Docile: Memoirs of a Not-So-Perfect Asian Girl

Hyeseung Song tackles head on the expectations she faced growing up and the journey she had to make to find her self-worth.

Writer Melissa Hung interviews artist Hyeseung Song about her recent memoir on mental health

The word “docile” only appears once in Hyeseung Song’s Docile: Memoirs of a Not-So-Perfect Asian Girl but its mention is pointed. From the bottom bunk of their twin beds, Song’s college roommate tells her, “You’re nothing like my docile Asian friend from boarding school.”

In naming her debut memoir after this cliché of Asian girls and women, Song tackles head on the expectations she faced growing up — from society’s stereotypes to her Korean immigrant parents’ ideas that she behave within certain bounds and advance to the Ivy League. Unflinchingly honest, Docile is at once a story about an eldest immigrant daughter, parental relationships, mental health struggles, and a journey Song must make in order to find her self-worth.

Docile recounts Song’s childhood in a white, affluent neighborhood in Houston. Her father’s get-rich-quick schemes and startup businesses drain the family financially while Song’s mother, an oncology nurse, resentfully provides stability. From the outside, Song conforms to the mold of the dutiful daughter and high achiever who excels academically, gets into Princeton, and attends Harvard Law School.

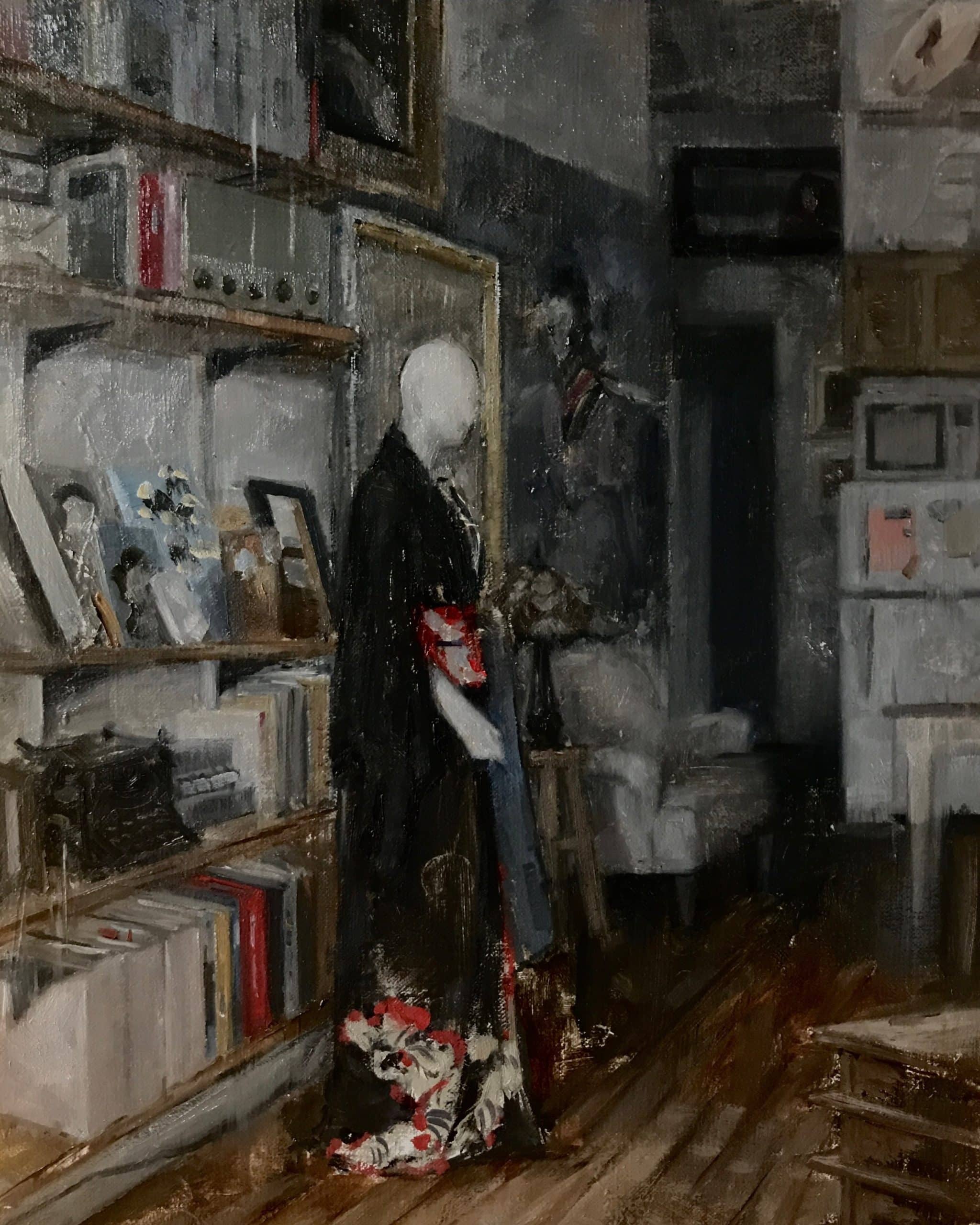

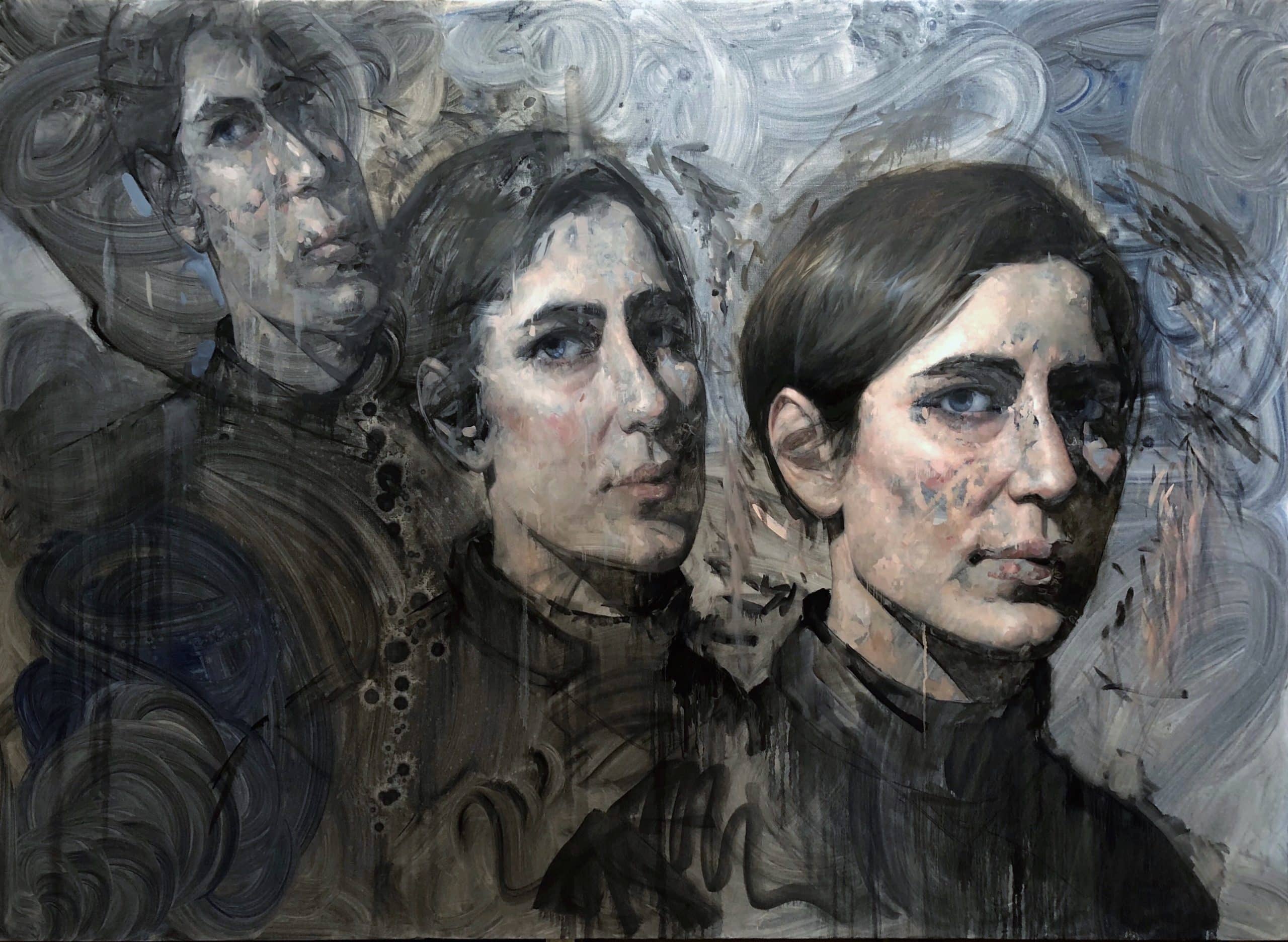

But throughout, she struggles with depression and mania, leading to a year-long leave of absence from college, suicide attempts, and two hospitalizations, the first of which leaves her with the wrong diagnosis. The more she lives for others, the more she erases herself. Song eventually decides to be true to herself and begins the work of healing to become the painter that she is today.

I recently spoke to Song over the phone. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

You are a visual artist, but you have written this memoir. How did you begin writing it? And did you know where it was going when you first started — that it was going to be about mental health and self-worth?

I just turned 46, and I started writing what were basically the first chapters of Docile when I was 20 or 21. I was writing in the creative writing workshops of my alma mater, Princeton, and I was basically just writing stories about my family, stories about the people that were the most maddening, the most annoying to me. [laughs] The people I knew who had obviously influenced much of my life, and yet I didn’t understand them. I was trying to understand them, but obviously it was in relation to myself. Like I was curious about my own life and how I had come to be.

And so I started writing what I thought was a story about immigration and growing up as a first generation Korean American in Texas with a colorful family. I didn’t know that I was writing a mental health memoir or a memoir about racial identity and identities outside the model minority myth. I didn’t know I was going to be an artist, but it really started with curiosity about my family and curiosity about myself.

Your memoir dovetails with the work of erin Khuê Ninh. She’s a scholar, a professor of Asian American studies and literature, who writes about how the model minority myth is not really a myth if people internalize it. I thought about that in the scene where you’re in the dean’s office and you say to her, “I’m a first generation Korean American. I don’t ever have a choice but to succeed.” She also writes about the immigrant nuclear family as a form of capitalist enterprise. Do these ideas resonate?

I feel like the model minority myth is like the American dream for Asian Americans, right? It’s their own version of how you can succeed in America, but it’s a construct based on scarcity. It’s a construct of “there can only be one Asian person in a mixed group.” Otherwise we completely disappear. It’s this idea that if all Asian Americans are docile, STEM-excelling tryhards, you can be counted on to maintain the status quo. The model minority myth makes you feel like you have to do the right things and be the right things — be model — in order for you to earn visibility and legitimacy in your country and in order to deserve basic things like food, shelter, dignity, love.

And the answer to anything that’s in a capitalistic construct like scarcity is abundance, right? The idea that you can get whatever you need and there’s no limit. But it’s actually not! The answer to anything like the model minority myth — and I say this in my book — is not abundance, it’s actually enoughness. It’s this idea that whatever you do and whatever you do not do, the answer is always the same. You are enough. You’re just here and you are enough, no matter what you do. You deserve everything. You deserve food, shelter, water, love, dignity based on your enoughness because you’re human, not because of the things that you do and the ways that you are.

You were not diagnosed properly with bipolar disorder until you were 35. Ten years prior to that, you were given a diagnosis of dysthymia, mild depression, which seemed to lead to a lot of self-blame. Do you think the correct diagnosis earlier would have changed things for you?

Yes, I do. I think that working within a Western therapeutic construct takes certain education and skills from the patient. Based on my own experiential existence and my experiences in these environments, you go in and you are expected to be able to discuss your symptoms. And I think there’s also an expectation looking at me — I was a Harvard student — the expectation is that I would be very articulate about my symptoms. And so when I wasn’t particularly articulate, it was like the model minority myth bullshit bias was already entering into that therapeutic realm, and they were making assumptions about me. And I 100% believe that the care that was shown me at McLean, the first psychiatric hospital, was not culturally competent care.

In the end the psychiatrist who helped me in the second hospitalization, she was an immigrant herself. She was relaying culturally competent care. She wanted my opinion about it, too. She was showing me the DSM and asking, “Does this sound right to you?” And it was, for me, a Matrix-like moment. It was explaining so many different things in my life that I didn’t even realize were part of the mental health picture. Things like me not sleeping or working really hard at certain times, like seasonally having a lot more energy in the fall, which is still true today. I am just much faster in the fall, very slow in the summer. There’s a lot of seasonal affective aspect to bipolar. That’s very clear to me. But I think that she was really smart, this psychiatrist, because she was wanting to check in with me and say, “Hey, does this actually jive with your own experience?” And it really did.

How do you feel that bipolar disorder is intertwined with the pressure to succeed that you were also facing? Or is it not?

I think it is. I think with this diagnosis, it’s so clearly a diagnosis that someone like me, this high-achieving Asian American female who looks the way I do — it’s not consonant with how I appear, right? But that’s the whole thing. All of us have things that are inconsonant with how we appear, especially because Asian Americans are dealing with such a rigid idea of themselves anyways, whether we internalize it or if it’s externalized in the culture. I’m not a mathematician. I’m not an engineer. I’m an artist. I have this bipolar disorder diagnosis that I deal with every day. There’s something that is more to me than meets the eye here with this person — and that’s true for all of us.

You were in law school, but you didn’t really want to be. So your compromise was, “I will also study philosophy.” That logic comes from the mind of someone who’s so entrenched in the model minority construct. How did you overcome that to embrace the visual art that you wanted to do?

One of the reasons I wanted the book to feel very propulsive is because my whole experience of searching was very propulsive. I was like, “I’m going to be a philosophy student. I’m going to learn how to synthesize things so that I can understand how to live in this world.” It sounds like such a 21-year-old thing to do. I’m going to learn from the classroom how to live outside the classroom, right? And I 100% was trying to do this. There’s part of me that thought, “Well, philosophy grad school will be easier than 1L Year at Harvard Law School. I’m going to do this, and then maybe I’ll do some art on the side.”

But then graduate school at Harvard was 10 times as stressful as law school was. So I was there, and then I get sick, right? And when I’m in the hospital, I realize, all of these breadcrumbs had been sprinkled out for me. I knew that I was on the wrong track. Intuitively, I knew. But my mom had spent her whole life telling me my intuition was wrong, so I had not honed that as an adult, and did not trust that. And then I end up in the hospital.

The answer to anything like the model minority myth is not abundance, it’s actually enoughness. You are enough. You deserve food, shelter, water, love, dignity based on your enoughness because you’re human, not because of the things that you do and the ways that you are.

Hyeseung Song

And I realized, “I have to have a reckoning for myself. I have to choose to heal myself.” My mom and dad had lost so much of their power because I realized I had almost died. And back then, my ex-husband, who was my boyfriend at the time, his compass was always due north. He always understood where he needed to be, what he needed to be doing, and he gave me a lot of strength. He supported me in ways that my parents did not. They were too limited at that time in life. I mean, they loved me, but they were not going to unconditionally accept the things that I wanted to do in life.

What are your hopes for this book in terms of who reads it or how it goes out into the world?

Five or six months ago, I would have told you all of these wish list hopes. In my heart of hearts, it would be amazing if it were a best seller or became a movie or something like that. But that’s not really what I’m interested in anymore. I think a lot about the event that you moderated with Grace Loh Prasad, the author of The Translator’s Daughter, and my friend Emmeline Chang’s question to Grace about how it feels to write a book about having no community or no home, and then have it go out in the world and through that book create the community and home you always longed for.

And I think a lot about this particular statistic: that the number one cause of death for young AAPI adults ages 15 to 24 is suicide. I feel that I’ve been so lucky in my life. Every room I’ve gone into, there have been people who looked out for me. In Docile, I go to a lot of places. I go to Korea. I go to Princeton. I go to Houston. I go to Cambridge. But wherever I am, someone is looking out for me. There’s no reason for anyone to look out for me, and yet someone always stepped in and that’s why I’m alive now.

And if we have this epidemic of AAPI suicides for young adults someone has to step in. And if there’s not someone in the room to help you — I know this sounds very hubristic, but it comes from this place of hope — I hope, I wish, I want Docile to be there for someone who can read it and be like, “Oh, this is the person who’s going to help me in the room. This story can help me. I don’t have to do the thing that I’m trying to do.” Because this this happens all the time still.

The name “MindSite News” is used with the express permission of Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person workshops in the field of mental health and wellbeing. MindSite News and Mindsight Institute are separate, unaffiliated entities that are aligned in making science accessible and promoting mental health globally.