people — as well as the Khmer, were farmers back home. Coming from a rural village society to a dense urban environment like the Tenderloin is quite a shock, especially for the nomadic tribespeople from the hills of Laos.

“It’s totally helpless — totally blind — for them to live in a city,” says Buonchon Thepkaysone, the Laotian co-director of the Refugee Women’s Program. “But they have no choice.”

“They want to do the same job they did back home. They were farmers before. Now they are forced to train for jobs as janitors.”

—BUONCHAN THEPKAYSONE

Aside from difficulties getting used to Western culture, language is usually cited as the main problem for Southeast Asian refugees. A survey by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services of refugees entering the country between 1979 and 1981 showed that only 20 percent had at least “survival” level English skills, and only 10 percent were sufficiently proficient in English to look for work on their own during their first month in the U.S.

Without language, a job is almost impossible to find. But even for those with English skills, cultural differences can make landing a job difficult. Dean Leng of Khmer Samaky gives the example of a Khmer refugee doing poorly in a job interview. “Khmer are fairly passive and reserved. They are not like the Americans when faced with a lot of questions. They may feel apprehensive.” For example, job applicants may appear to lack confidence because they don’t look the interviewer in the eye, when that is simply a Khmer custom.

Once farmers, now forced to train for janitor jobs

There are various job training programs for refugees but for many it is difficult to match their skills — as ex-farmers — with the current job market. “Really they want to do the same job they did back home,” says Thepkaysone of the Lao and Khmer. “They were farmers before. Now they are forced to train for jobs as janitors.”

Sometimes the scars of a difficult past impede the effectiveness of a job training program. Heng Han, a Khmer who suffered repeated beatings at a forced work camp under the Khmer Rouge, says that it is difficult for him to remember things now from his janitorial training and he is very discouraged.

Language problems lead to other difficulties and cultural misunderstandings. A frequently cited problem for Tenderloin refugees is ignorance of tenants’ rights. Refugees don’t know what to do about common Tenderloin housing problems such as leaky ceilings or illegal rent increases, according to Tho Do of the Vietnamese Youth Development Center. “They don’t know their rights and feel they do not want to say anything to cause any problems,” she says. Many of the refugees live in extremely overcrowded and unhealthy accommodations in the Tenderloin, with a family of eight or nine cooped up in a studio apartment.

“Every Cambodian has at least one of their family members who was killed.”

—SILEN NHOK, CAMBODIAN RESETTLEMENT WORKER

A growing but almost invisible problem in the Southeast Asian community is emotional difficulties brought on by the lingering effects of living in a war-torn country, suffering a harrowing escape, seeing the death of friends and family and feeling the guilt of leaving others behind. Coping with a painful past exacerbates the seemingly more petty problems of trying to fit into a vastly different world. Added on to other everyday aspects of life in the Tenderloin — poverty, unemployment, overcrowding, welfare cuts — the stress can become unbearable.

Psychological Scars

Refugees suffer serious mental health problems two to six times more than their American neighbors, according to a Santa Clara County Mental Health study.

The Khmer (Cambodian) population, who suffered an especially brutal ordeal under the Khmer Rouge, are hardest hit. They are six times as likely as the general population to be seriously anxious, frightened or depressed, according to the study. “Every Cambodian has at least one of their family members who was killed,” says resettlement worker Silen Nhok.

Others suffer the guilt and frustration of leaving family members behind. Says an anguished Vinh Ngo, who was associated with the American Green Berets in Vietnam and whose family is still there: ‘When the Americans pulled out I was five years in prison. The reason I work so hard is to make enough money to get my child out of Vietnam.

The stress of getting used to a new country is played out in family dynamics. Separation or divorce is sometimes the result, an especially hard blow for Asians where family is all-important. Citing family violence — wife and child abuse — as a major problem for the Lao and Khmer communities, Thepkaysone explains, “After the family settles down the women start to accept the idea of equality between men and women. The men misunderstand and say the woman is forgetting the unique custom from the old country. The woman is trying to help out financially by getting a job outside but doesn’t have time for housework and cooking. Arguments and violence go on in the family leading to separations and divorce.”

The children suffer in this too, says Thepkaysone, because the parents have less time to spend with them because they are working. “When children pick up dirty words at school, parents spank them like back home and neighbors report to the police,” he says.

Scars of a painful past

Aside from the problems in their current family life, refugee children bear the scars of a painful past. “Kids from 3rd, 4th and 5th grades have memories of getting on boats, being pirated, boats sinking, family members drowning,” says Marian Wake, a counselor at Redding School. “There’s a lot of depression over that. One Cambodian child saw her father decapitated. They also suffer grief for the language problem.”

A growing gap between the younger and older generations leads to other problems. Refugee leaders cite the loss of respect for elders and parents as a major problem for Asian cultures where family is central.

Many of the older people are homesick, facing an alien world and advancing years with the sorrow and indignity of losing their former status and familiar life. More and more of the elders are facing the psychological problem of thinking of home, says Thepkaysone. “They’ve lost their role.”

“The children will play a very important role as they grow up. They will be a bridge between the young and old.“

—BUONCHON THEPKAYSONE

An example is a Lao refugee, 63 years old, who was the tribal leader of his village back home. He grew up hunting and farming, never wearing shoes, but respected by his people. Living now in the midst of urban San Francisco, he wears running shoes and spends much of his time at home. Unable to speak a word of English, he is barely able to ride the bus.

Increasingly the older refugees are suffering from depression, homesickness, even alcoholism, says Thepkaysone. “The children will play a very important role as they grow up,” she says. “They will be a bridge between the young and old.”

Healing the psychological wounds many refugees suffer is difficult in a new culture where old support systems, especially extended family, are gone. Traditional western mental health approaches don’t always help.

“In Asia people don’t talk about their personal problems,” says Bouakham Saycocie. Echoes Thepkaysone: “People don’t tend to open up to the mental health workers who don’t necessarily speak the same language or understand our culture.”

Success Stories

- A young Vietnamese girl whose parents are still in prison in Vietnam got into U.C. Berkeley after four years in America.

- The first Khmer restaurant in San Francisco opening on Larkin Street.

- The opening this month of the first refugee-owned community center in the country by the Center for Southeast Asian Refugee Resettlement.

“We’ve been struggling all our life,” explains Michael Huynh. “So once we’re in a peaceful country all our energy goes into getting ahead.”

Others, such as Buonchon Thepkaysone, point proudly to the emergence in the last several years of refugee leadership. “We’re forming community organizations of our own to continue the traditions from back home and to help families with cultural misunderstandings.”

The Southeast Asian refugees are a positive influence on the Tenderloin, the neighborhood that some 10,000 of them now call home. Pointing to the positive influence of Asian businesses, Vu-Duc Vuong says, “In the last year, we see the whole neighborhood awakening and trying to keep this as a viable neighborhood. We don’t want to let it go to seed again, becoming a hard core area, and we also don’t want to become just an extension of downtown. We want a place where people can live and keep their family lifestyle in the Tenderloin.”

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.