War Not Over For Vietnam Veterans: A View from 40 Years Ago

Forty years ago, The Tenderloin Times, a community newspaper in San Francisco, marked the 10th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War with a package of stories. The Tenderloin then, as now, was home to thousands of refugees from Southeast Asia, along with American military veterans who had fought in that war. This story looks at the experience of those veterans.

Editor’s note: Forty years ago, The Tenderloin Times, a community newspaper that served the inner-city Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco, published a package of stories linked to the 10th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. The Tenderloin then, as now, was home to thousands of refugees from Southeast Asia who had fled the war and political persecution, along with many American military veterans who had fought in that war, many of whom were shattered by the experience and had become homeless.

The stories were originally published in the April/May 1985 issue under the headline “Vietnam: Ten Years After.” Times co-editor Rob Waters, now founding editor of MindSite News, wrote about the American soldiers who had fought in Vietnam and how they were coping with the trauma they had experienced. Today we present those stories — as they were written 40 years ago. You can view an online archive of the Tenderloin Times here.

Ten years ago, President Gerald Ford urged the nation to “put Vietnam behind us” and America jumped at the opportunity. Now, ten years later, that eagerness to forget what one psychologist calls “as traumatic a wrenching of this country as the Civil War” keeps thousands of Vietnam veterans trapped in a war for their own hearts and minds.

Fifty-eight thousand Americans, whose names now line the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, lost their lives in Vietnam. A staggering one-and-a-half million Vietnam-era veterans have died since leaving the service, according to the Veterans Administration.

While there has been no analysis of this disturbing statistic, the preliminary results of a survey now being completed at the University of San Francisco indicate a 50 to 75 percent higher rate of suicide among Vietnam veterans than their nonveteran peers and a 50 percent higher rate of death from auto accidents. Deaths from drug overdoses are widely thought to be higher among Vietnam vets as well.

For these forgotten casualties of the war, and for thousands of other veterans living on the streets or hiding in the hills, there is no memorial.

“There’s still a war going on. A war within ourselves and with our environment and there can be needless additional deaths depending on how we deal with this crisis.”

—MICHAEL ANTHONY, VIETNAM VETERAN AND COUNSELOR

“There’s still a war going on,” says Michael Anthony, a Vietnam veteran now working as a counselor in the Tenderloin. “A war within ourselves and with our environment and there can be needless additional deaths depending on how we deal with this crisis.”

To be sure, Vietnam veterans are not a monolithic group; the majority exist in the mainstream of American life. And many, particularly in recent years, have joined with other vets and take advantage of programs geared to helping them work through and cleanse their pain. But psychologists, social workers and veterans themselves say that for many veterans, the wounds of the war have not yet healed.

Shelters and Soup Lines

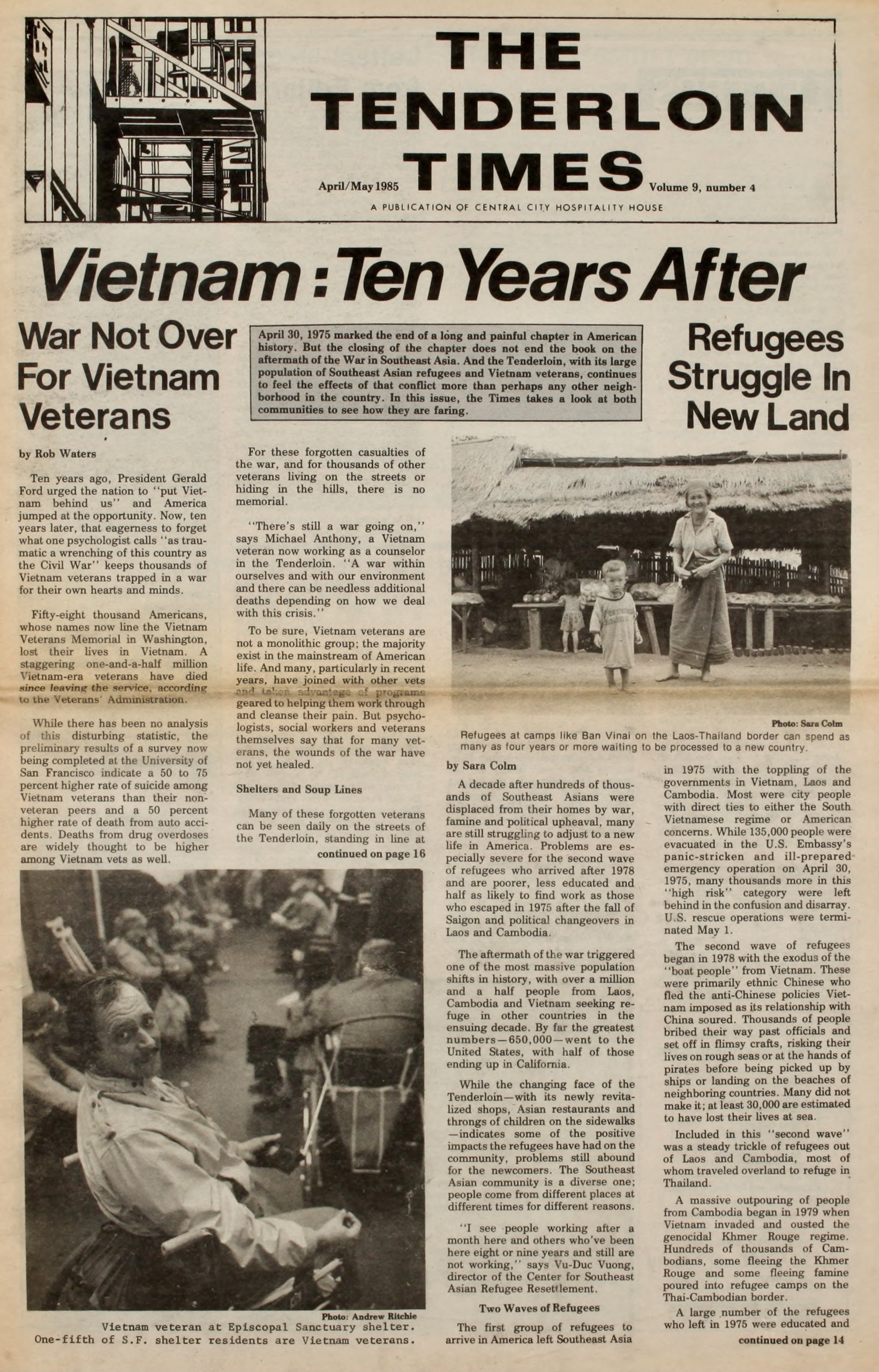

Many of these forgotten veterans can be seen daily on the streets of the Tenderloin, standing in line at soup kitchens and sleeping in shelters for the homeless. In a recent survey of San Francisco’s homeless shelters, nearly half of the residents were veterans and fully one-fifth were Vietnam-era veterans. By comparison, Vietnam-era vets make up less than one-twentieth of the overall population.

“A great number of Vietnam vets have become part of that lost generation that just wanders the streets and lives on the streets,” says Ron Perez, a prisoner services specialist in the San Francisco county jails who is himself a Vietnam veteran.

‘Over the course of the last 10 years, Vietnam veterans in general have definitely matured. Many are successful, many are married, many are getting politically active,” says Perez, “But a good number have been left behind and we’re seeing that in our jails and on our streets.”

According to Perez, 25 percent of the inmates in the San Francisco jail system are Vietnam vets. Most are there, he says, for offenses related to the use of alcohol or drugs. And of those, “80 percent at least did not have a substance abuse problem prior to the military,” he adds.

“Vietnam was America’s first teenage war. The average age of soldiers in World War I was 26, in Vietnam it was 19.”

—JACK MCCLOSKEY, LONGTIME VETERANS COUNSELOR AND ACTIVIST

To these problems plaguing Vietnam veterans, add high and prolonged unemployment, high rates of divorce and a general level of isolation and alienation from American society found among few other groups of Americans.

Beneath these problems lies a well of bitterness, frustration and rage that runs so deep as to be almost incomprehensible to a non-veteran. Bitterness at being forced as teenagers to endure the horrors of a senseless and unwinnable war, frustration at being lied to by the government and castigated by peers and rage at now feeling discarded like used cannon fodder with inadequate services, inadequate benefits and inadequate job opportunities. “Vietnam was America’s first teenage war,” points out Jack McCloskey, a long-time veterans counselor and activist. “The average age of soldiers in World War I was 26, in Vietnam it was 19.”

“You take a 19-year old who is not fully formed, expose him to heavy life-threat, deprive him of the ability to understand what happened, and what it leads to is a severe disruption of the development of that person,” says Dr. Stephen Pennington, a psychologist who works with veterans at a Veterans’ Administration clinic in Oakland.

Don Patterson, also known as “Highway Hobo” has spent the last five years on streets across the country and now lives in a special Tenderloin hotel program. He is still struggling with the memories and the aftermath of Vietnam. “The idea was we’re gonna go over there and fight communism, go over there and save those people and then you get over there and find they hate and attack Americans.”

Patterson recalls the insanity, the breakdowns in order, the tremendous fear of the unknown. “You’re over there, you had to adjust — who’s the enemy? Old men, women and children are taking out more Americans than we want to admit. Americans are killing Americans. Everything was starting to screw up. So how do you maintain order, how do you keep atrocities from happening?”

The Real World

While in Vietnam, soldiers dreamt about what they called “the real world”, a return to normalcy after getting out of the Vietnam nightmare. But the nightmare was not so easily left behind. And things back home were not so normal. For many, if not most veterans, the transition back was a jarring one.

“When we came back, there was absolutely no support, no debriefing sessions, no nothing,” says Kevin Gagen, a Vietnam vet and Tenderloin social worker. “It takes a bit of imagination to understand that on Thursday, you could have been in a firefight, watching a village burn or watching your buddies die and on Saturday you could be on Market Street in San Francisco. But how do you just forget what happened yesterday?”

One typical method was that of a veteran who hid away for eight months. “I just kept the heat at 90, kept a blanket around me and drank wine. The only time I went out was to buy a bottle. In Vietnam, you always talk about the real world, but I wasn’t ready for it when I got there.”

American soldiers came back to society that was being ripped apart by the war and that offered little support or understanding to the returning veterans. To their peers, they were baby-killers and war criminals; to their elders, they were drug addicts and the first Americans to lose a war.

Don Patterson flew in on his return to the Oakland Army base and was spit at on his first day back. Two days later, he went to a demonstration in San Francisco. “People were sitting there talking about American pilots who were that down and they were clapping. They were cheering about American pilots shot down. I felt like I wasn’t accepted by America and I didn’t want to accept America, I didn’t want to be part of cheering other American deaths.”

James Thygesen, who was also spit at on his return, went with his father to a VFW bar a couple of weeks after his return and was asked by a patron where he had served. “I told him Vietnam and he laughed. He said, ‘That wasn’t no war.’”

After getting out of the service, Thygesen said, “I didn’t care about anything. I didn’t want to have any close friendships. I just wanted to detach myself from people. I didn’t want anyone to get too close.”

If returning veterans wanted to bury their experiences, they came back to a country that was only too happy to oblige. “Society at large did not help them do the natural thing — digest, process and overcome their experiences,” says Pennington. “So veterans were basically deprived of what, under natural circumstances, would have helped heal the wounds of war. Their folks would support them being over there but didn’t want to talk about it when they got back”

“Things broke down between me and my Dad,” recalls Don Patterson. “We didn’t adjust (to each other) at all. He thought, “The kid’s gotta be off, crazy. But he’s coming from World War II.”

“A lot of us learned to love over there. You share food, bullets, the shirt off your back, your dreams, your lives, everything. You become tight — ‘asshole tight’, we called it.”

—MELVYN ESCUETA, COUNSELOR WHO WORKS WITH TENDERLOIN VETERANS

Upon returning, vets also found that they had lost one of the things that had sustained them while they were in Vietnam — the close friendships they developed with their fellow soldiers.

“A lot of us learned to love over there,” said Melvyn Escueta, a counselor who works with Tenderloin veterans. “You spend a year over there, share food, bullets, the shirt off your back, your dreams, your lives, everything. You become tight — ‘asshole tight’, we called it.”

But in the “real world” of America, men don’t have relationships of that depth with other men. And given society’s repugnance with the war, relationships with women were hard to start and even harder to maintain. The result has been a very high divorce rate among Vietnam veterans.

“I think a lot of Vietnam vets just didn’t know how to be intimate with women,” says Escueta. “They did on the surface what they were supposed to do (as husbands) but they never gave to their wives the kind of love they gave to men in Vietnam.”

Many veterans also became afraid of love. Escueta believes, because they had seen too many people they did love get killed. “If you learn to love for the first time in the purest sense and the person gets killed, you start feeling that if I do love, the person will die. But by bit, you become more alienated; it’s another reason to just stay by yourself.”

No Jobs For Helicopter Gunners

Coming back, veterans found their job skills unsuited for the employment world; “The market for helicopter gunners was not real high,” observed Jack McCloskey. Those who did find jobs often found themselves unwilling to relate to the structure and authoritarian nature of most workplaces. Many vets have gone through dozens of jobs since they left the service.

Turning to the Veterans Administration for services has also been a disappointment and further stress on many vets, who find the “Big Green Machine,” as they call it, uncaring, unresponsive and bureaucratic.

“The V.A. is basically extremely suspicious of Vietnam veterans and has the attitude that vets who apply for benefits are trying to manipulate to get something they don’t deserve,” said Mike Blecker of Swords to Plowshares, an independent advocacy and service organization that assists veterans in dealing with the V.A. “Their operating policy is to try to deny whenever possible.” (Editor’s note: This MindSite News story looks at a support program for veterans run by Swords to Plowshares, which still operates today.)

In the final years of the war, some veterans, most notably Jack McCloskey, began to push the V.A. to set up special programs for returning veterans, who, they argued, had special problems and needs. The V.A. resisted strenuously and it was not until 1981 that Operation Outreach was funded by Congress and launched.

This program consists of drop-in centers throughout the country where Vietnam-era veterans can go to get counseling, referral and general support services.

These vet centers, as they are known, are the most striking example of one of the major strengths of the Vietnam veterans community — the commitment of so many vets to helping others. Vietnam veterans can be found in agencies throughout San Francisco, working with fellow veterans — and fellow citizens — who are in need.

Vets Helping Vets

It is a phenomena that is readily noticeable and it is also a source of great pride for many veteran activists and social workers.

“Since I left Vietnam, I always felt that my mission was not accomplished,” says employment counselor Charles Gallman. “I always felt that working with other vets was my way of accomplishing the mission.”

Perhaps because of this commitment on the part of many veterans — and because society has made some steps towards welcoming and thanking Vietnam veterans — more vets are coming forward for help now than in the past.

“It’s one thousand times better now than it was 13 years ago,” says Steve Pennington. “Vets don’t have to hide their identity as Vietnam vets and society has made some steps towards dealing with its own Vietnam trauma.”

For Jack McCloskey, us for many other Vietnam vets, the opening of “The Wall,” the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, was at least a partial acknowledgement by America of the debt it owed the veterans and was one step in the healing process. It was also an emotional experience.

“I ran into one guy I had treated as a medic, I had sewed him up in ‘68, his head was split open,” McCloskey recounted. “He has survived. I had never seen him since and he recognized me. We just started crying together and talked about some of the guys who didn’t make it.”

“Seeing all those names on the wall was very heavy emotionally but it brought one thing up — the sense of loss for nothing. It also reaffirmed that we have to do everything in our power to see it never happens again.”

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.