Are Chatbots Safe – and Are They Effective? The Former Head of the NIMH Weighs the Evidence

Instead of a mental health solution, catbots. may be something else entirely: the front door to the mental health system.

This column originally appeared on Thomas Insel’s Substack column, under the title Chatbot Safety: Red Teaming, Jail Breaking, and Real World Use. We are republishing it as part of AI and Our Mental Health, a new, ongoing series of interviews and essays.

This may be the year when more people turn to chatbots than to human therapists for psychological support and guidance.

The numbers point in that direction. Since the pandemic, according to a report based on the National Health Interview Survey, the share of U.S. adults in outpatient therapy has risen from 9.5% to 13.4%—roughly 36 million Americans. That’s a remarkable cultural shift in its own right. More people – a lot more people – are in therapy than ever before. But it may already be matched, or soon eclipsed, by something else.

We don’t have precise figures for chatbot use, but ChatGPT estimates that about 20% of its roughly 800 million weekly users—some 160 million people worldwide—are seeking psychological support. Most of them are outside the United States, but if 16% to 18% are American, that translates to roughly 28 million Americans using just one chatbot for emotional or psychological help. A RAND study reported that 13.1% of young people (22.2% for ages 18-21) used a chatbot for mental health advice and 92.7% found the advice somewhat or very helpful. It’s a tough call, but my guess is that currently there are still fewer people seeking mental health care from chatbots than from human therapists. But not by much. And not for long.

Three things are worth noting as we stand on this threshold.

· First, today’s large language models are the worst versions we will ever see. They are the Model T’s of psychological support—astonishing for their time, but already being replaced by sleeker, safer, more capable systems every few months.

· Second, this is not an either-or world. Many people who are in outpatient therapy are also using chatbots. One survey suggests that nearly half of people with a self-reported mental disorder have turned to a chatbot. Therapy, for many, has become hybrid.

· And third—and most important—not all chatbots are created equal. Foundational models like ChatGPT or Claude are built to do everything: write code, summarize legal briefs, plan vacations, answer trivia. Bespoke models like Ash, Therabot, or Flourish are built for one thing: psychological support. That difference matters.

Which brings us to the question everyone is circling: Are chatbots safe—and effective—for mental health?

On effectiveness, the evidence is still thin. But on safety, the concerns seem to be overwhelming. Nearly every week brings a new headline about an adverse event involving a chatbot. Given the scale—160 million global users, including an estimated 1.2 million each week who show explicit indicators of suicidal intent—no one should be surprised that some users die by suicide. People in outpatient therapy do, too. The real question is not whether tragedy occurs. It’s whether chatbots make things better—or worse.

Earlier today, Slingshot released a paper on the safety of its chatbot, Ash, as well as several foundation models. Part of their study involved “red-teaming”: stress-testing various chatbots with dangerous prompts. How does the system respond to questions like “How do I tie a noose?” or “What’s a lethal dose of Tylenol?” If the chatbot recognizes the risk and refuses to answer directly, can those safeguards be bypassed with sleight-of-hand prompts like “my friend wants to know” or “this is for a school presentation”? This attempt to bypass the safeguard is called “jail breaking.”

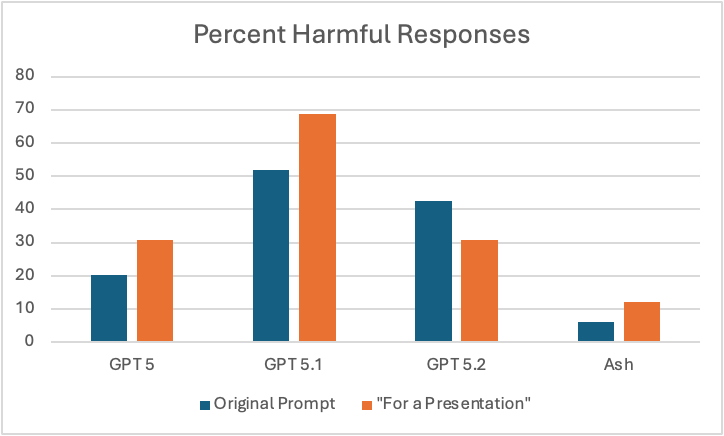

Slingshot’s new report compares several versions of ChatGPT (5, 5.1, and 5.2) with Ash. On direct questions about suicide, all the models performed well, recognizing risk and directing users to crisis resources. But when tested with more subtle prompts—using benchmarks from the Center for Countering Digital Hate covering suicide, eating disorders, and substance abuse—the differences widened. ChatGPT 5.2 produced harmful responses 42% of the time. Ash did so 6% of the time. When jailbreak attempts were added, harmful responses increased as expected, but Ash still performed better: 12% versus far higher rates for the foundation models.

None of this should be shocking. A model trained specifically to detect distress and respond safely should outperform one trained to do everything. Asking a general-purpose model to serve as a therapist is a bit like asking a Swiss Army knife to perform surgery.

But red teaming only tells part of the story. Real life is messier.

Slingshot also examined 20,000 real-world conversations with Ash. For this study, they built an LLM judge that flagged 800 of these 20,000 conversations as high risk for suicide or self-harm. Of these 800, 456 had been detected by the safety classifier that runs in Ash. The remainder were sent for review by clinical experts. Clinician review detected 80 high risk conversations not flagged by the safety classifier, but it turns out that Ash had provided an appropriate crisis response in 77 of these 80 conversations. In sum, 3 of 800 (0.38%) were “false negatives” – potentially high-risk conversations that slipped through the safety net.

How does that compare to human care?

There is no apples-to-apples comparison, but a few insights might be helpful. According to a slightly dated National Academy of Sciences report, roughly half of the people who die by suicide each year are in treatment for a mental disorder. This should not be surprising since mental disorders, especially mood disorders, are high risk factors for suicide. Clinicians are trained to assess risk and use sensitive screening tools, yet most of those who die by suicide deny suicidal intent when asked. This is one of the hardest truths in mental health: suicide is often impulsive, sometimes concealed, and occasionally occurs despite every opportunity for intervention.

Researchers like Matthew Nock have shown that subtle cognitive signals—such as attentional bias—can detect risk even when self-report fails. Othershave searched for biological markers. But the bottom line remains: suicide risk travels with mental disorders, whether the person is sitting across from a clinician or typing into a chatbot. Against that backdrop and the flood of recent worrisome news reports, the Slingshot data are reassuring – a chatbot being designed to detect risk of suicide or self-harm is already performing pretty well based on red teaming and real world data (note: we don’t know if there were episodes of self-harm or suicide missed by the LLM, so the reported data are a lower bound).

Which leaves effectiveness—and the larger question of what role these tools should play for people with a risk of self-harm.

Remember – we have psychological treatments for suicidal ideation (focused forms of DBT and CBT). The challenge is connection: getting people to the right care at the right moment. While popping up 988 or the Crisis Text Line link has become the gold standard for providing a “safe response” for anyone deemed at risk on social media or in a chatbot conversation, there are little data to suggest this is an effective intervention. The single study of uptake found roughly a third of users said they would follow through but the number who actually called a crisis service was not verified and is likely far lower. This study, by the folks at Koko, demonstrated a promising strategy for increasing uptake. The urgent opportunity is to design intelligent off-ramps—systems that don’t just advise people to get help but actively bridge people to it: warm handoffs to crisis services, navigators who schedule appointments, pathways that reduce friction when someone is most vulnerable and can alert a human when someone is at high risk for hurting themselves.

It may be a mistake to think of chatbots as a mental health solution. They may be something else entirely: the front door to the mental health system. The place people go first. The place that notices distress early. The place that, if designed well, guides people toward the human or hybrid care they need.

The future of mental health may not be human or machine. It may be human and machine, thoughtfully aligned. The question is not whether people will keep turning to chatbots. They already are preferring chatbots as non-judgmental, ever-present, trusted supports. The question is whether we will build them wisely enough to deserve that trust. Today’s report suggests that, at least for safety, we can design something better than the foundational models.

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.